-

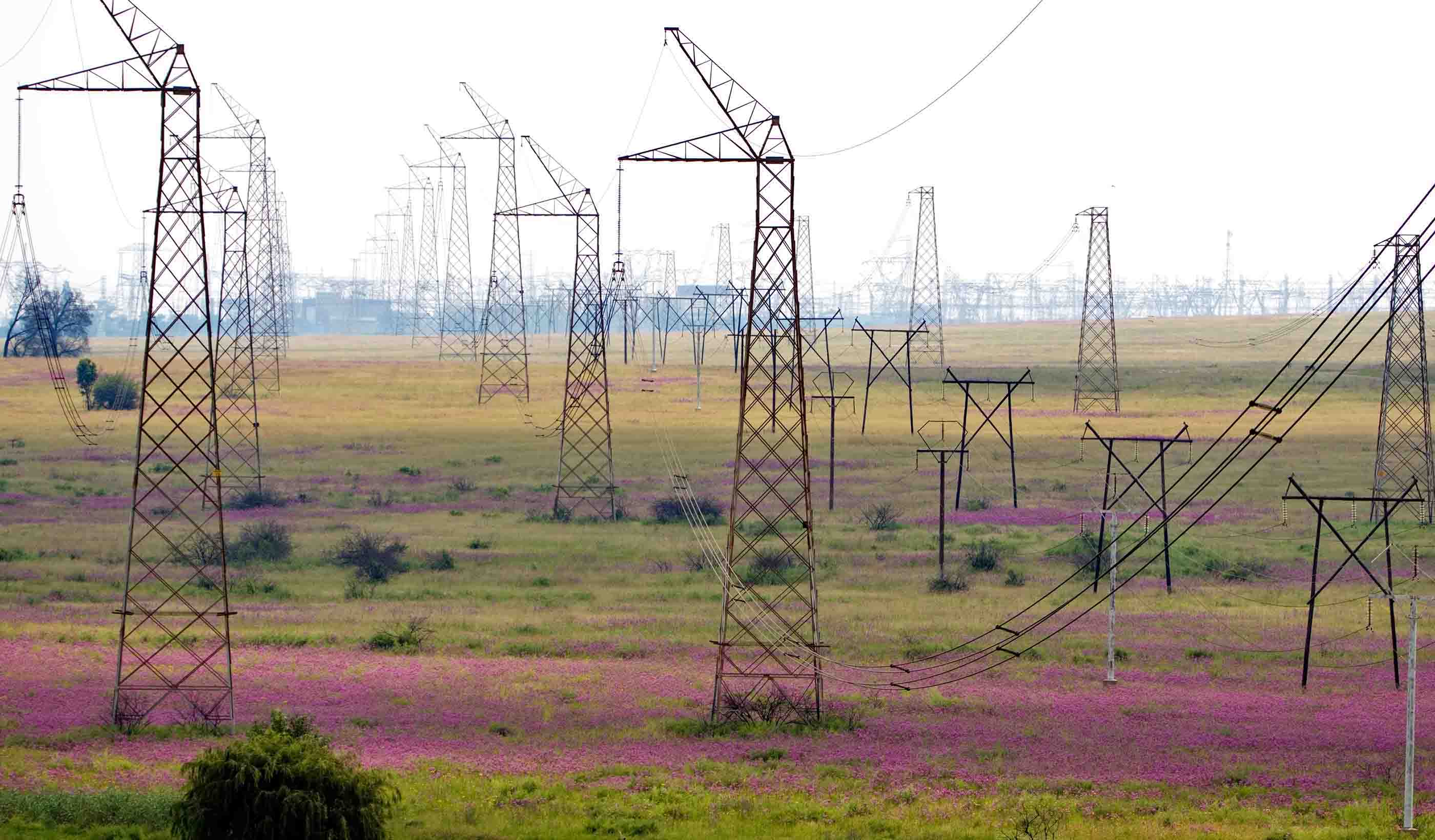

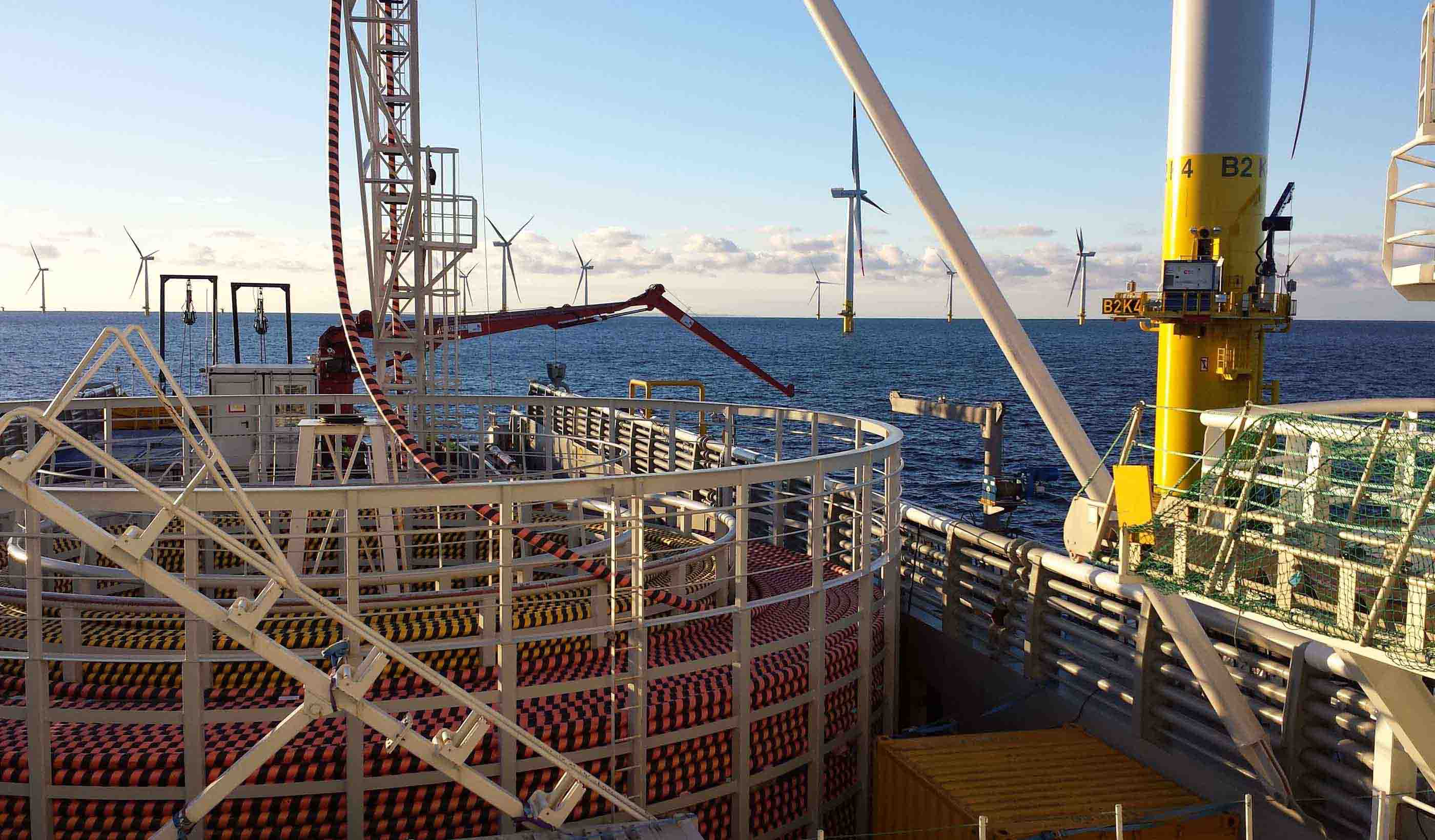

Blog Post 11 key design factors for extra high voltage transmission systems

-

