-

Blog Post Sustainable timber engineering: A structural solution for the UK’s life sciences sector

-

Published Article Moving forward together: A new era beckons the UK water sector

-

Blog Post Bringing social value to the grid: A roundtable on transmission and distribution

-

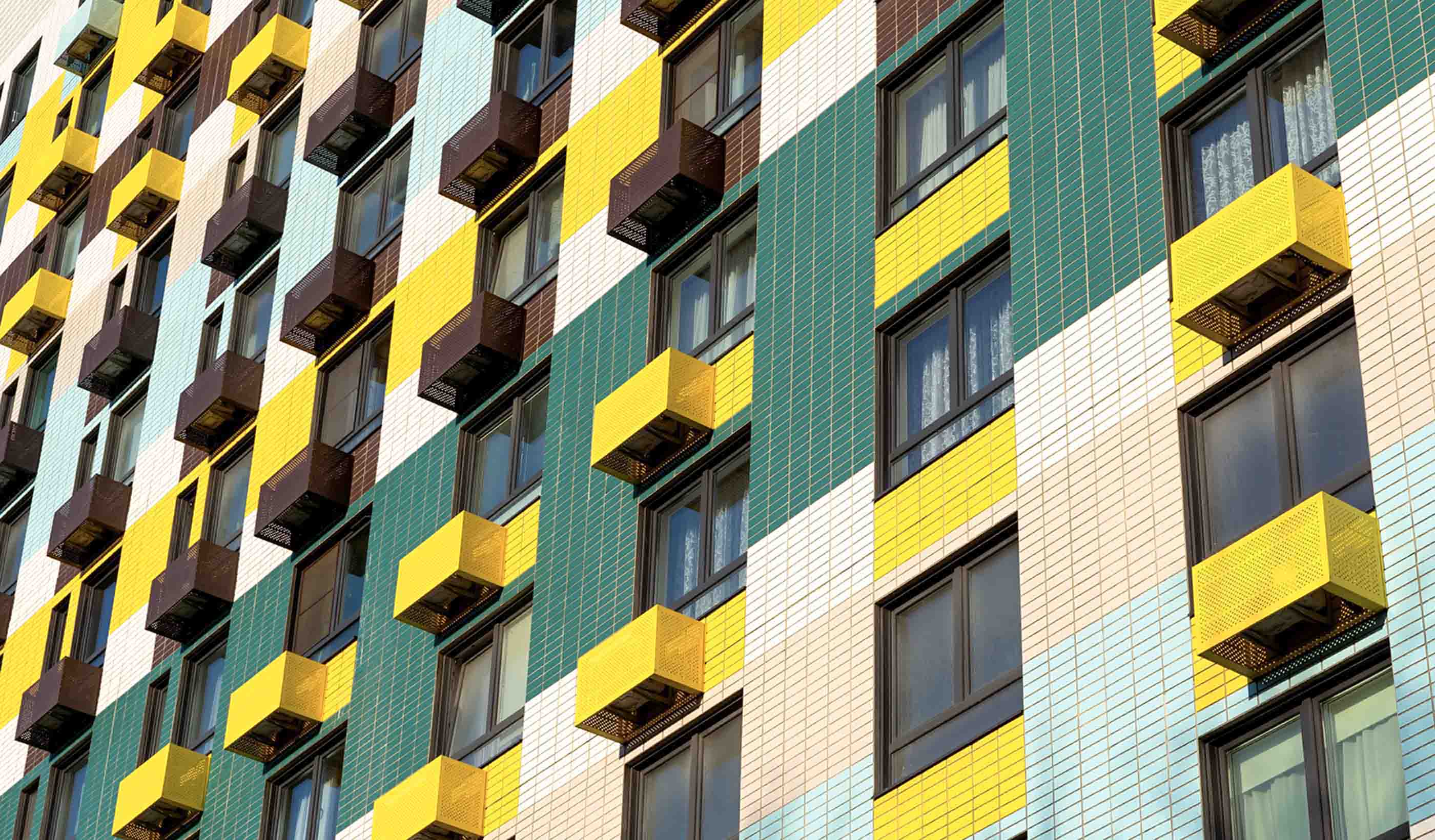

Blog Post What are the steps for designing new communities in England?

Ideas

Explore the trends, innovations, and challenges impacting the built and natural environments.

All Ideas

-

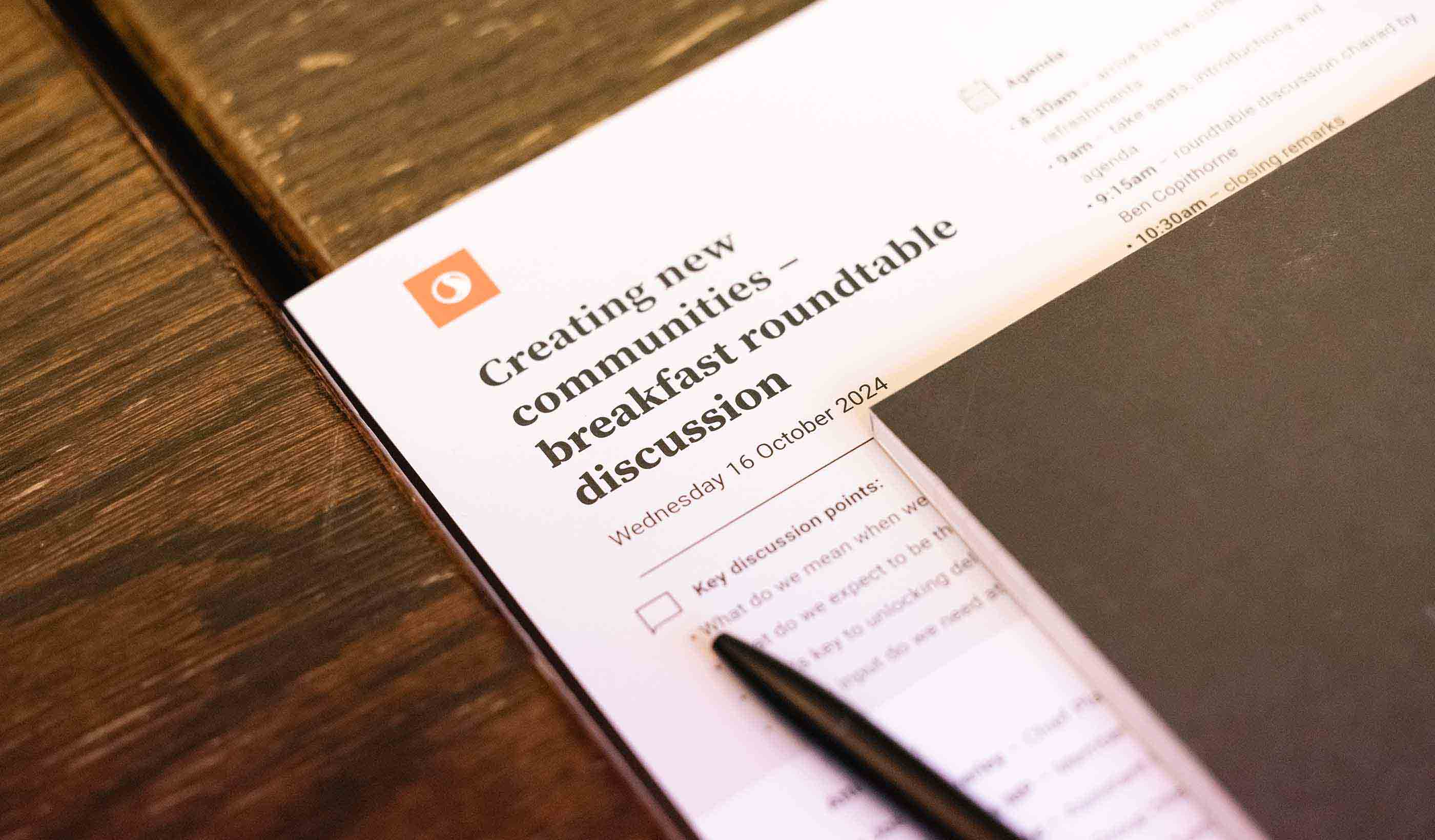

Blog Post Insight-led thinking: Bringing the industry together to deliver new towns in England

-

Report New towns: Creating communities, building trust, realising the opportunity

-

Published Article Moving forward together: A new era beckons the UK water sector

-

Publication Power Pulse October 2025 │ Progress towards Clean Power 2030

-

Video Building Dubai’s first integrated cancer hospital using Autodesk Forma

-

Video Shaping a cleaner future through better air quality monitoring

-

Blog Post Renewable energy is key to building the most sustainable data centres

-

Blog Post Sustainable timber engineering: A structural solution for the UK’s life sciences sector

-

Blog Post Bringing social value to the grid: A roundtable on transmission and distribution

-

Blog Post Data centre power: Using the gas network and hydrogen to power data centres

-

Blog Post Roundtable: Data centre design, power, and the growing need for public engagement

-

Podcast The SCOPE: Designing sustainable data centres

-

Podcast The SCOPE: Powering the UK’s data centres—the need for new ideas

-

Blog Post What are the steps for designing new communities in England?