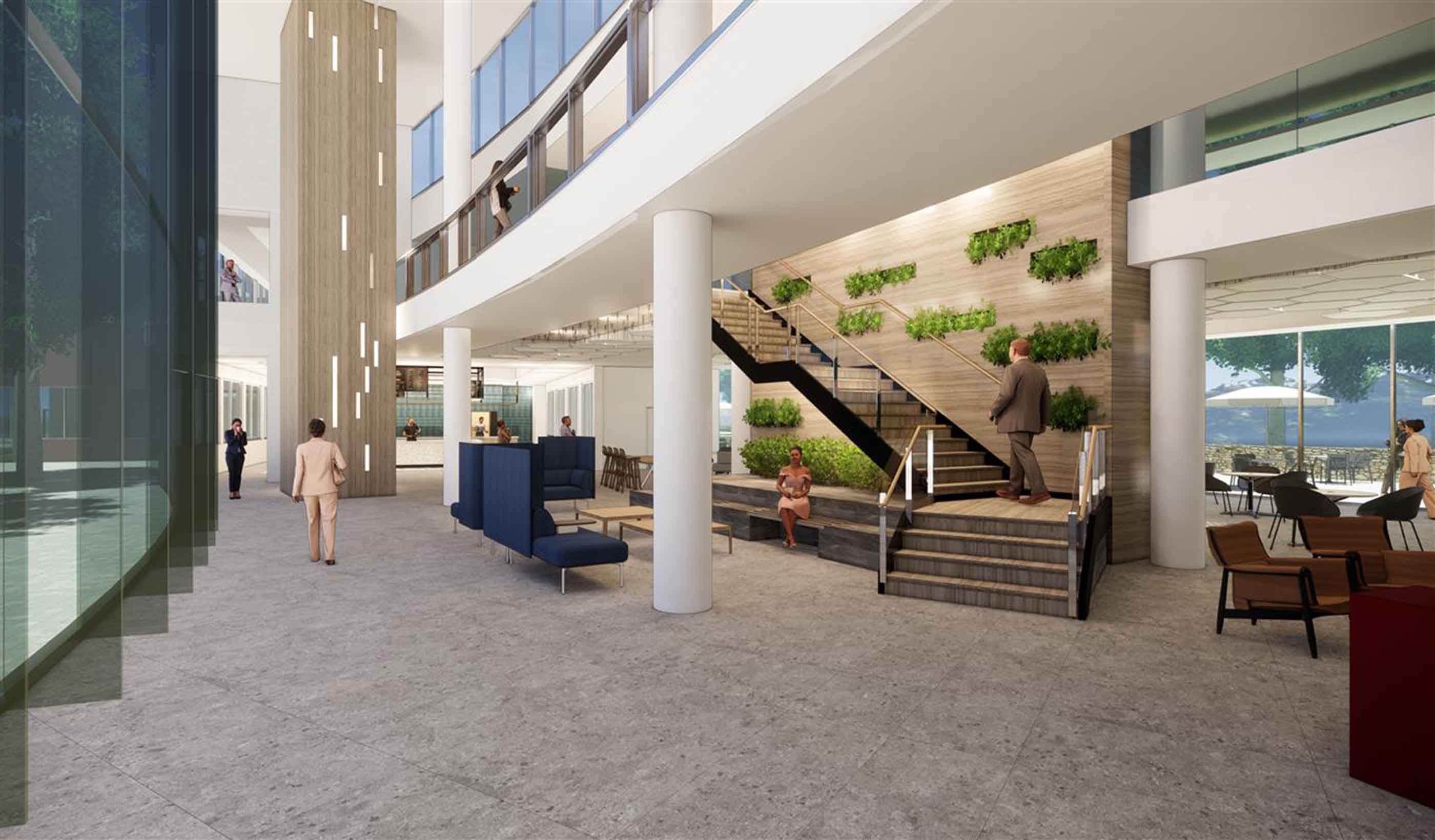

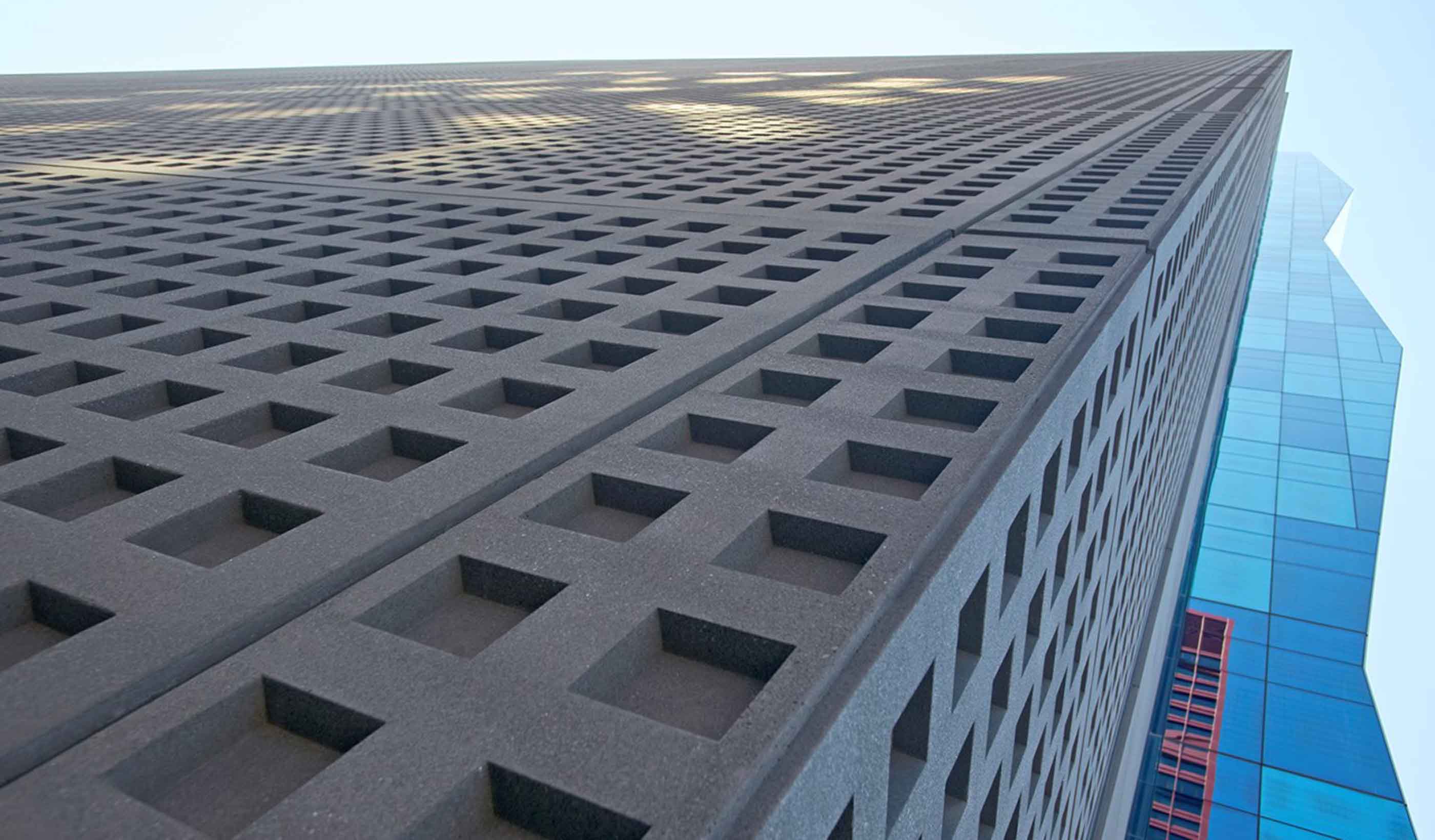

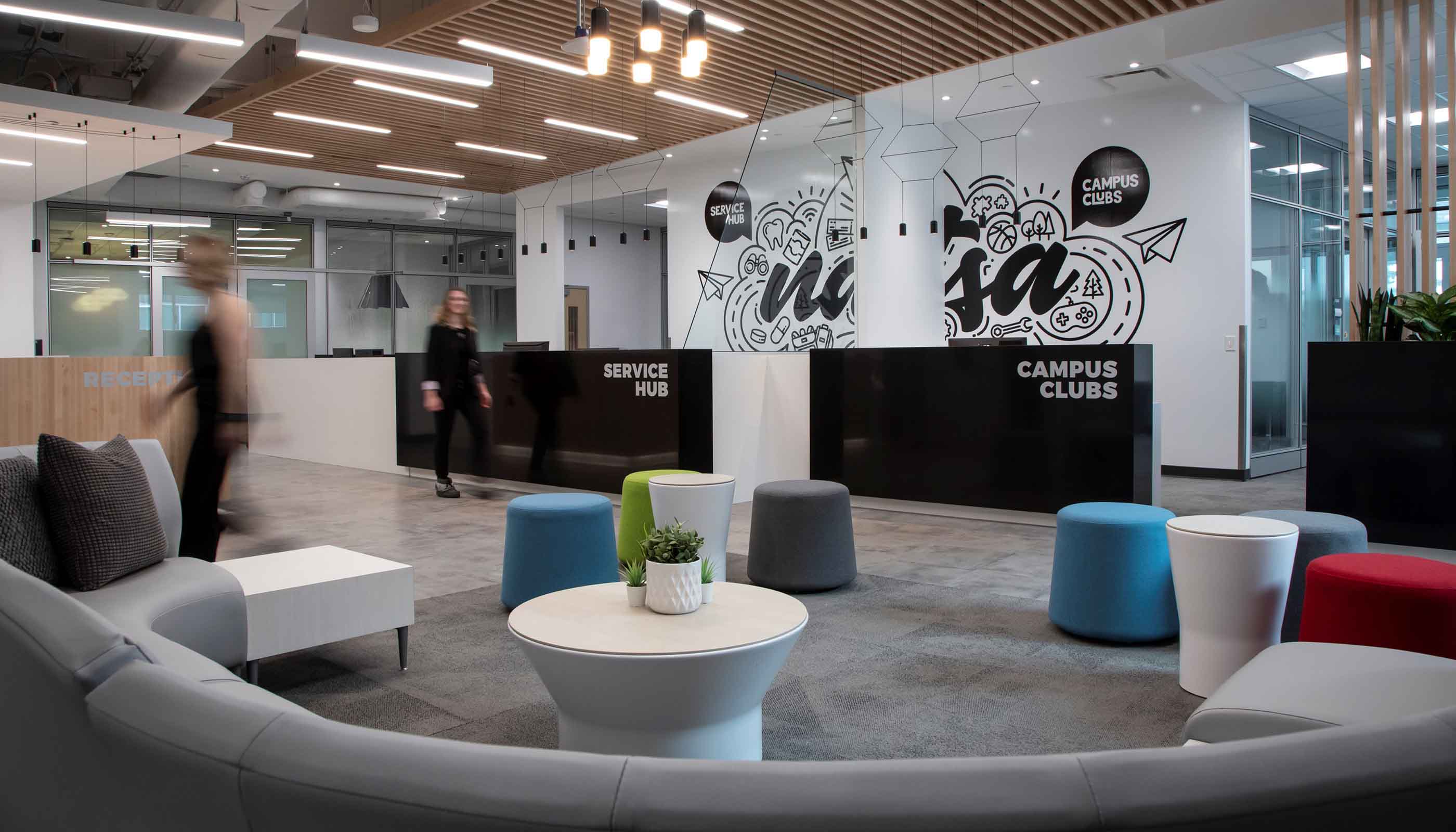

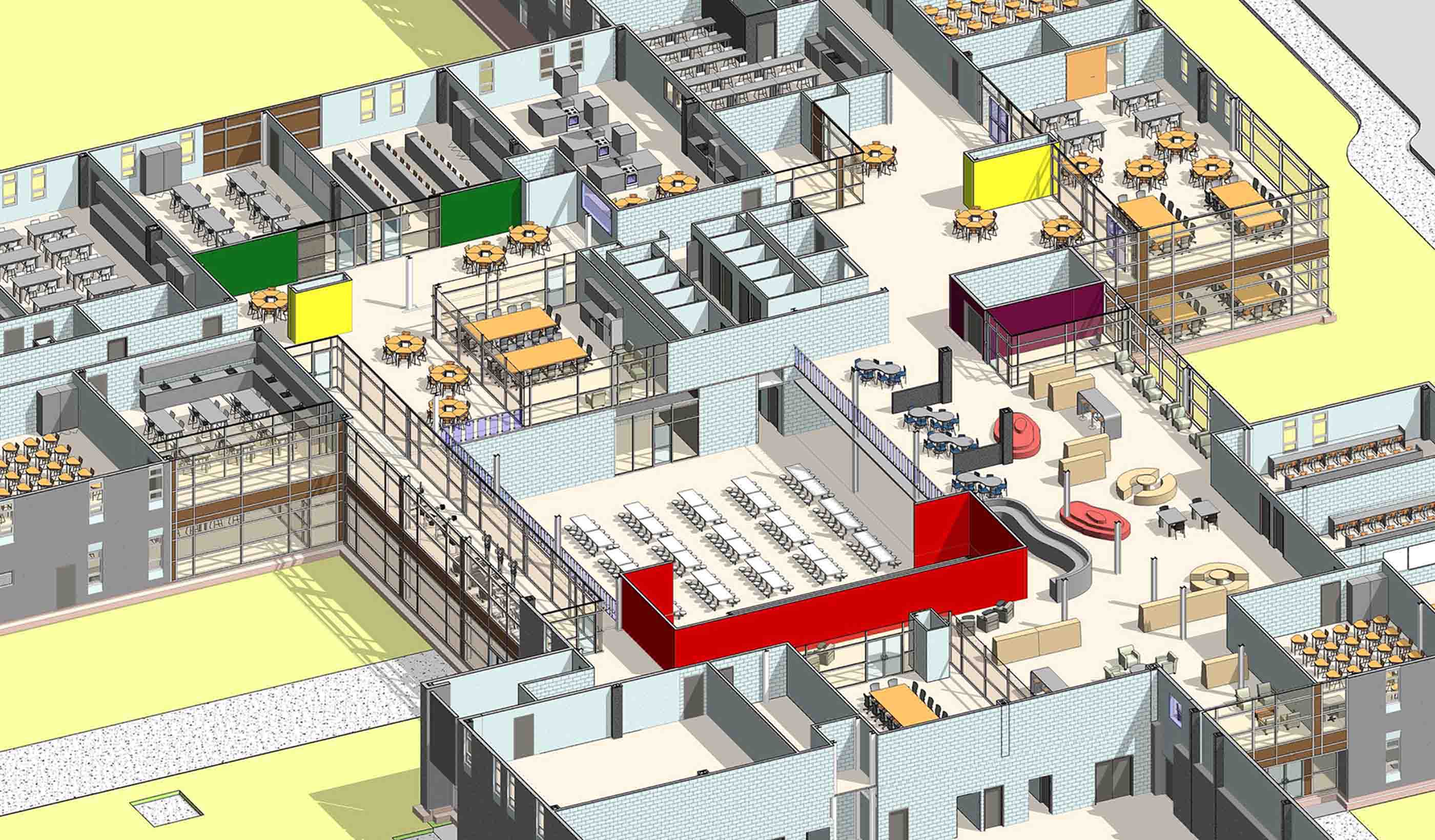