-

Podcast The SCOPE: Data centres and net zero communities

-

Blog Post 3 ways material choices can improve data centre construction and reduce carbon

-

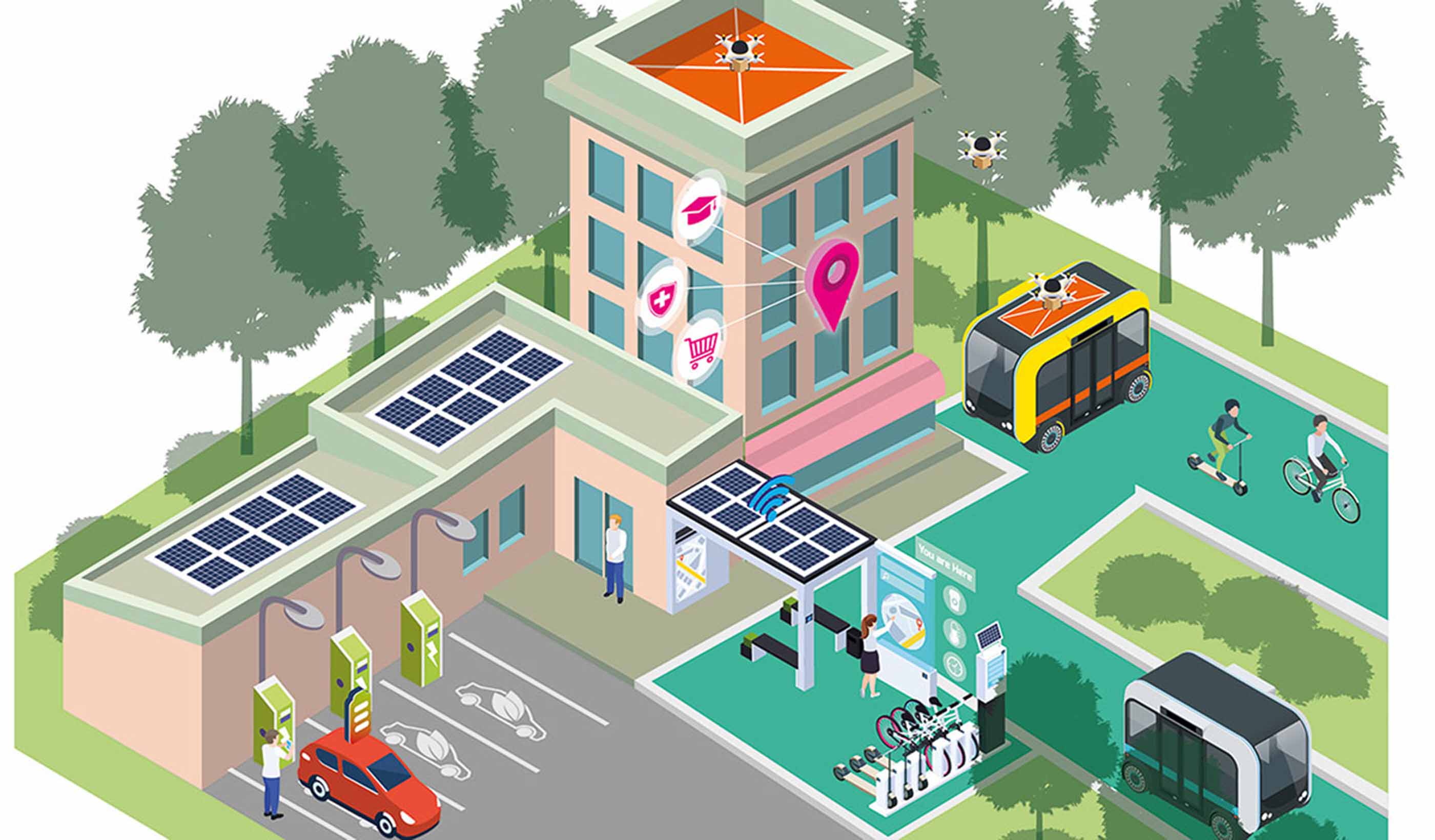

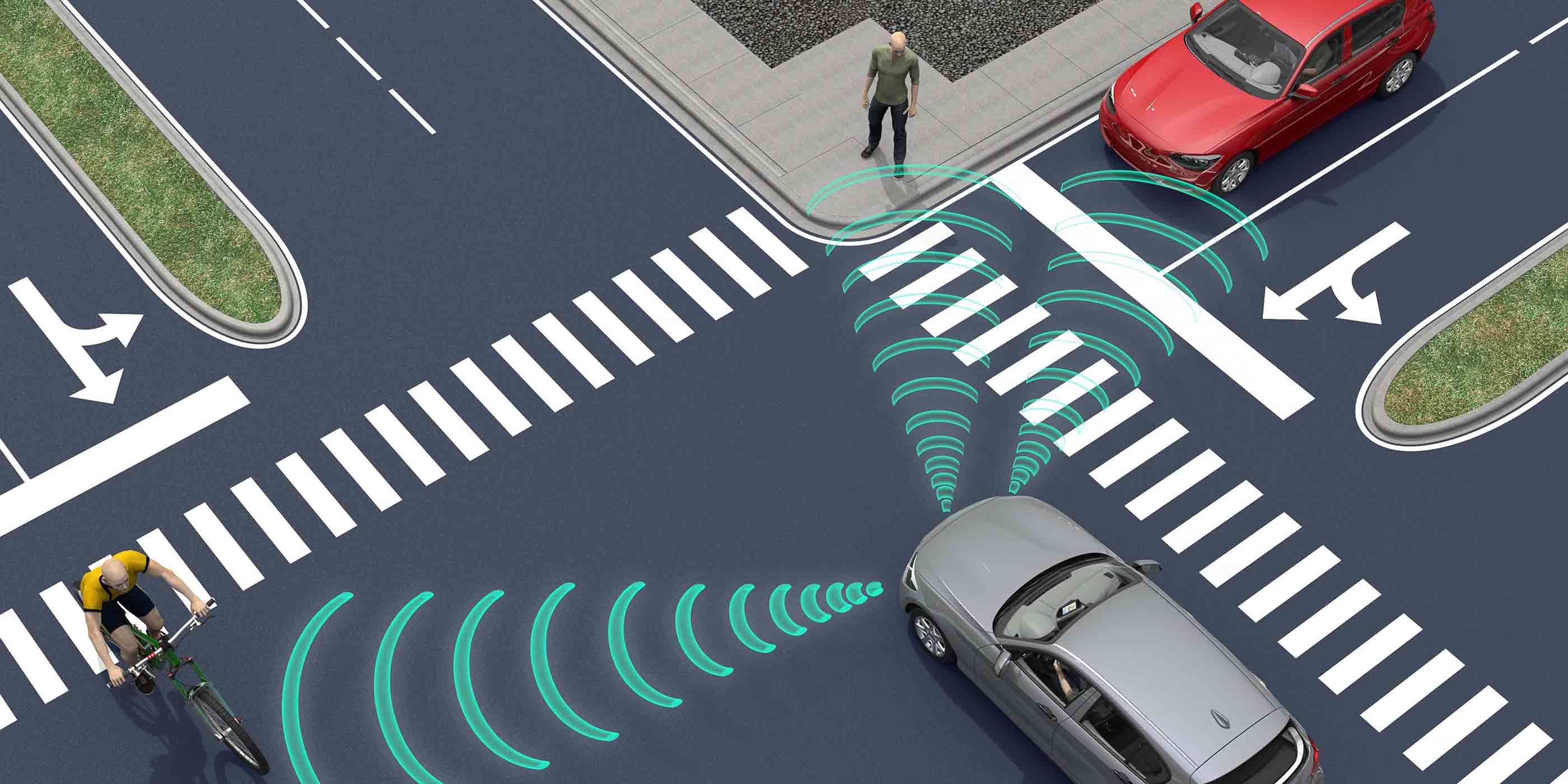

Blog Post Interchange: How transforming transport will drive growth and better UK mobility

-

Blog Post Adapting to climate change: An evidence-based approach to the built environment

-

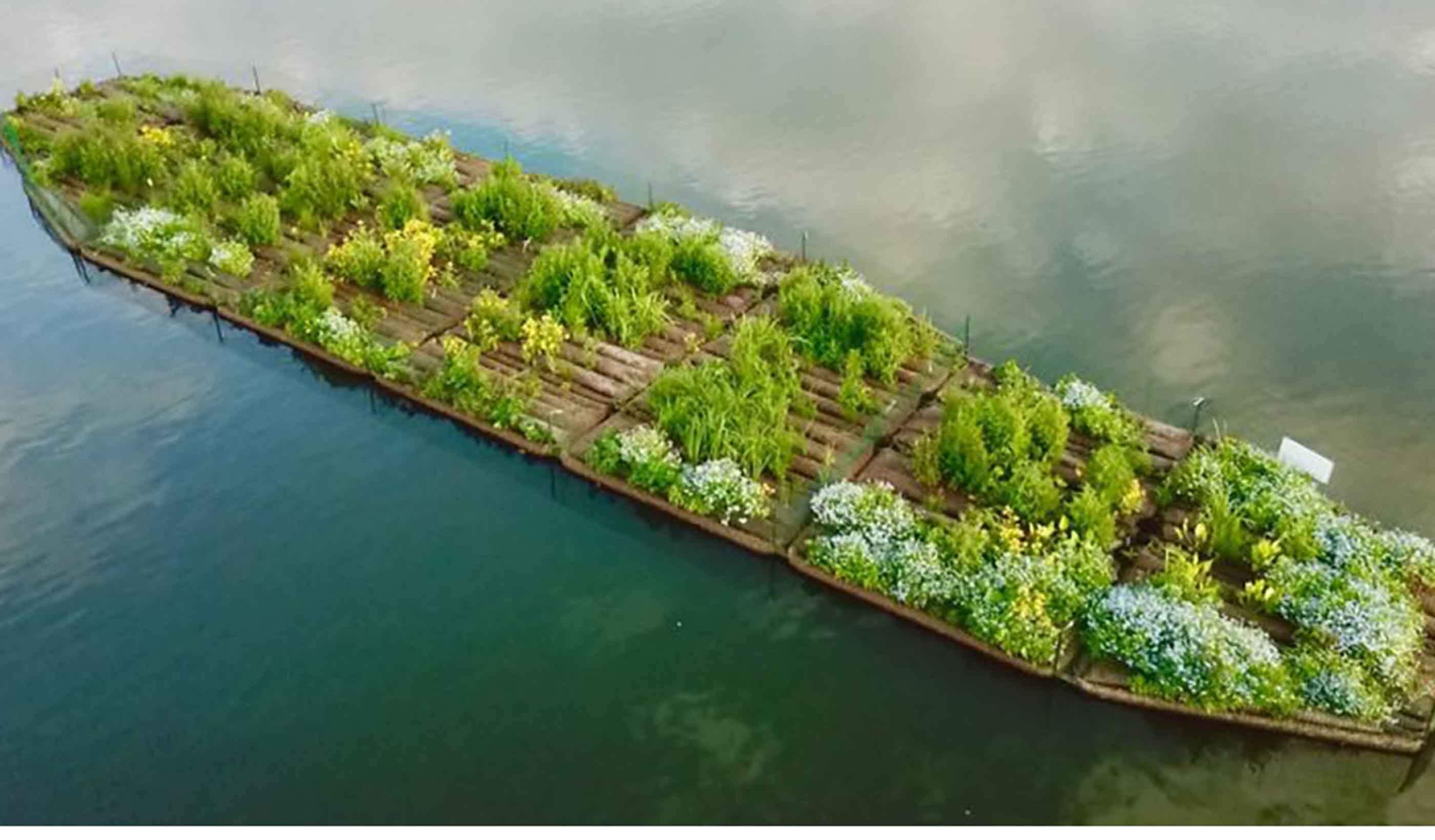

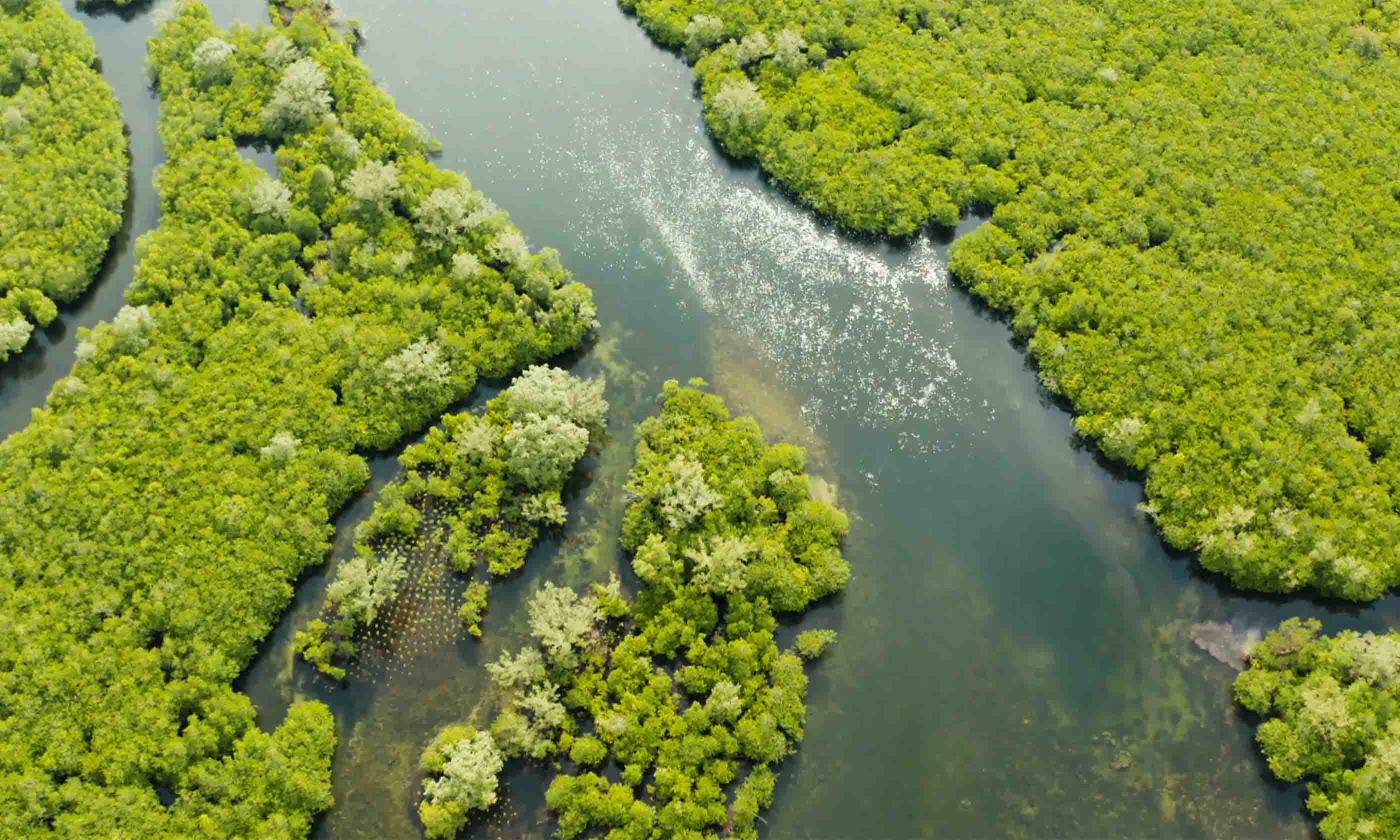

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The impact of nature-based solutions in design and engineering

-

Podcast The SCOPE: Smart grids—what are they?

-

Blog Post Roundtable: Time for momentum on ambitious local plan making

-

Podcast The SCOPE: Understanding the Building Safety Act

-

Blog Post How to achieve balance with compulsory purchase orders

-

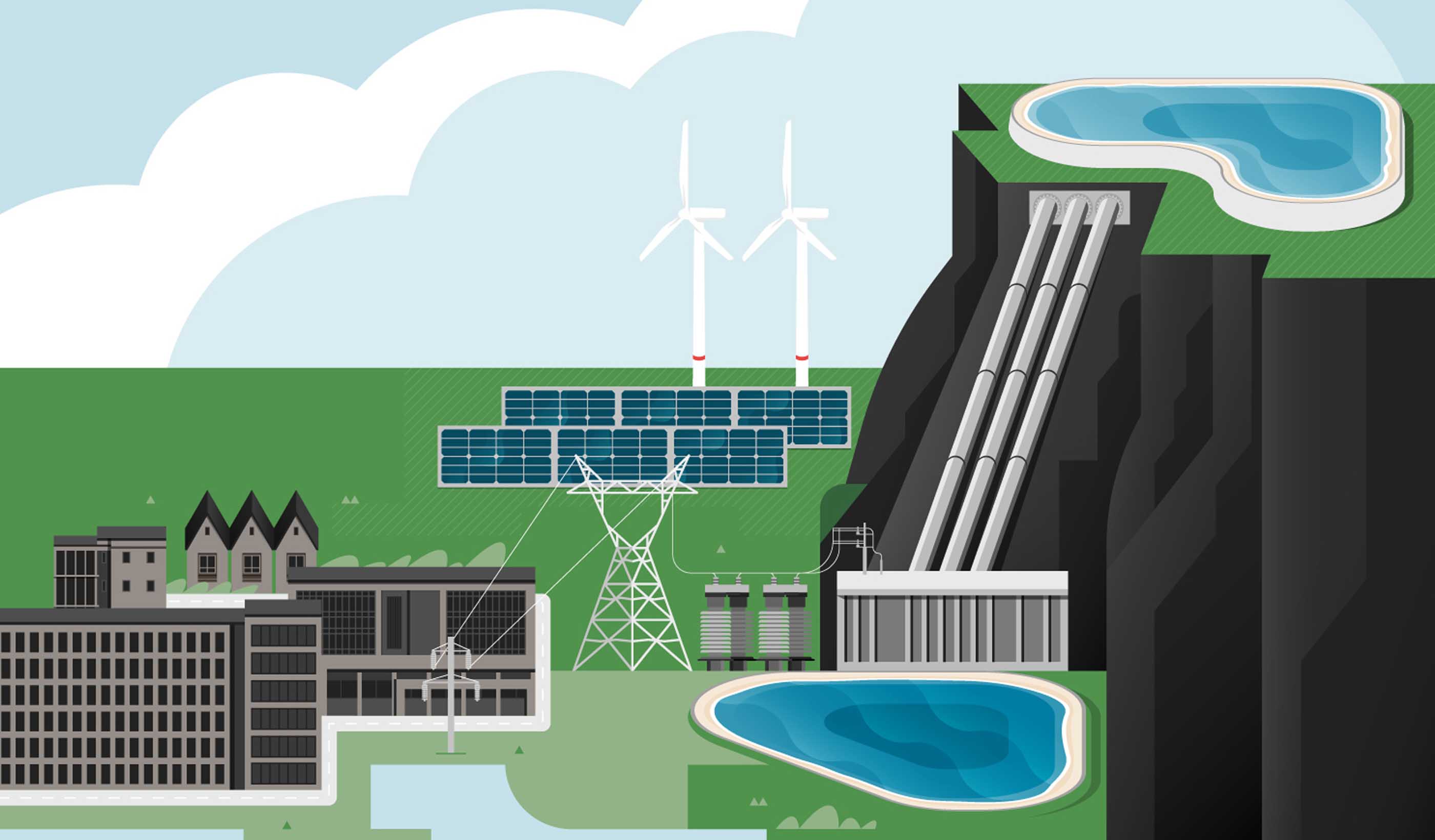

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: How pumped storage hydropower can help the global energy transition