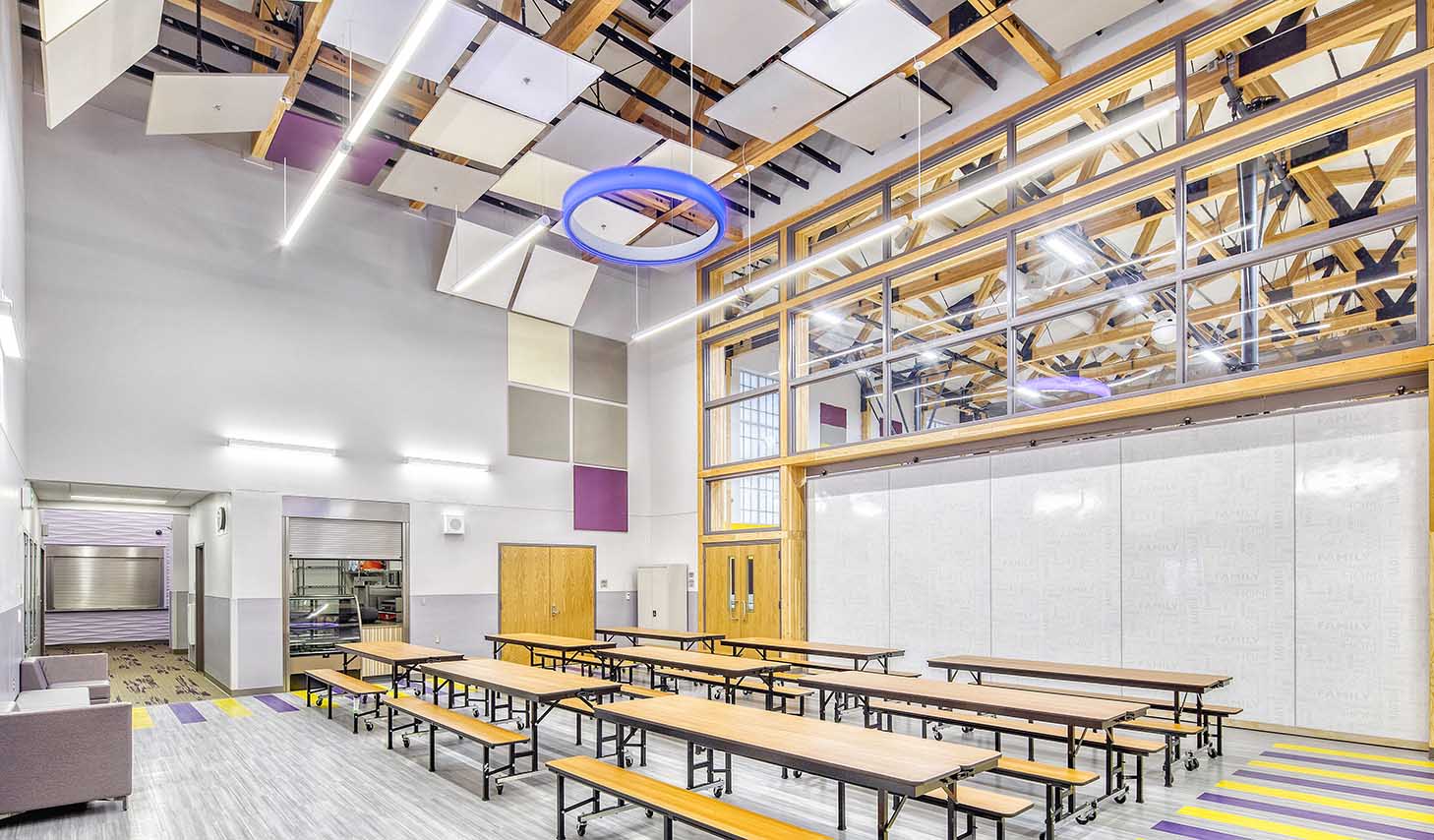

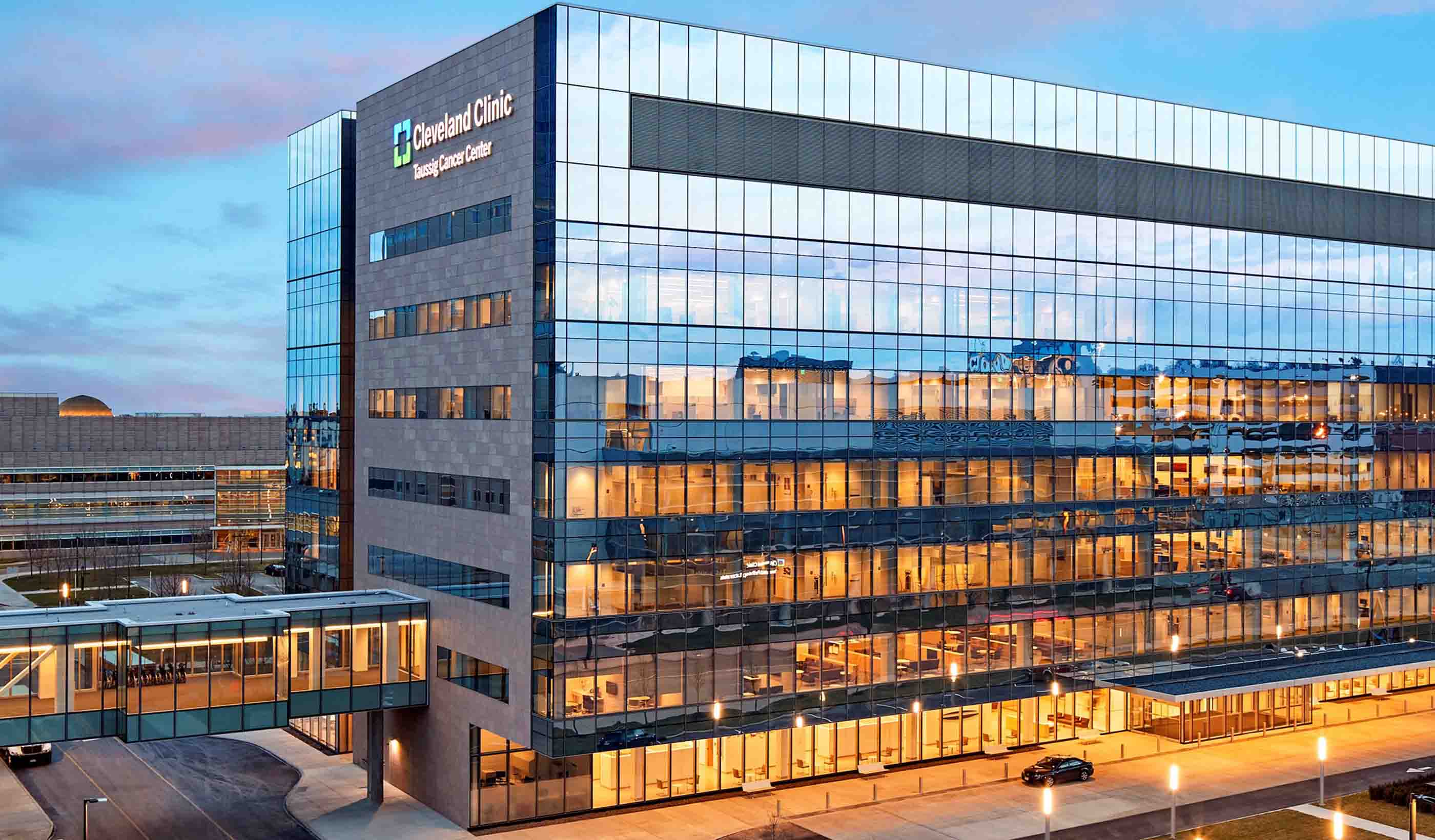

Blog Post Campus buildings: Do we renovate that university building or build a new one?