-

Podcast The SCOPE: Culture change and the Building Safety Act

-

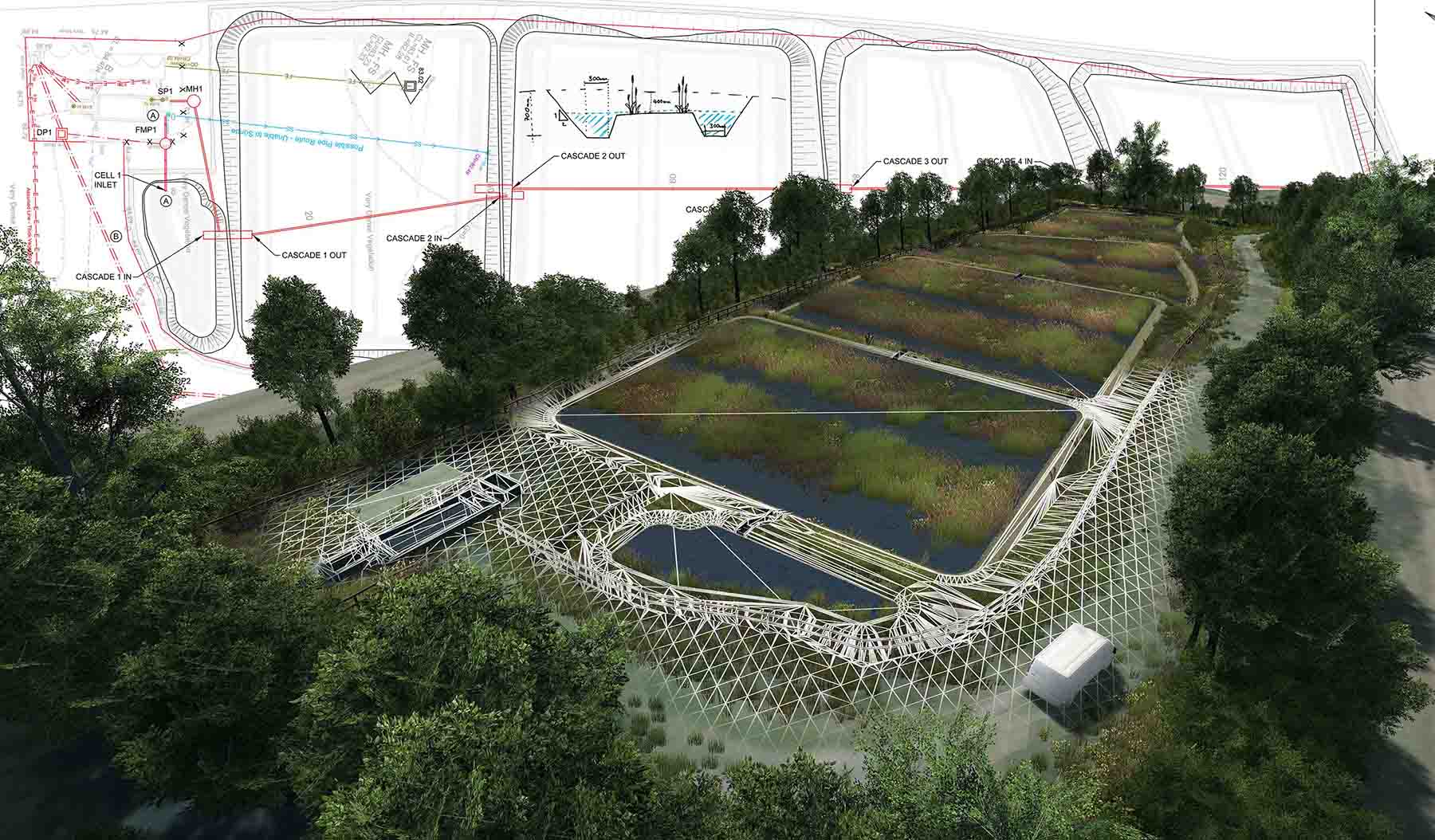

Published Article Integrated catchment systems: A paradigm shift in sustainable management

-

Podcast The SCOPE: Competence and the Building Safety Act

-

Stantec’s response to Invest 2035: the UK’s modern industrial strategy

-

Blog Post Vision and Validate: Time for a shift in transport planning?

-

Video The impossible fix: Engineering under London

-

Blog Post Roundtable: 5 starting points for new community planning

-

Blog Post How to use energy grid queue management reforms to get connected

-

Blog Post Supporting better kerbside management for last-mile logistics

-

Published Article Sustaining water supplies across the UK

-

Blog Post The new NPPF: Progress, potential pitfalls, and solutions

-

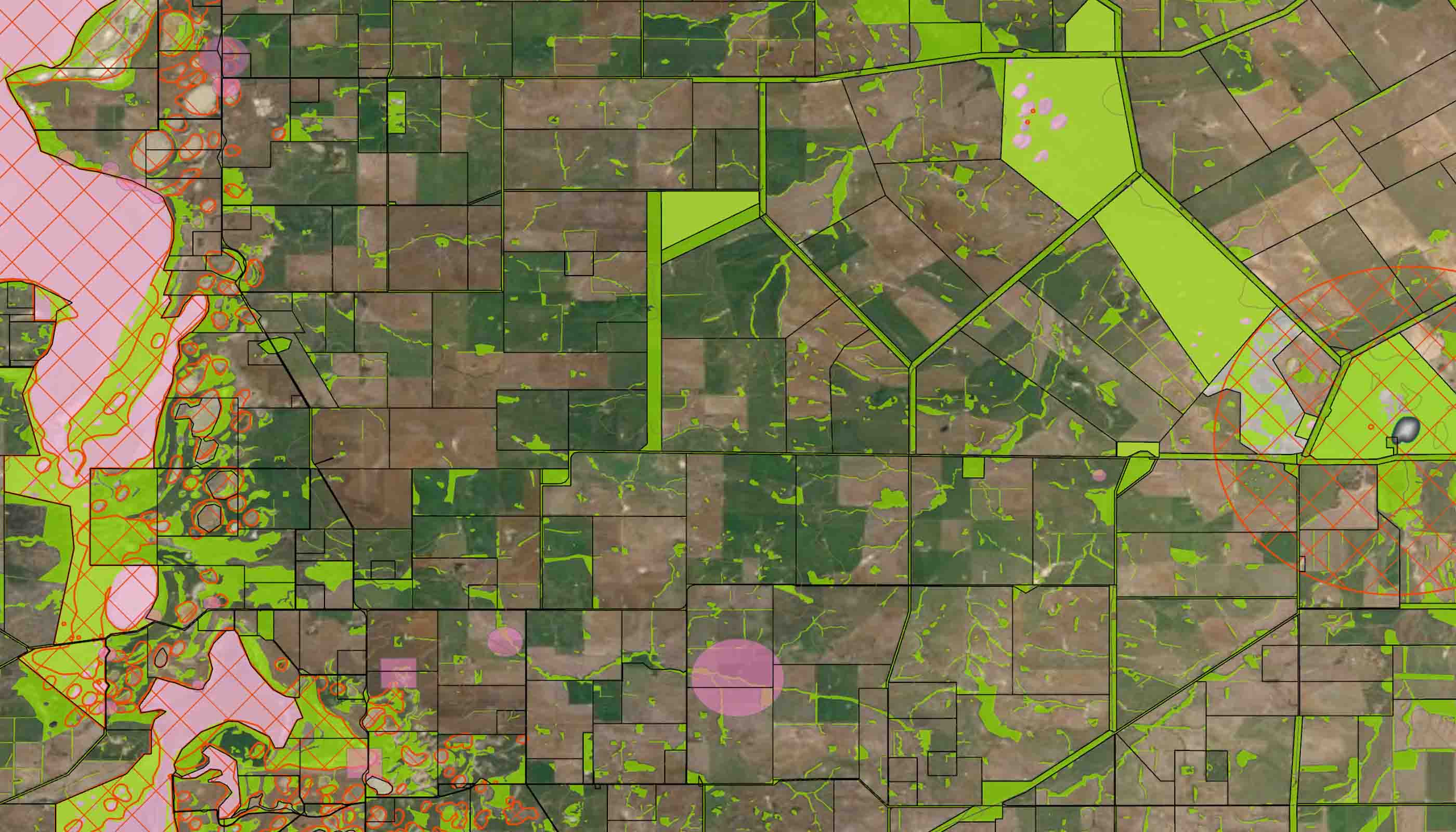

Published Article Huge increase in private sector investment is essential to address the biodiversity crisis

-

Report An analysis of England’s local housing needs by Stantec’s Development Economics team

-

Blog Post 4 considerations for your next grid-modernisation project

-

Report Later living: A blueprint for planning to deliver homes for older people

-

Blog Post Transforming delivery of anaerobic digestion in the United Kingdom

-

Video With every community, Stantec redefines what’s possible

-

Blog Post 10 things to know about the future of hydrogen development in the UK

-

Report Understanding migration from London to the wider South East of England

-

Blog Post A new life for waste: Advancing a circular economy

-

Blog Post 6 ways we can refocus efforts to drive regeneration

-

Video Nature-based solutions: Using engineering and nature to solve environmental challenges

-

Blog Post BNG is just the start. We need to break down silos to create a better tomorrow

-

Report Funding regeneration: An art or a science?

-

Published Article Getting back to nature

-

Blog Post How integrated thinking can help boost the energy transition

-

Blog Post Challenges and opportunities in the UK’s race to net zero mobility

-

Blog Post Small modular reactors in the UK: Driving energy security with nuclear power

-

Podcast The SCOPE: Bridging the Gap

-

Report Biodiversity Net Gain: What does this new legislation mean for you?

-

Publication Inside SCOPE at COP28

-

Report A solution for meeting housing needs across London and the wider South East

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The Rail Episode

-

Report Showcasing success with Nature-based Solutions at COP28

-

Blog Post Bridging tomorrow’s net zero mobility gap

-

Report Getting to grips with mandatory SuDS

-

Blog Post Can urban density solve our equity, economic, and sustainability woes?

-

Video How is Stantec making an impact?

-

Published Article Got yourself a deal? M&A lessons from Stantec

-

Published Article PAS 2080: Moving from trade-offs to sustainable synergies in the UK water sector

-

Video What is Stantec.io?

-

Technical Paper Advancing debris flow hazard and risk assessments with modeling and rainfall intensity data

-

Technical Paper What does landslide triggering rainfall mean?

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: Extreme Weather and Digital Solutions

-

Blog Post Driving behavioural change and delivering a modal shift in mobility

-

Published Article Building trust in water recycling

-

Published Article Nature-based solutions: Crucial innovations for a resilient, sustainable future

-

Blog Post How to create a digital golden thread for existing buildings

-

Blog Post PAS 2080: Hitting the right net zero notes, time after time

-

Video How to repeatedly save your client time and money with Stantec Beacon

-

Published Article From A to Gen Z: Designing better workspaces for everyone

-

Blog Post Delivering and demystifying social value

-

Blog Post A two-tier system? We must embrace the digital golden thread across the built environment

-

Blog Post Keeping the wheels on the bus moving for a successful post-pandemic journey

-

Report Better Places for a Better Quality of Life

-

Blog Post Building Safety Act’s second staircase: Is it the easy way out?

-

Published Article The cost of delaying water resilience efforts is too high

-

Blog Post 6 design approaches that humanise cancer care amid technology advances

-

Published Article How to curb skepticism around Nature-based Solutions

-

Blog Post Designing for neurodiversity: Creating spaces that are inclusive of all

-

Blog Post Reducing road rage on streets through better design

-

Blog Post Water and energy: A symbiotic relationship

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The Smart Cities Episode

-

Published Article Net Positive Energy for People

-

Blog Post Give inclusivity a sporting chance by designing better recreational spaces

-

Published Article The challenges of managing long-term water assets

-

Published Article The challenges and opportunities of nature-based solutions

-

Publication Inside SCOPE Issue 2: Week 2 at COP27

-

Publication Inside SCOPE Issue 1: Week 1 at COP27

-

Blog Post Everything is connected: digital partnership opportunities for infrastructure and water

-

Blog Post Understanding the constant evolution of transport planning

-

Video Cascading Climate Events and Predictions: Virtual Weather and Debris Flows

-

Blog Post Supply and demand: Energy security in the UK

-

Published Article Storm Overflows: Mission Impossible?

-

Published Article Cleaner energy from waste

-

Video Intro to FAMS: How it works

-

Video Intro to FAMS: Built for users

-

Video FAMS or FAMS Pro - Choose FAMS

-

Video FAMS or FAMS Pro - Choose FAMS Pro

-

Podcast How retail and office spaces are being transformed in the post pandemic world

-

Technical Paper A comparison of two runout programs for debris flow assessment at the Solalex-Anzeindaz region of Switzerland

-

Blog Post Welcome to the carbon culture club

-

Report Delivering better place outcomes through use of data

-

Webinar Recording Natural Capital for AMP8

-

Video Our approach: The Climate Solutions Wheel

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The CommunityHQ Episode

-

Published Article Scaling up UK energy storage is vital to securing supply and stabilising the grid

-

Published Article Involve comms teams at earliest stages of any projects

-

Blog Post How can businesses and policy makers achieve climate justice?

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The EnviroExplore Episode

-

Blog Post Data + Design = Decision

-

Blog Post The future is electric: supporting Blackpool’s new bus fleet

-

Blog Post Hydro batteries: Making renewables dispatchable

-

Blog Post How can solar canopies help us electrify our industry?

-

Blog Post Making smart asset choices from imperfect asset data

-

Published Article The social dimension of transport planning

-

Blog Post Regenerative urban greening in the face of a hotter, wetter UK

-

Webinar Recording Developer Masterclass Webinar Series: Brownfield Land

-

White Paper Bridging the Gap programme of research

-

Blog Post Groundwater plays a critical role in climate change adaptation

-

Published Article UK water industry must prepare for riverine bathing water designations

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The Fire Flow Episode

-

Webinar Recording Catchment Systems Solutions

-

Blog Post Smart resilience planning and design includes triple bottom line benefits

-

Blog Post Breaking the bias: How two women are making spaces and places more inclusive

-

White Paper The Geography of Hydrogen is the catalyst to economic stimulus and adaptation to climate change

-

Blog Post What is design automation, and how can you optimize it for your next project?

-

Webinar Recording Climate Solutions Webinar Series: Navigating climate change terminology

-

Published Article Changing how we manage our water assets

-

Published Article Mining towards Renewable Energy in the UK

-

Published Article Breaking the model: designing streets for the future in Suffolk, UK

-

Video GlobeWatch: World Leading Remote Sensing Technology

-

Published Article Delivering pumped hydro storage in the UK after a three-decade interlude

-

Blog Post How is transit responding to reopening?

-

Blog Post Best places to produce hydrogen? Look at a topographic map

-

Blog Post Climate emergency: How governments around the globe are tackling the crisis

-

Blog Post Cleaning up our waters: actions to remove nitrogen pollution from estuaries and coasts

-

Blog Post How will Nutrient Management Plans affect UK growth objectives?

-

Blog Post Beneath every new development is nature we need to protect

-

Webinar Recording STWL WINEP phosphorus obligations - Opportunity for nature based solutions

-

Blog Post To incentivise or to tax, or both? How we can reduce carbon in our infrastructure schemes

-

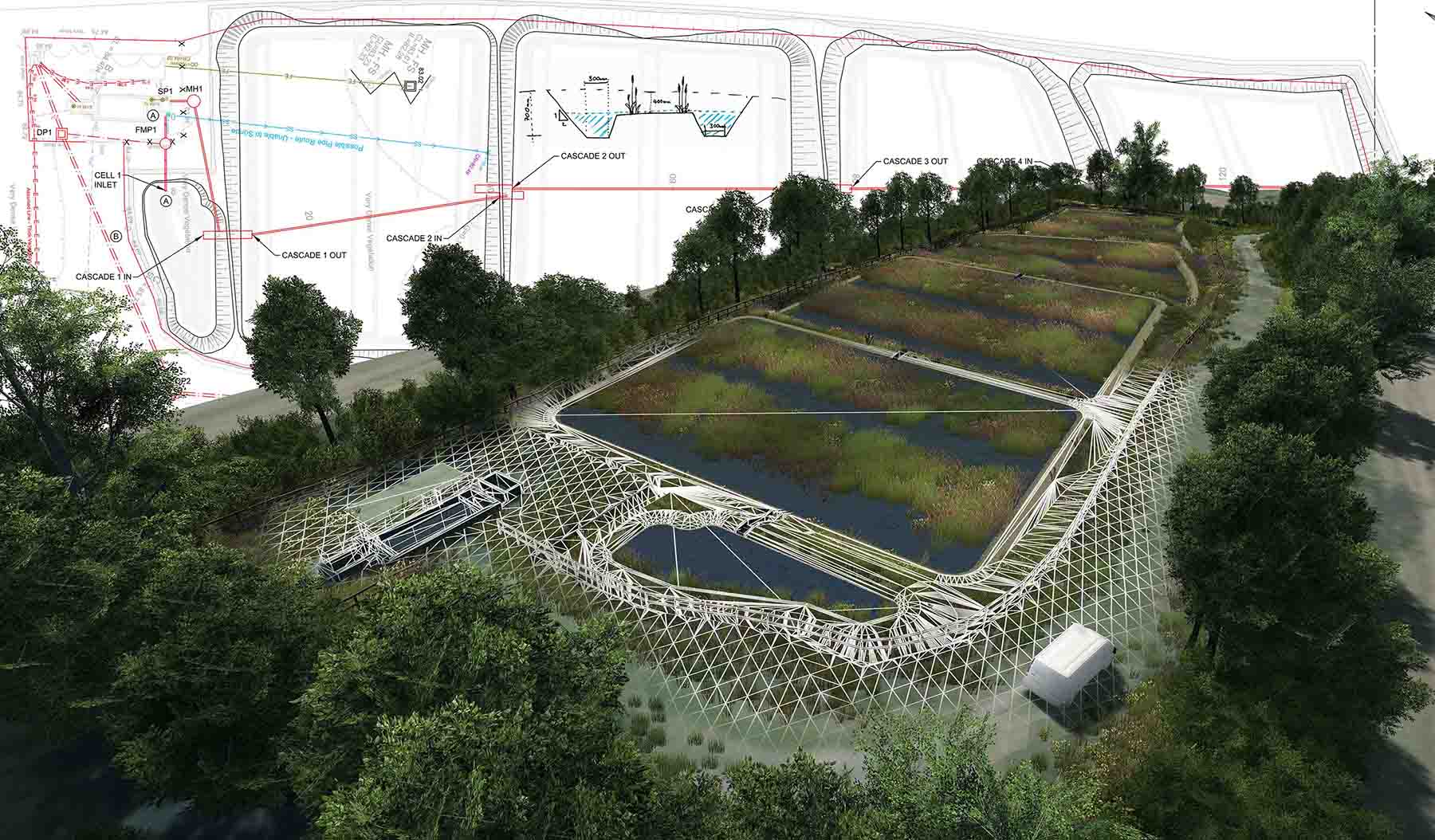

Published Article Integrated Constructed Wetlands: The Start of a Journey

-

Blog Post Passports to a net zero carbon future

-

Published Article Waste-to-energy tech could slash carbon emissions, but its promise remains underdeveloped