-

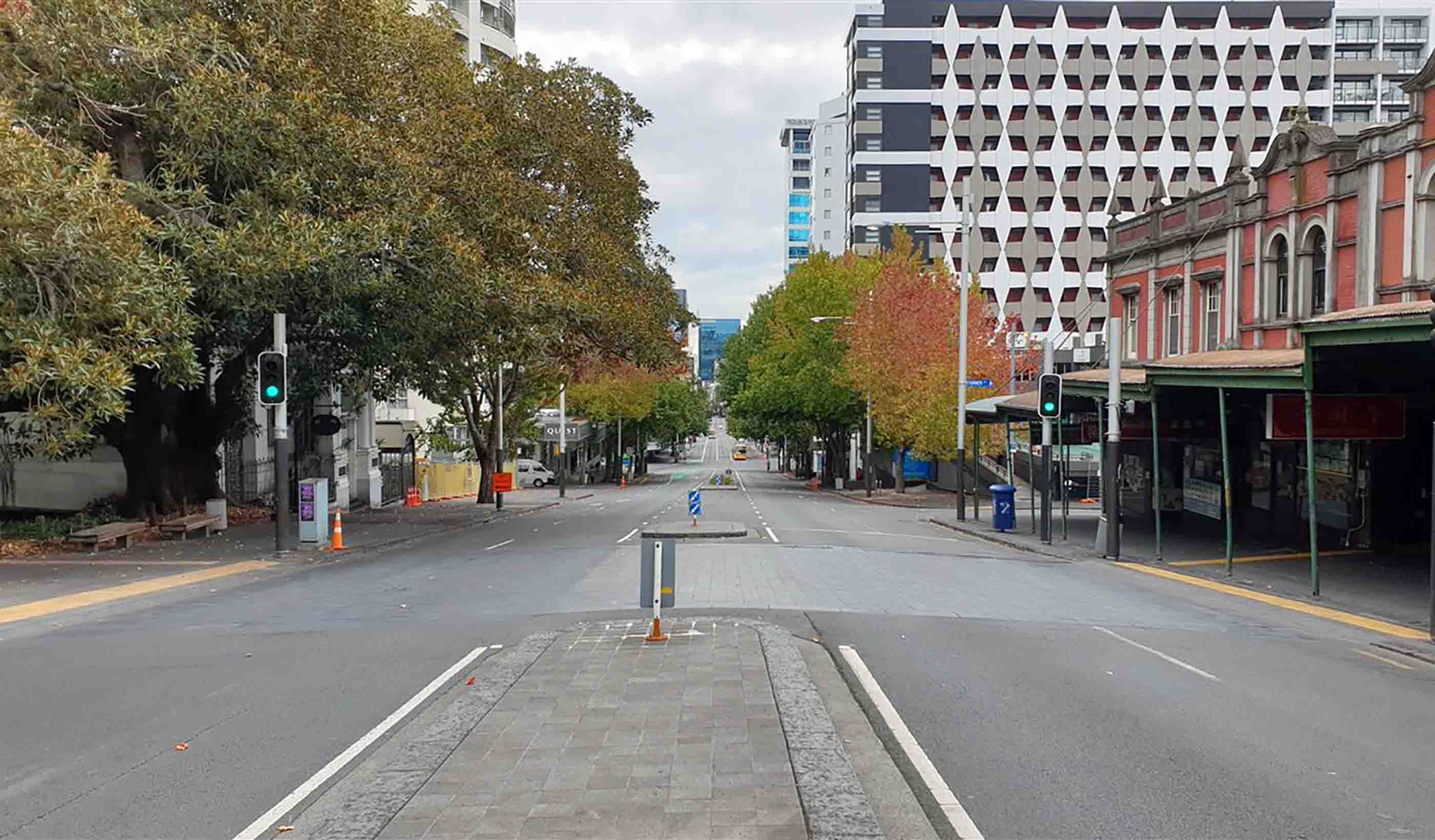

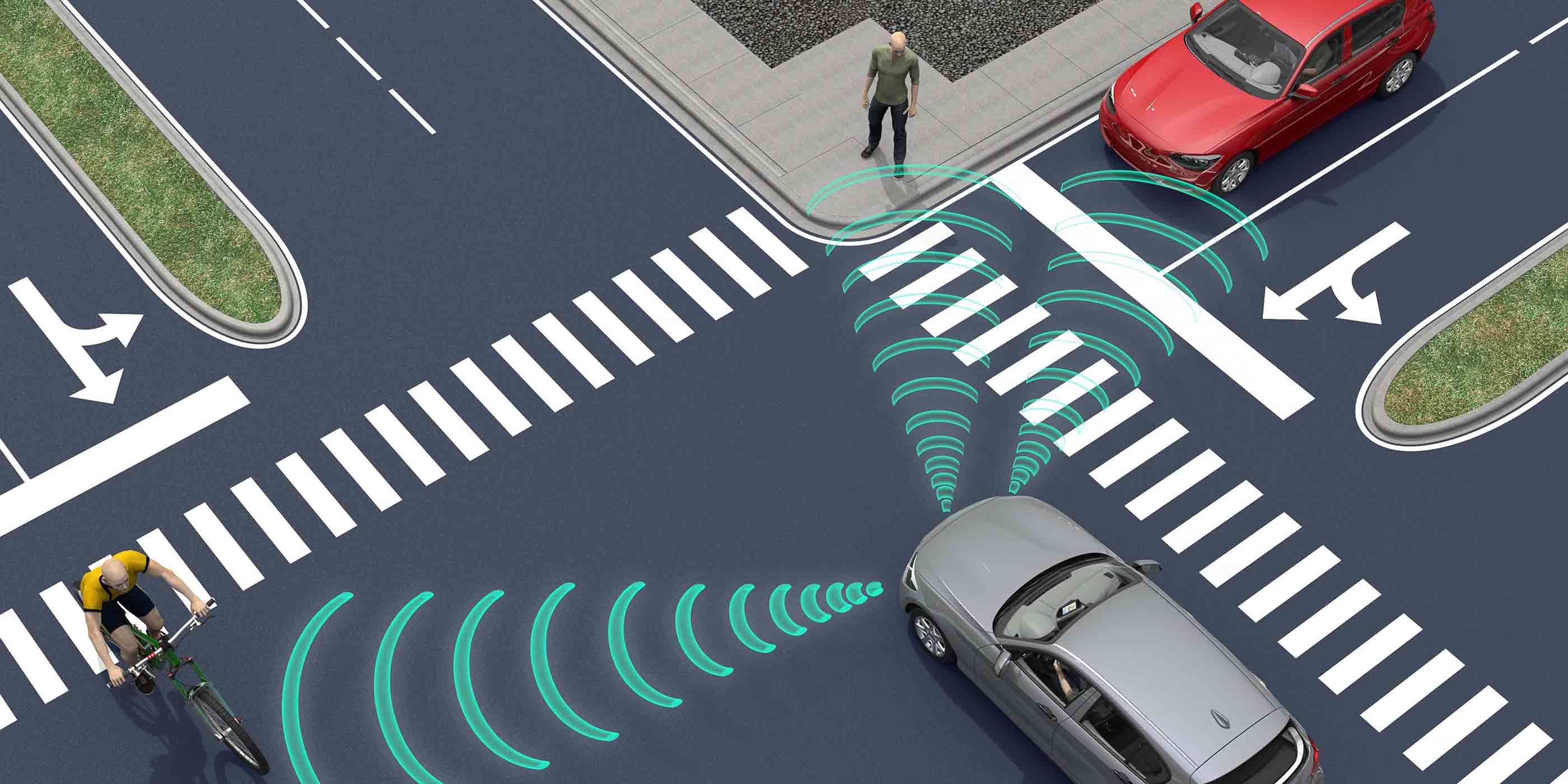

Blog Post What your road safety analysis is missing: 3 important factors

-

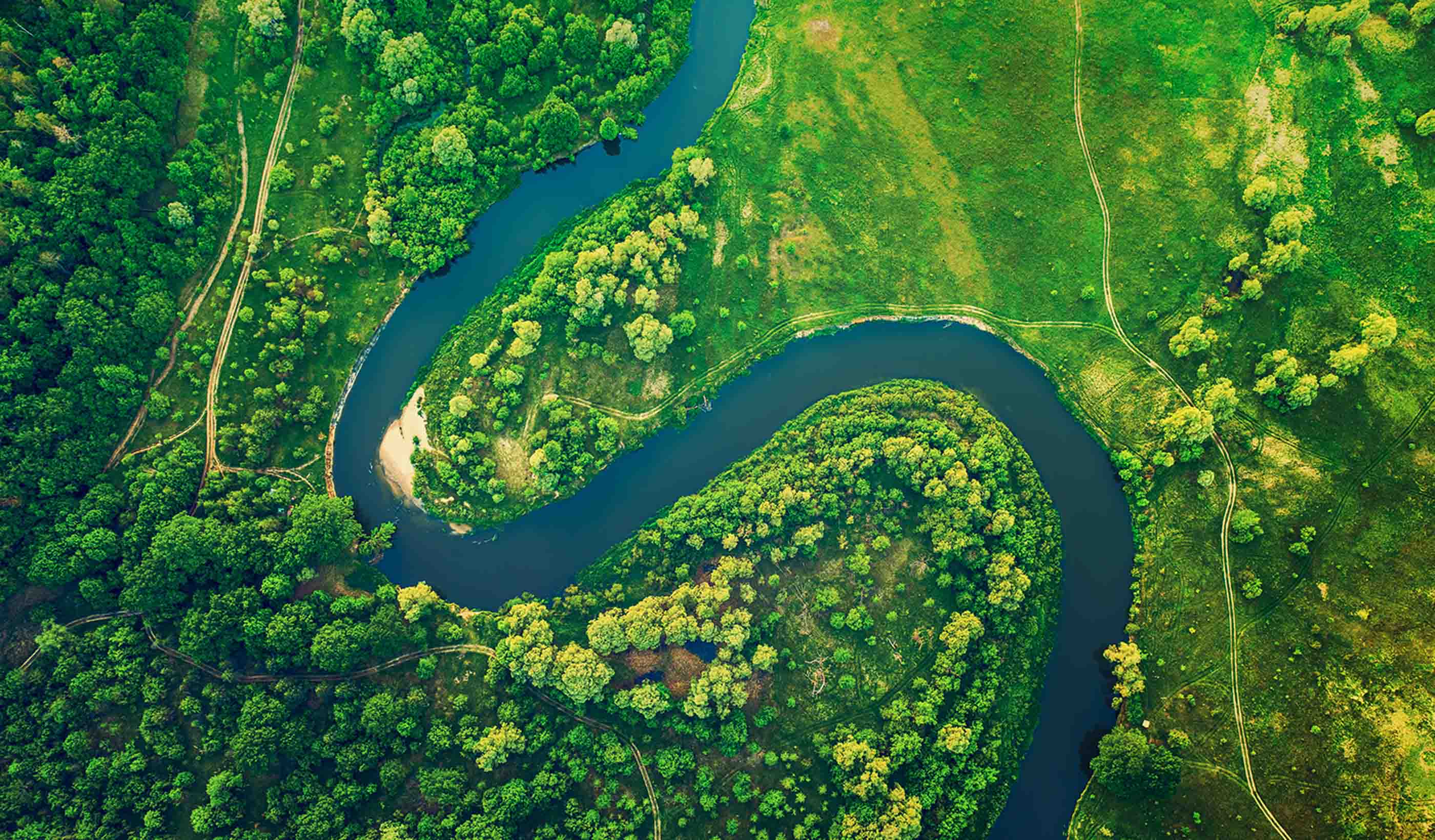

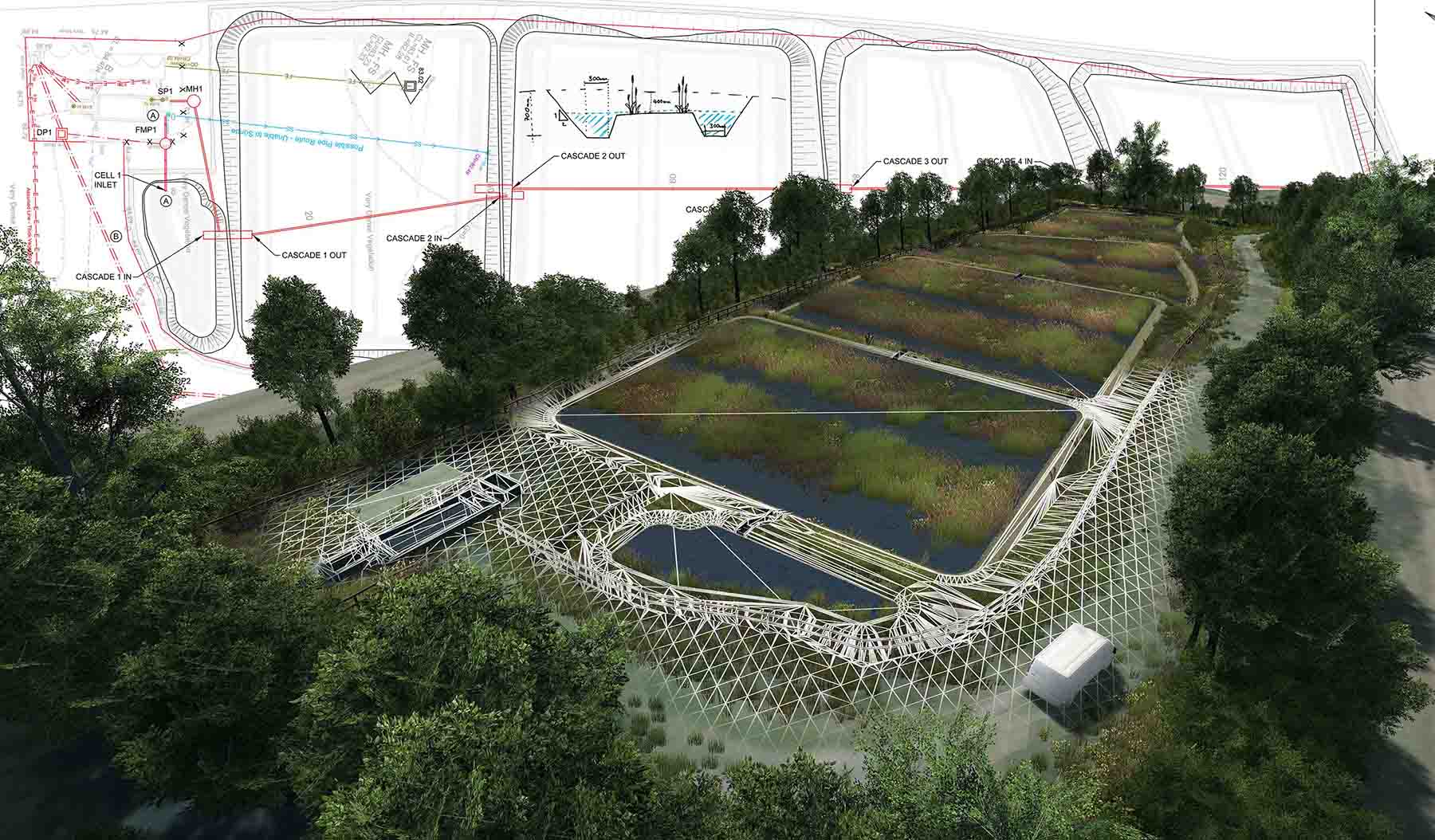