-

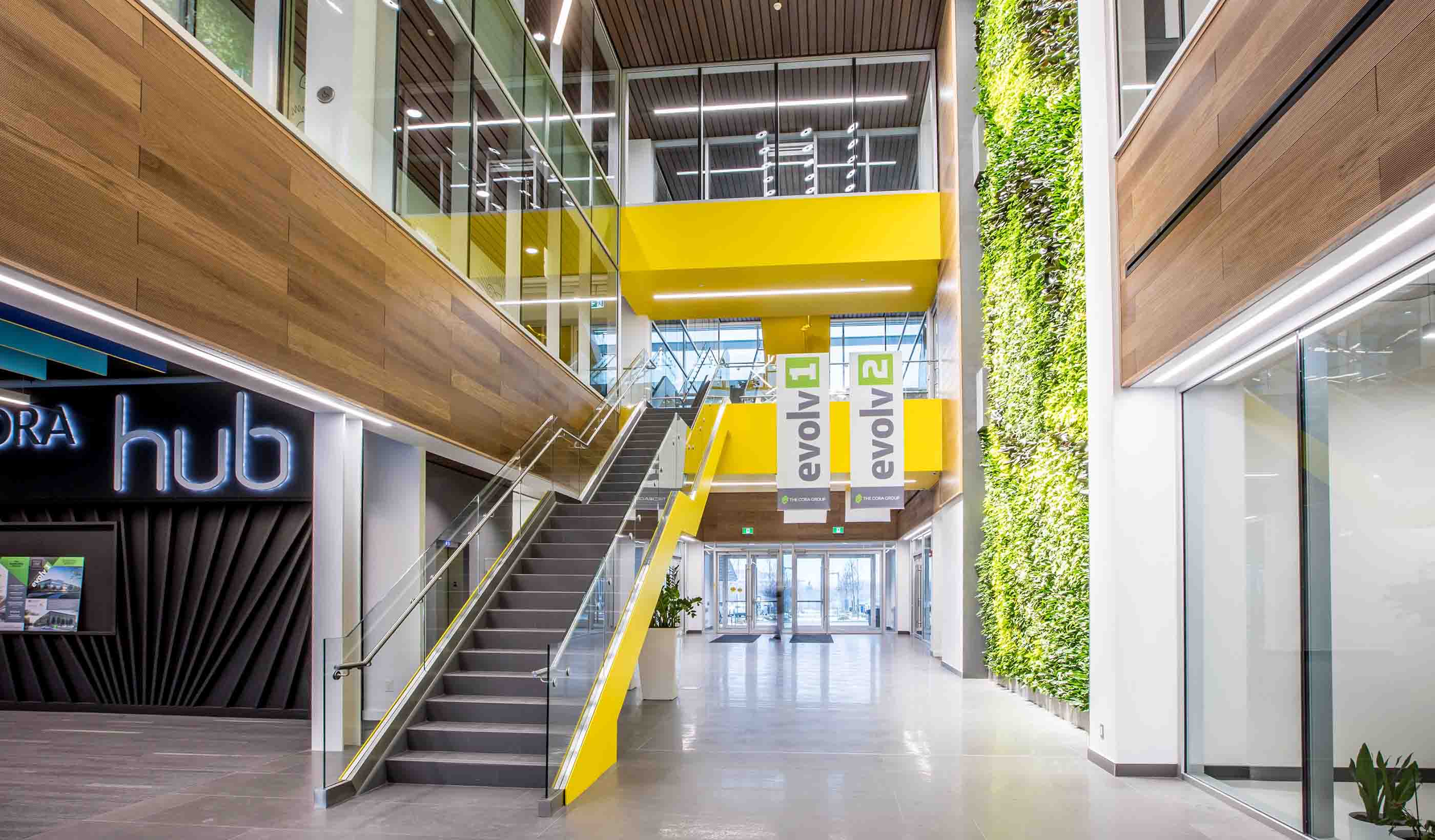

Blog Post Evolution – How a systems based approach to asset management is realising new benefits

-

Blog Post Reducing carbon on UK’s road schemes: actions to take for the sake of climate change

-

Published Article Applying a carbon lens in evaluating strategic water resource options

-

Blog Post What does connectivity look like for your community?

-

Published Article Developing strategic resource options to tackle increasing water stress

-

Presentation Producing Hydrogen using Hydropower in the US

-

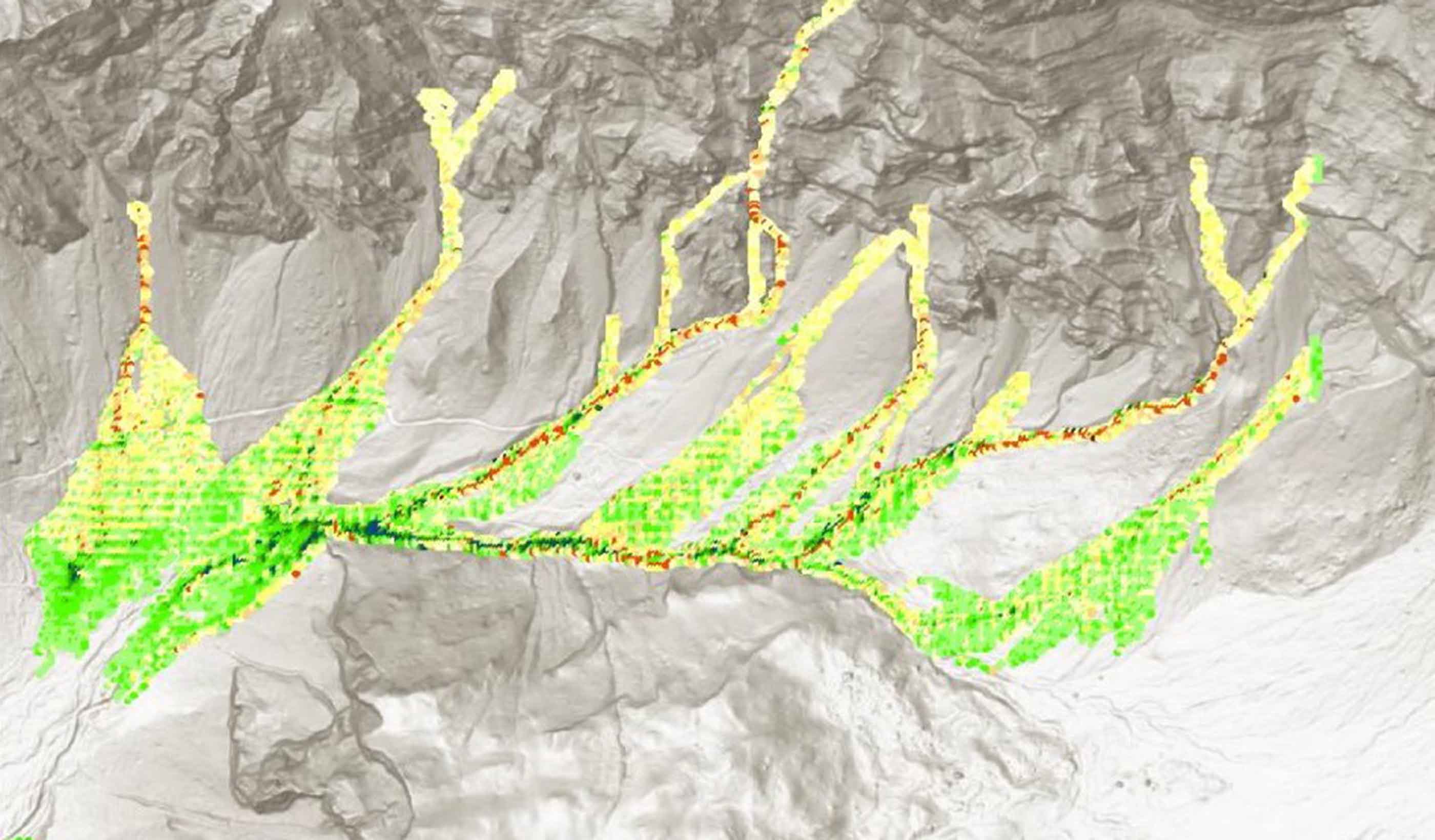

Blog Post A new digital tool can help predict landslides, protecting people and infrastructure

-

Report Shaping the future transport network for the Thames Valley

-

Blog Post Can your council lend a hand to small businesses?