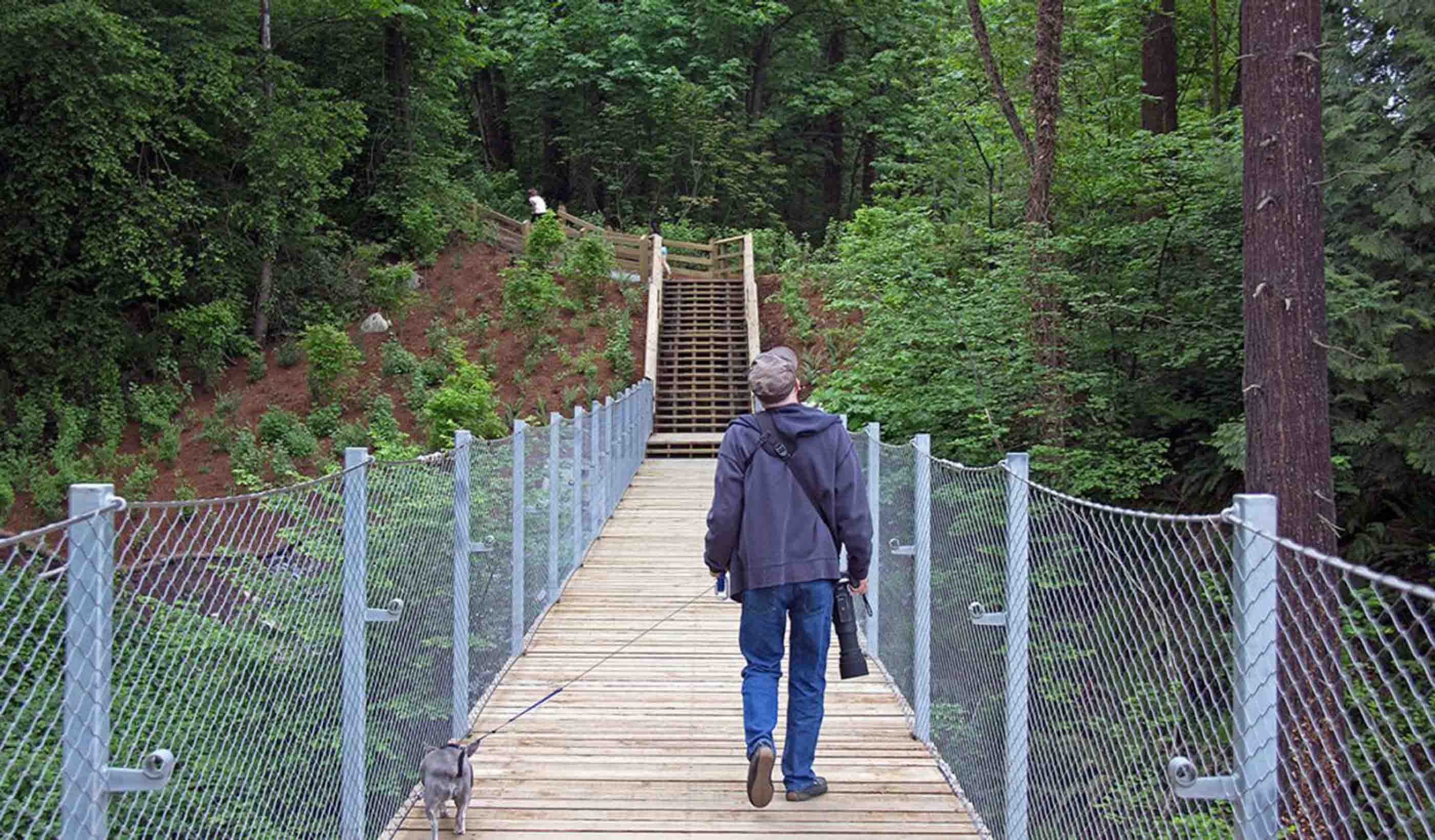

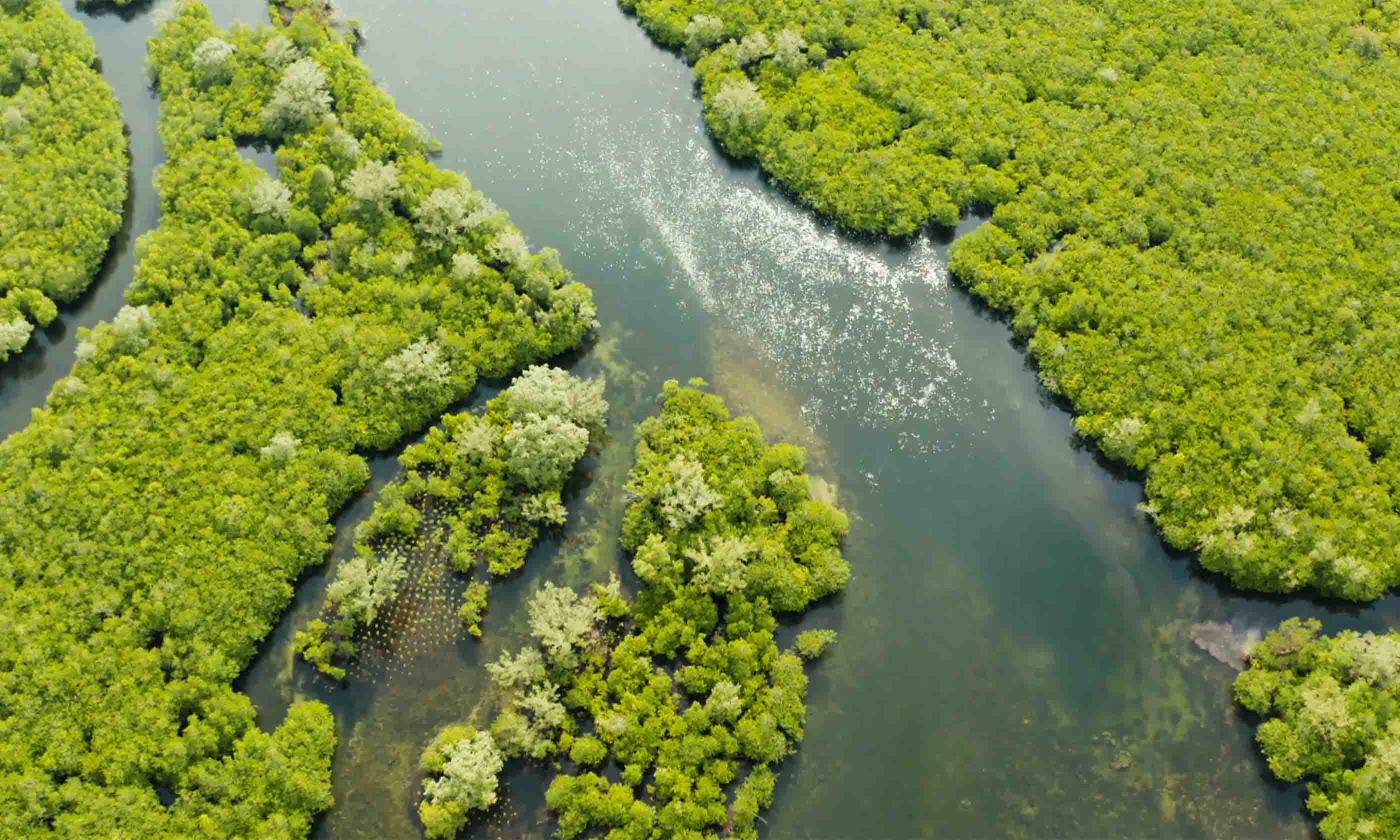

Video How nature-based solutions deliver ROI, resilience, and community benefits

Ideas

Explore the trends, innovations, and challenges impacting the built and natural environments.