-

Podcast We need an EV charging renaissance

-

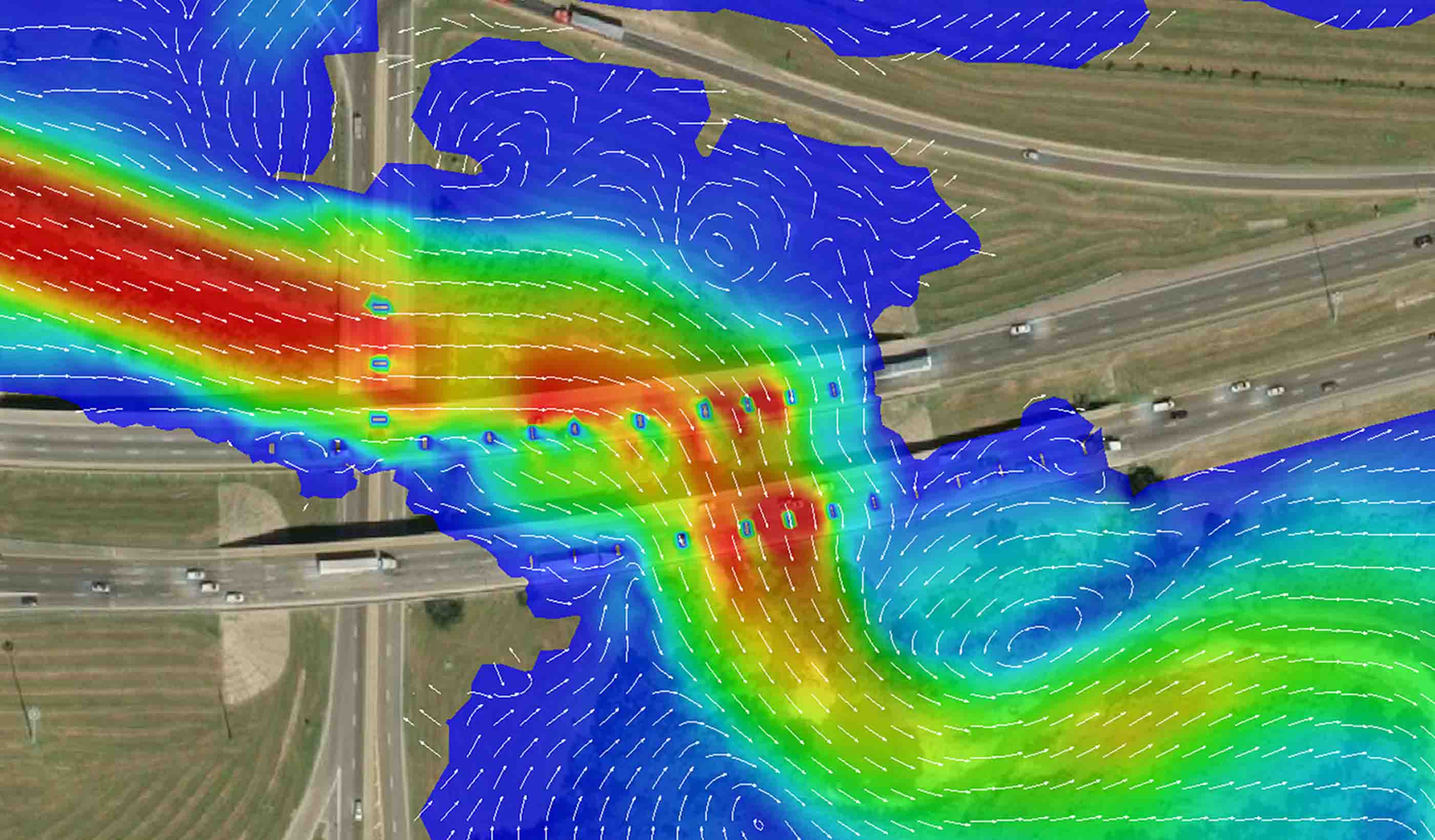

Blog Post Completing the picture: The future of hydraulic modeling is two dimensional

-

Published Article What's the outlook for planning and regeneration in Reading?

-

Blog Post 7 trends and techs—and 3 obstacles—shaping the big picture for an energy transition

-

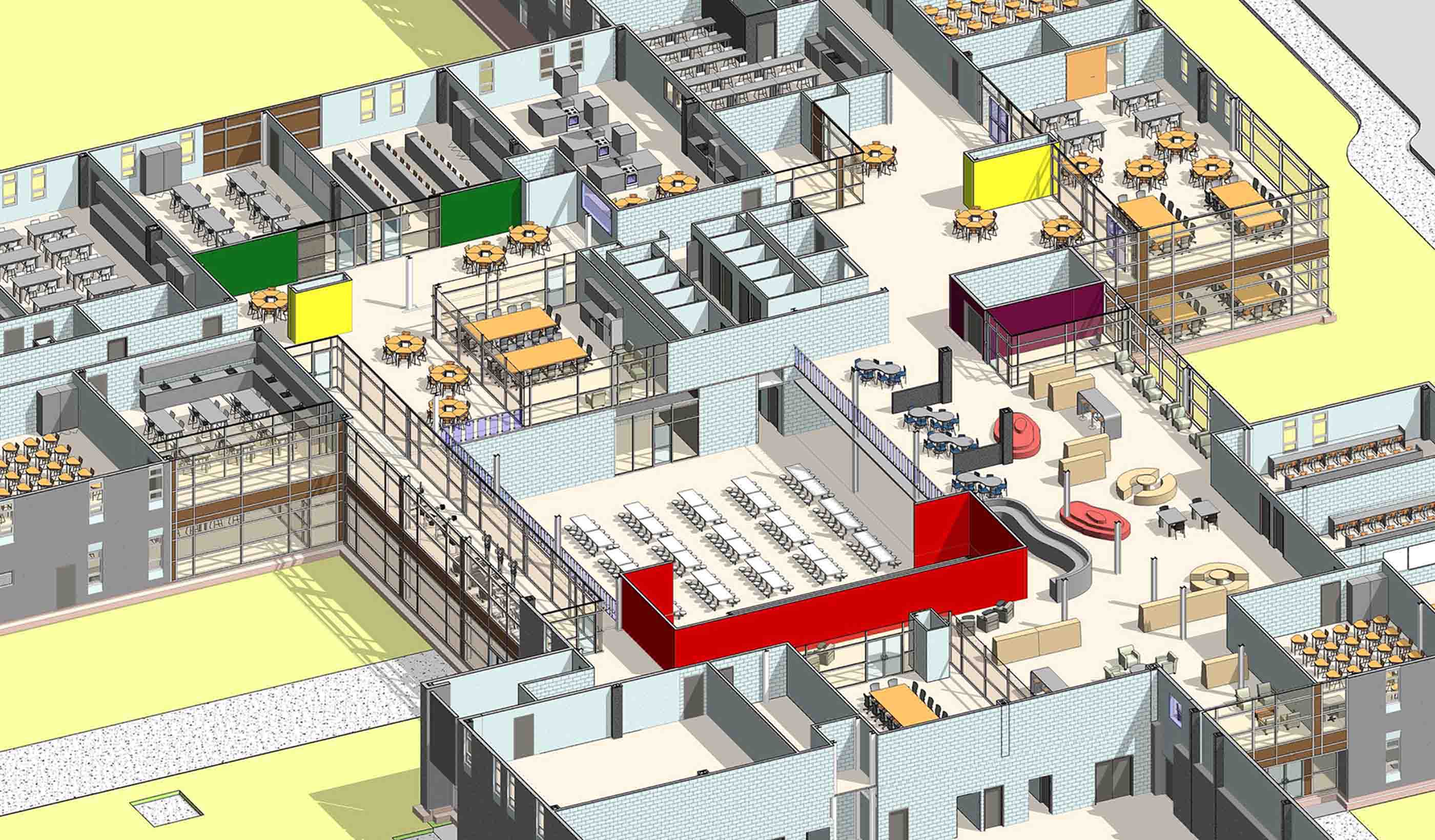

Blog Post 4 reasons why 3D modeling and BIM are the future of infrastructure design

-

Video Stantec kicks off the United Nations’ Decade on Ecosystem Restoration RIGHT!

-

Published Article How can strategic water resource options deliver best value for all?

-

Blog Post How can hydrogen fuel a more sustainable energy future?