All Ideas

-

Blog Post Stantec’s Top 10 Ideas from 2025: AI to ZenDen

-

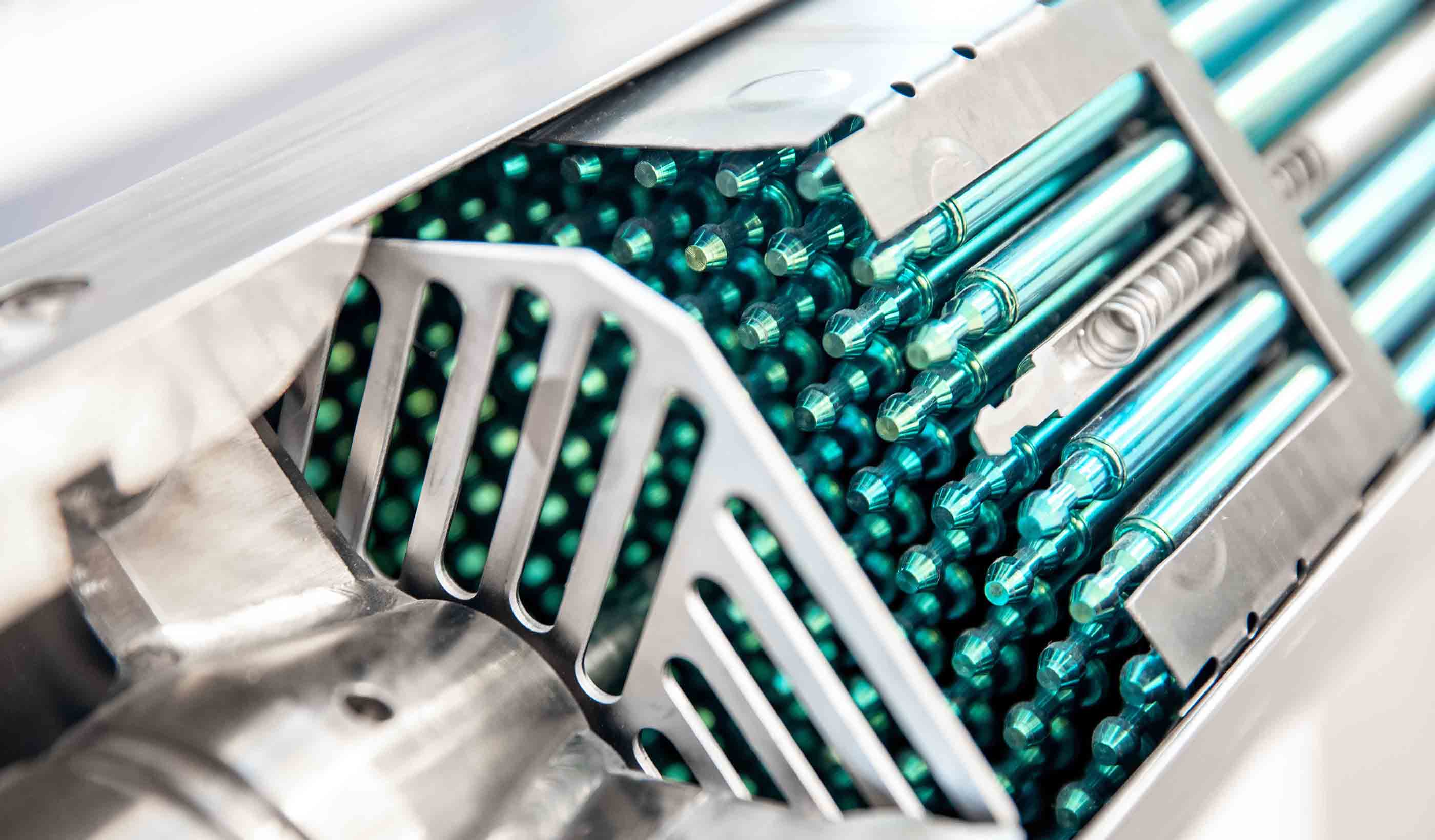

Published Article Carbon capture systems for the cement industry

-

Blog Post AI tools for architecture: Designers explore what’s possible

-

Blog Post What your road safety analysis is missing: 3 important factors

-

Blog Post Campus buildings: Do we renovate that university building or build a new one?

-

Blog Post The WELL Building Standard: Making healthy buildings and keeping them that way

-

Blog Post 9 strategies for community revitalization: Lessons learned from Ukraine housing design

-

Blog Post 3 things to know about Florida vulnerability assessments and municipal resiliency goals

-

Blog Post 11 key design factors for extra high voltage transmission systems

-

Podcast Design Hive: William Ketcham on campus development and client service in higher education

-

Blog Post Building envelope design: A next-generation Passive House window and shade connection

-

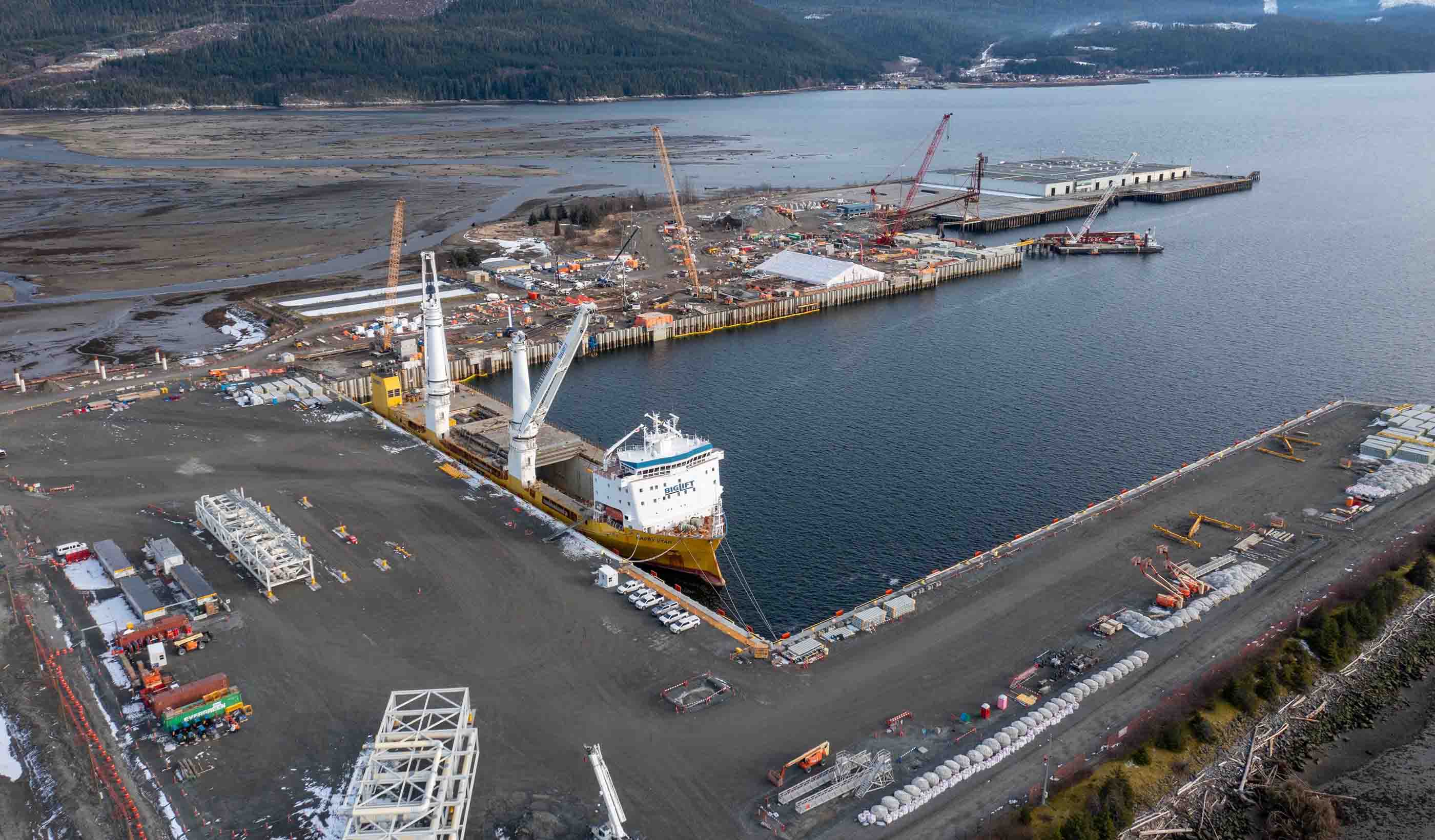

Published Article Laying the keel of resilience: Naval infrastructure for a maritime nation

-

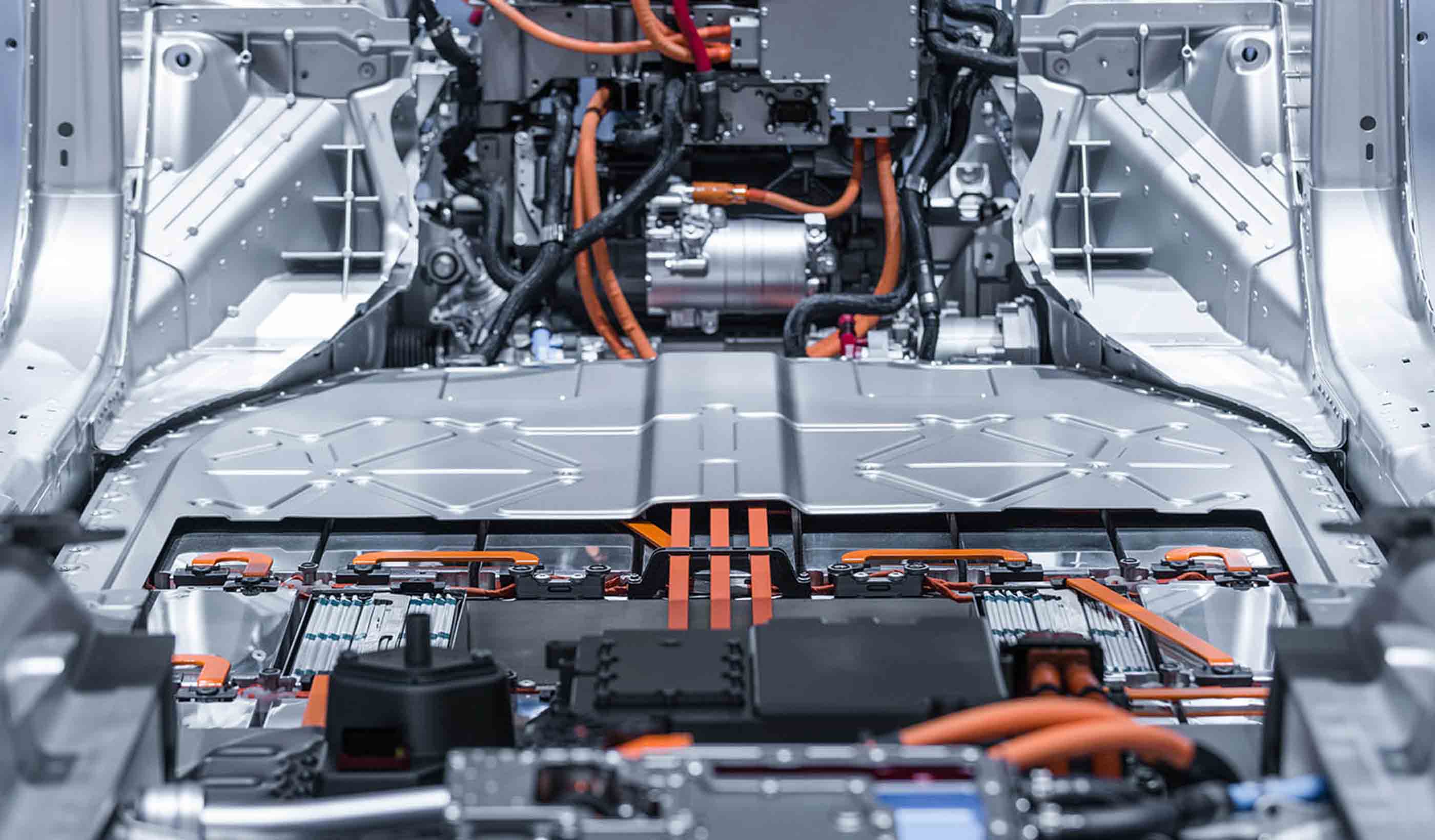

Blog Post Battery electric bus maintenance: 8 things to know about your bus

-

Video How nature-based solutions deliver ROI, resilience, and community benefits

-

Podcast Design Hive: Gary Moss and Greg Hall on advanced manufacturing design

-

Webinar Recording Webinar series: The transformative potential of sustainable building retrofits

-

Webinar Building commissioning webinar: Strategies to enhance long-term value

-

Blog Post Biodiversity and sustainability are essential to reducing corporate risks. Here’s why.