-

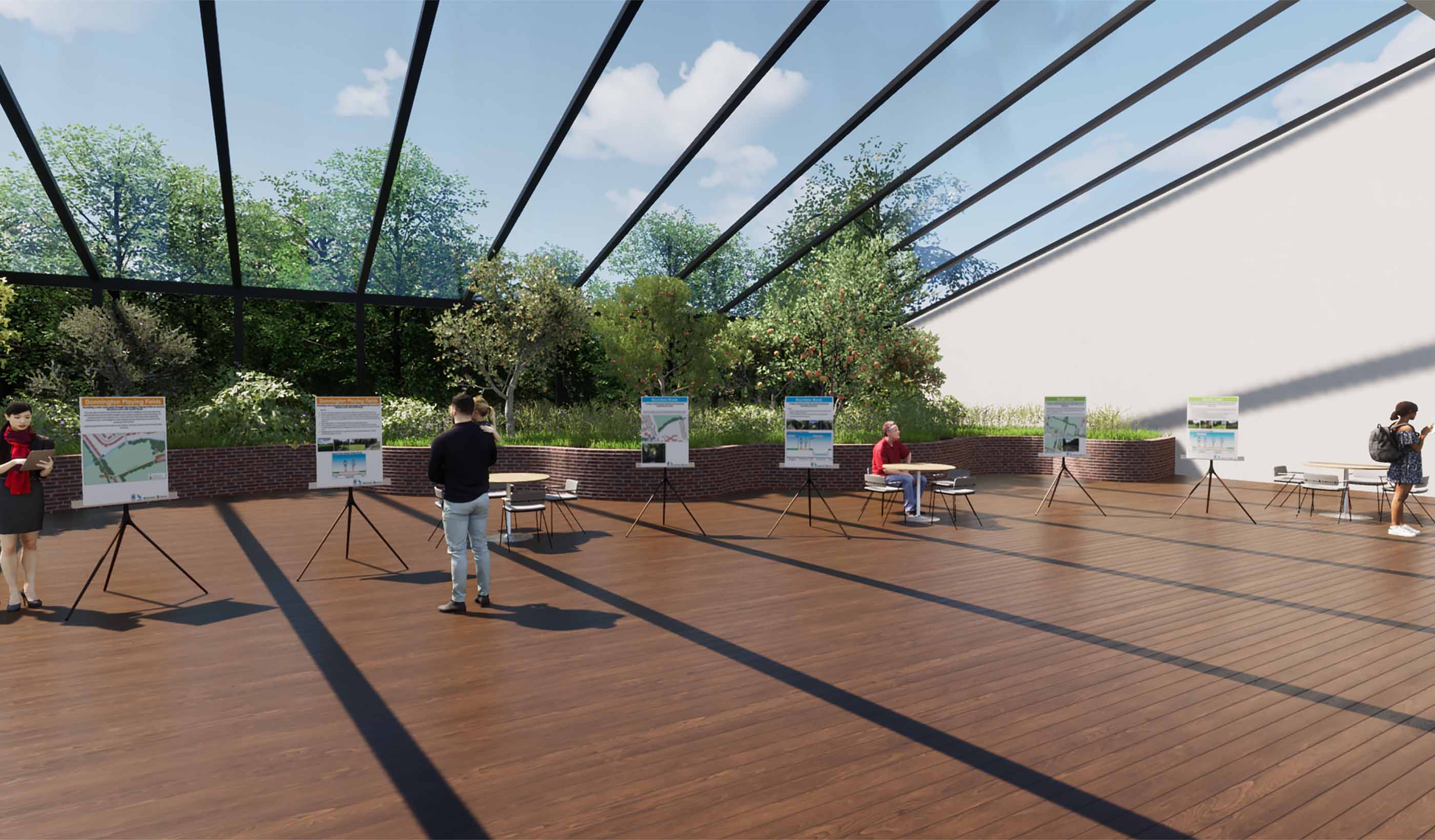

Blog Post Why online consultations are a gamechanger for community engagement

-

Webinar Recording The new permitted development rights: what do they mean for you?

-

Report Better Places (Social Value) Toolkit: Stage 1 Report Summary

-

Report Better Places (Social Value) Toolkit – Stage 1 Report

-

Blog Post Does the Chancellor’s Spending Review help us Build Back Better?

-

Blog Post Harnessing the power of mobile GIS apps to simplify field work and save time, money

-

Publication Water Futures +1 – Water Energy and Agriculture to 2035

-

Published Article How virtual design changes the way we work

-

Published Article Exploring the diffusion of engineering innovation in UK water and sewerage companies

-

Blog Post Working 9 to 5 has been a double climate change whammy

-

Blog Post Carbon: A common language for change—now is the time to act

-

![[With Video] Why VR matters in healthcare design](/content/dam/stantec/images/projects/0053/ucsf-precision-cancer-medicine-bldg-1.jpg)

Blog Post [With Video] Why VR matters in healthcare design

-

Article The how and why of measuring your water footprint

-

Blog Post The pandemic’s lessons in loneliness and aging in place

-

Published Article A system for safety

-

Blog Post Continuing advances in wastewater-to-energy technology

-

Blog Post Did COVID-19 finally push us to completely paperless projects?

-

Blog Post Digital data collection for wildlife surveys leads to better—and faster—information

-

Published Article A glimpse of the future – opportunities to manage surface water

-

Planning Transport & Development

-

Blog Post Scanning smarter: Using reality capture on renovations

-

Article Digital Impact Assessment: A Primer for Embracing Innovation and Digital Working

-

Blog Post Delivering clean, smart and inclusive growth: Rebooting the transport and places skills agenda

-

Published Article Published in the Institute of Water Magazine: Tackling the Climate Emergency

-

Blog Post Helping our planning clients adapt to virtual ways of working

-

Publication Places First: Volume 2

-

Publication Places First: Volume 1

-

Report Charging into the 4th Industrial Revolution

-

Blog Post How will energy demand change in the post-COVID-19 world?

-

Webinar Recording Electric Futures

-

Blog Post A global view of design and urban planning post-COVID-19 (Part 3): New infrastructure

-

Blog Post The transformation of engagement: Community considerations for driving online conversation

-

Blog Post So, what happens when it’s time to get back to the office?

-

Blog Post A global view of design and urban planning post-COVID-19 (Part 2): Changing perspectives

-

Published Article Published: Seize the Moment and Shift the Dial

-

Blog Post A global view of design and urban planning post-COVID-19 (Part 1): Pandemic prevention

-

Blog Post Disaster preparedness in the midst of COVID-19

-

Published Article Published: Delivering compliance through effective environmental management

-

Video Impact of COVID-19 on water/wastewater utilities

-

Webinar Recording The UK digital water utility experience

-

Blog Post Can drone technology help us mitigate the impact of future natural disasters? Absolutely

-

Blog Post Coronavirus and the water cycle—here is what treatment professionals need to know

-

Published Article Published: Rising to the challenge of delivering the largest ever UK national environmental programme

-

Published Article Published in Waterbriefing: A new approach to water resource planning

-

Blog Post From Stantec ERA: 5 ways 3D modeling is changing the way we design power projects

-

Published Article Published in Waterbriefing: Helping the UK water sector deliver net zero carbon emissions

-

Blog Post On the leading edge: Decentralized computing can transform smart-mobility infrastructure

-

Video Restoration and resilience post disaster

-

Blog Post We are at the heart of the climate change challenge

-

Blog Post Global Asbestos Awareness Week

-

Published Article Transport planning and the need to deliver more housing

-

Blog Post World Wetlands Day 2019

-

Blog Post Review of BEN Oxford to Cambridge Corridor Development Conference

-

Blog Post World Water Day 2019

-

Article International Women's Day 2019

-

Blog Post Standard method—help or hindrance?

-

Blog Post World Cities Day: Here’s how we can build a better urban life for future generations

-

Publication Community Futures: Think globally, act locally has never mattered more

-

Blog Post The hidden climate impact of the Internet of Things

-

Blog Post Creating communities through citizen science

-

Blog Post Taking our mental health advocacy to new heights across the world

-

Blog Post The Internet of Environment: digitally twinning the planet

-

Published Article Published in the Institute of Water: Delivering change through research-led innovation

-

Published: Could Project 13 deliver a step change in efficiency for the UK water sector?

-

Published in World Water Magazine: Embracing change delivers SMART technologies

-

Published Article Published in Waterbriefing: What next for PR19?

-

Published Article Published on WWT Online: The robots aren't coming... they’re already here

-

Article Predicting the unpredictable: How a Stantec toolbox helps us understand future flood risks

-

Published Article Published in WET News: In Focus — Social value and procurement

-

Published Article Published in Infrastructure Intelligence: The Project 13 initiative—engineering behavioural change

-

Published Article Published in The Institute of Water Magazine: Developing with our water environment

-

Published Article Published in CIWEM Environment Magazine: Creating a flood-resilient future for Yorkshire

-

Published Article Published in WET News: Focusing on what matters to customers

-

Blog Post Blockchaining ecosystem services to provide natural capital accounting

-

Blog Post Budget 2018: A development & infrastructure view

-

Blog Post Planning for life beyond HS2

-

Blog Post BREEAM New Construction 2018 – Part Two

-

Blog Post Are we keeping pace with climate change?

-

Blog Post BREEAM New Construction 2018 – Part One

-

Blog Post Putting Places First

-

Published Article Published: Making The Most Of What You Have—Optimisation Of Assets In Water And Energy

-

Blog Post The Road to Zero or the Road to Roadworks?

-

Article Stantec supports ICE Scotland to Build Bridges to Schools

-

Blog Post The flying menace coming to a city near you!

-

Blog Post New housing numbers and new population projections: all crystal clear now?

-

Published Article Collaboration Re-Defined: Positioning for Success at PR19

-

Blog Post Power poverty: the new paradigm for social and economic inequality of electric vehicles

-

Navigating the draft revised National Planning Policy Framework

-

Blog Post Urban Greening and the Draft New London Plan

-

Blog Post World Wetlands Day 2018

-

Blog Post The healthy garden city

-

Blog Post The challenges of post-decision monitoring in EIAs

-

Blog Post Garden cities: lighter, faster, cheaper

-

Blog Post Garden cities & movement: achieving 'good growth'

-

Blog Post Housing need: what can we learn from the new CLG proposals?

-

Blog Post Vehicle for change

-

Blog Post The changing face of freight and logistics

-

Turning transport planning on its head: part II

-

Turning transport planning on its head: part I

-

Blog Post Brexit an environmental opportunity

-

Blog Post Explaining the case for infrastructure projects

-

Interactive Can pumped storage fuel a more sustainable future?

-

Interactive The energy transition is about more than renewables

-

Interactive The Four Pillars of Successful Offshore Wind Development Consent Orders

-

Interactive 6 Ways to Meet Your ESG Goals Through Nature

-

Interactive You have an energy transition or climate action plan, but is it integrated?

-

Interactive Stantec is committed to climate action

-

Interactive Coastal resilience by the numbers

-

Sparking Innovation: King’s Scholar’s Pond Sewer Rehabilitation