-

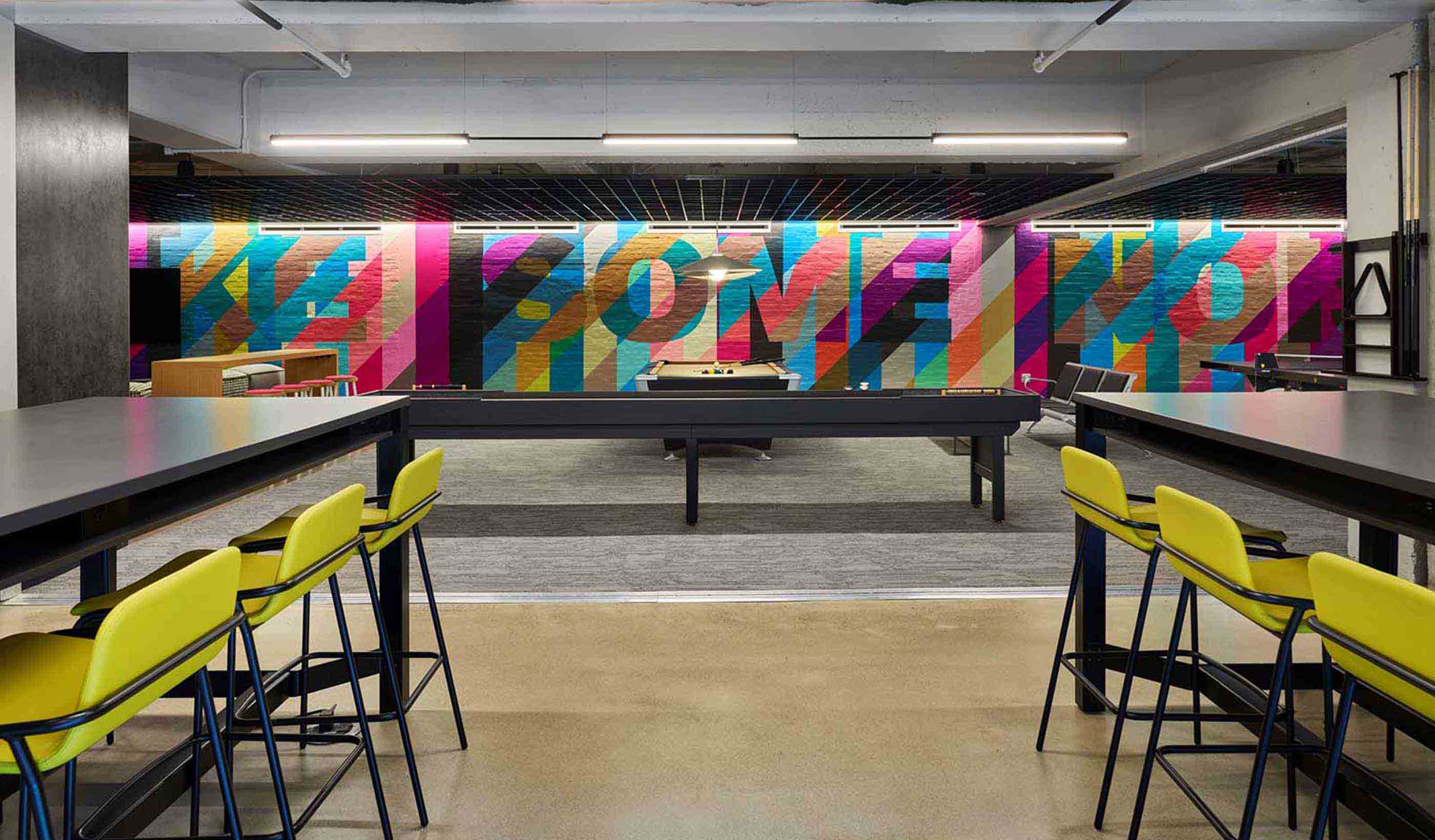

Report Workplace strategy report—State of the Workplace: Now and Next

-

Case Study Community design case study: Creating science station residences in Antarctica

-

Webinar Recording Transforming asset management: The next evolution in operational strategy

-

Video Building Dubai’s first integrated cancer hospital using Autodesk Forma

-

Publication Design Quarterly Issue 26 | Lasting solutions

-

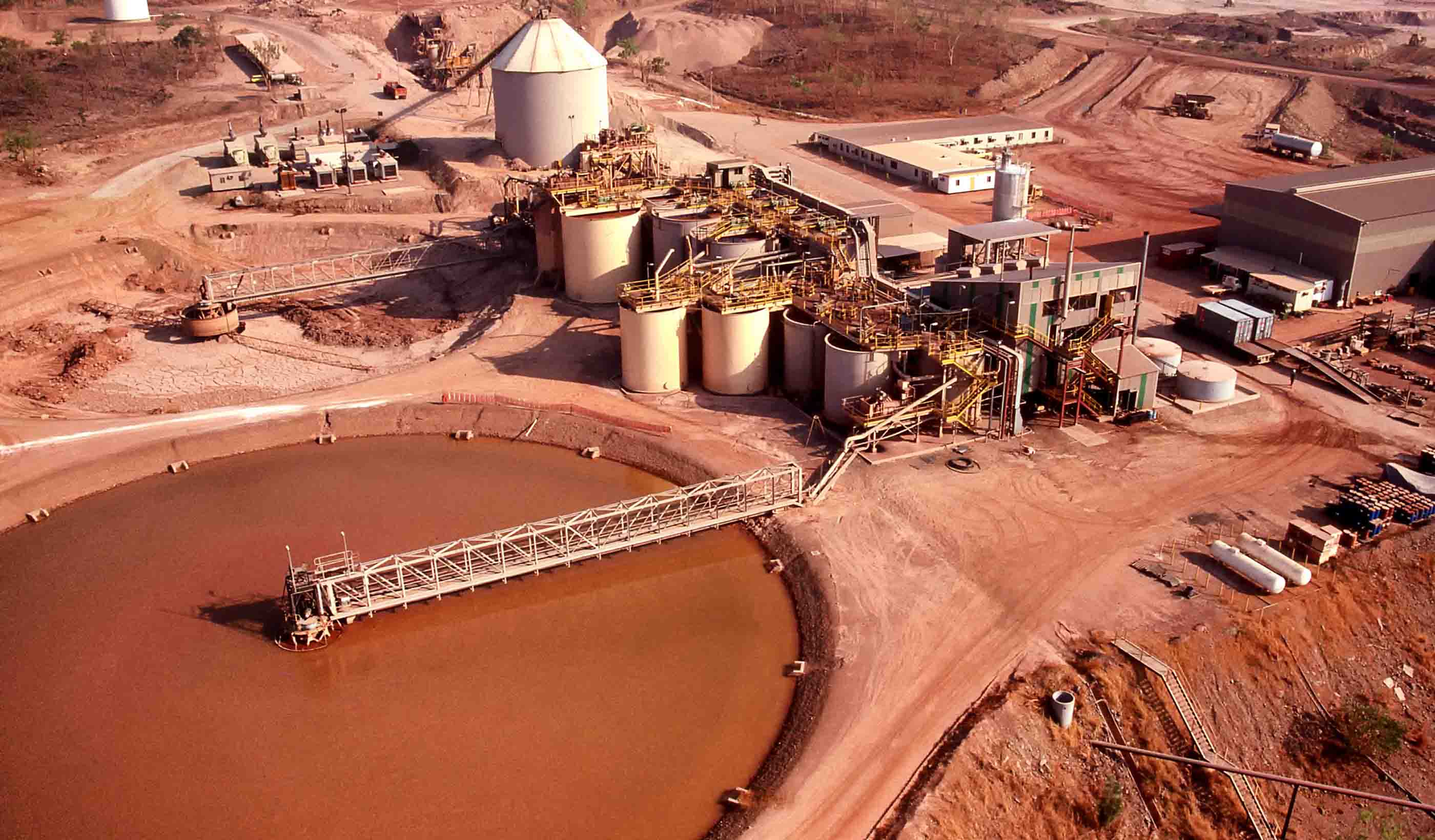

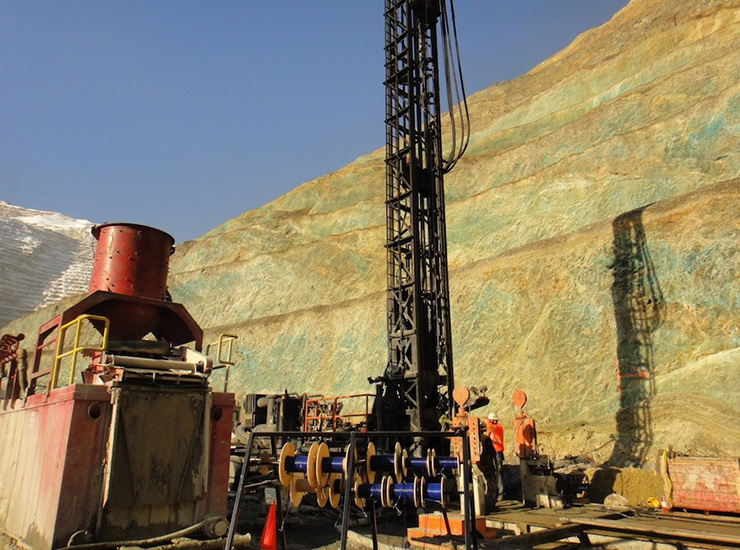

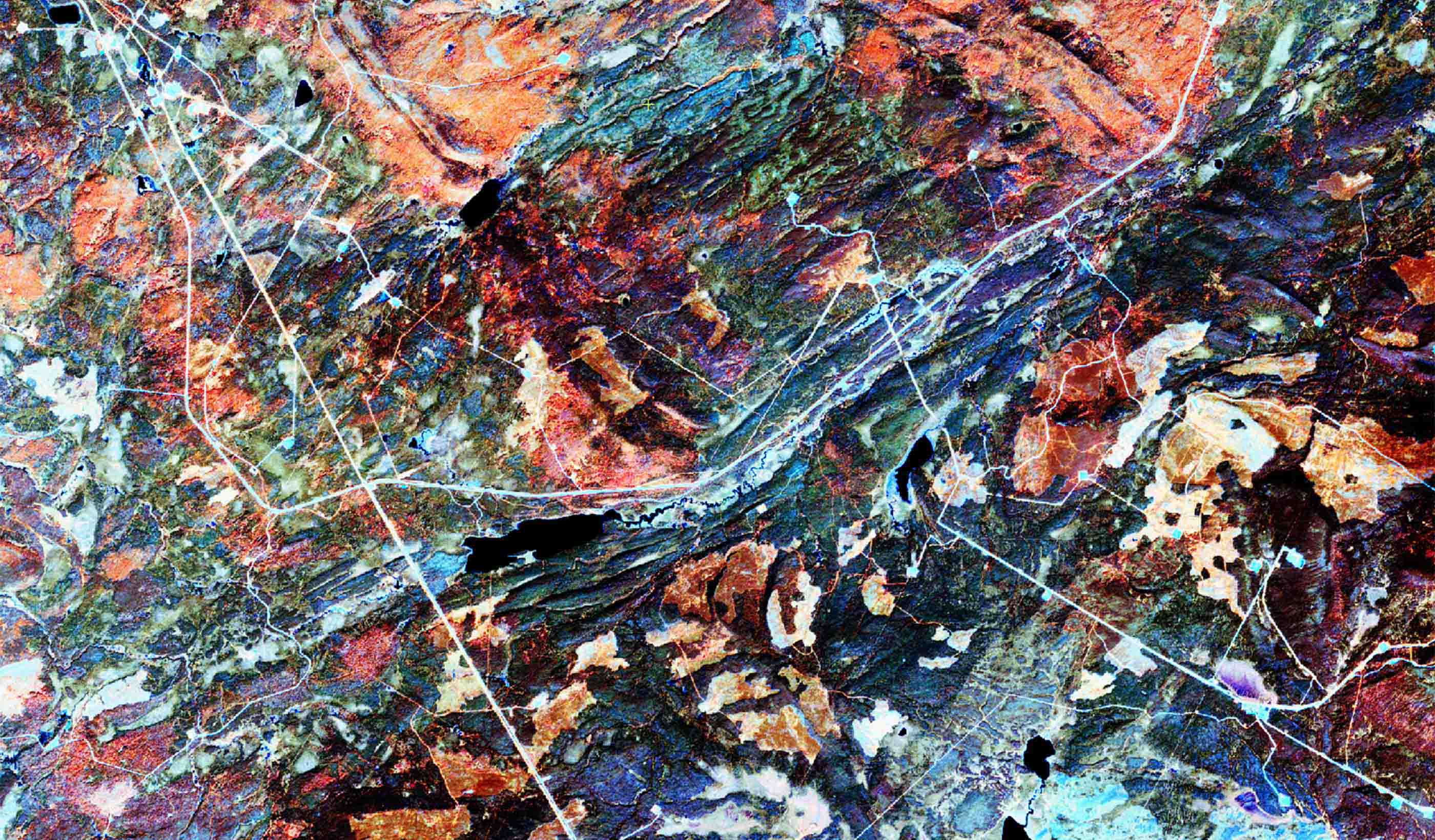

Published Article Critical thinking for critical minerals: Why due diligence matters more than ever

-

Blog Post Nuclear power facility development: How to design the support buildings

-

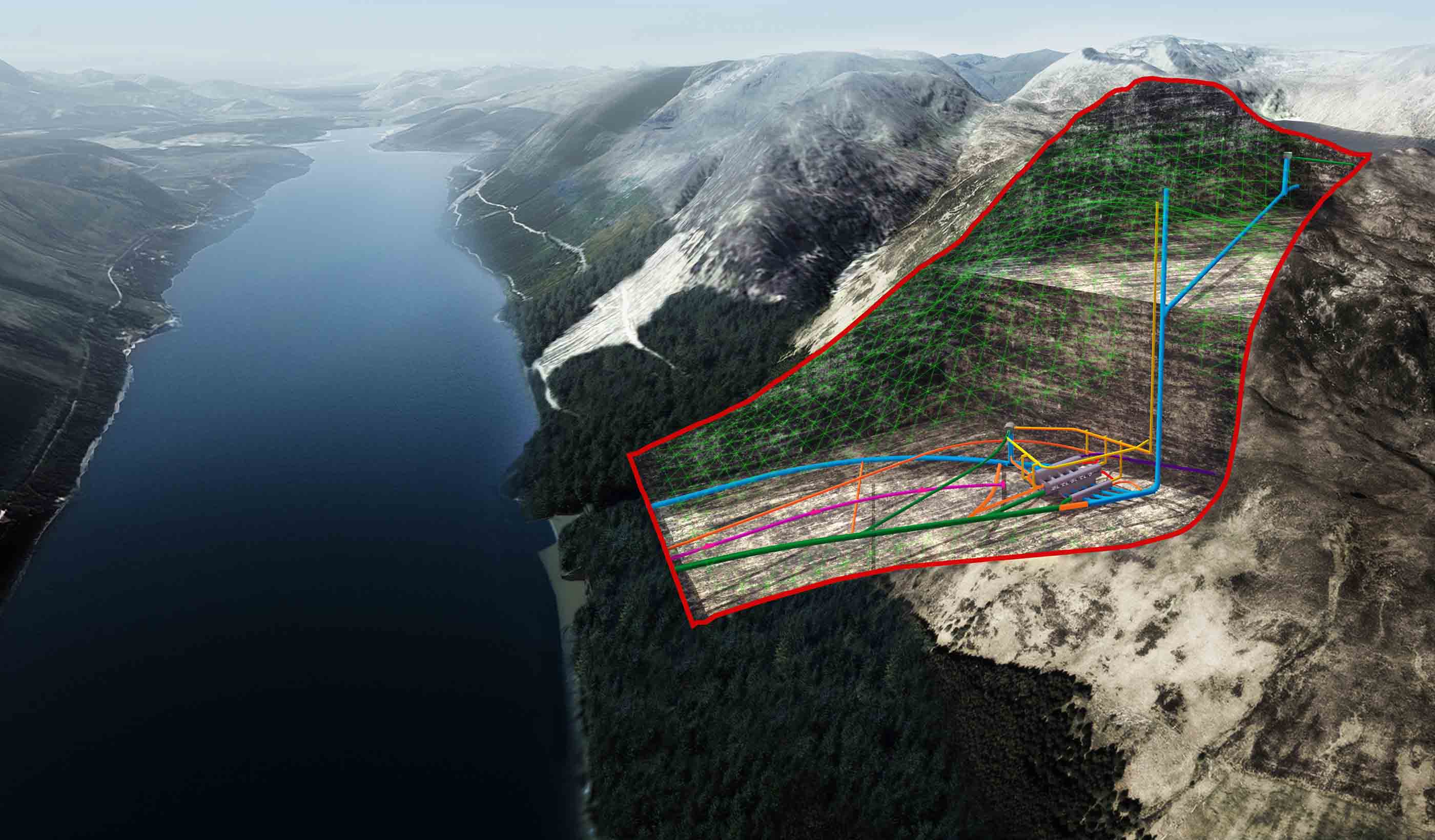

Published Article From data to decisions: How real-time monitoring helps achieve GISTM compliance

-

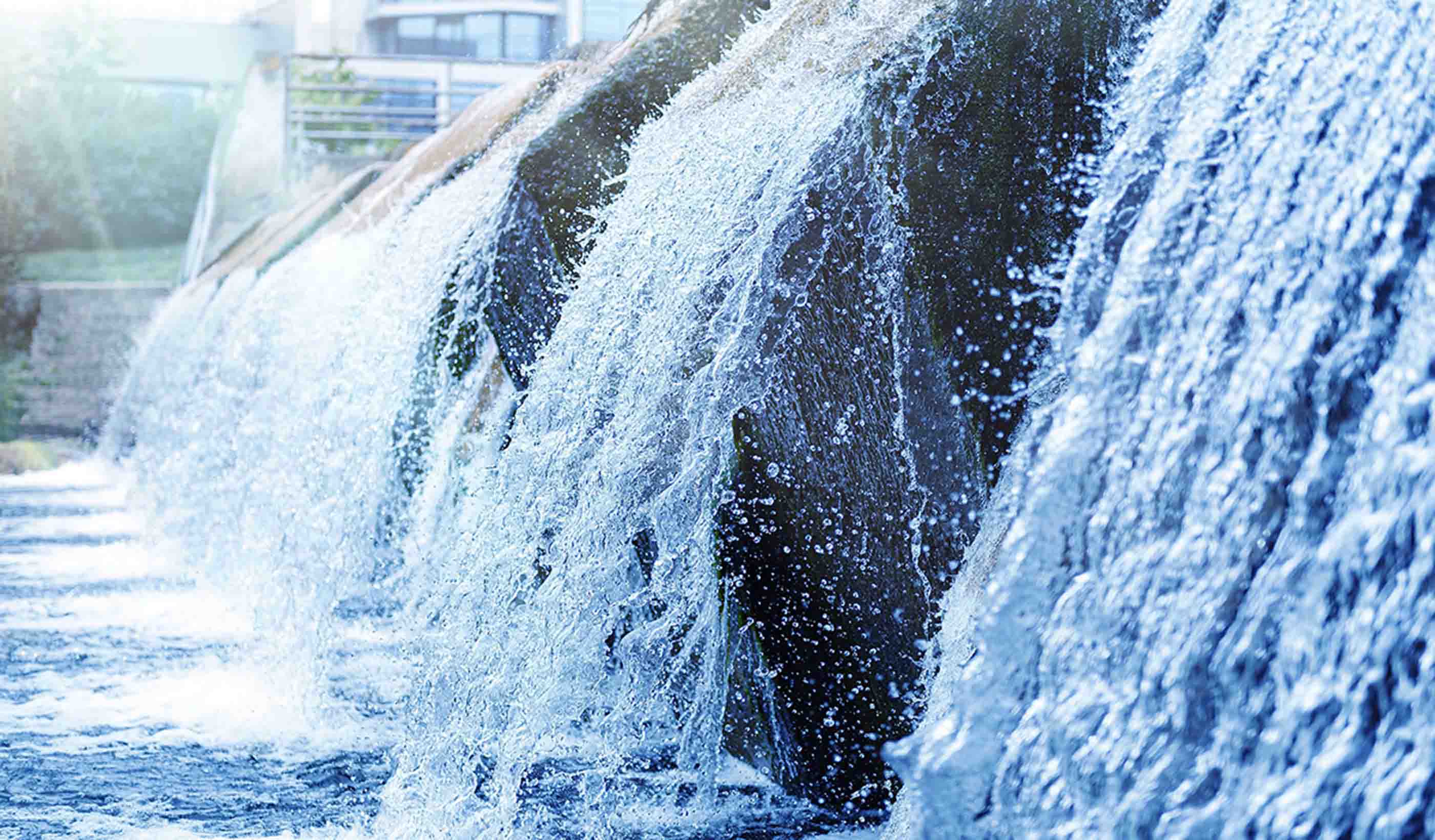

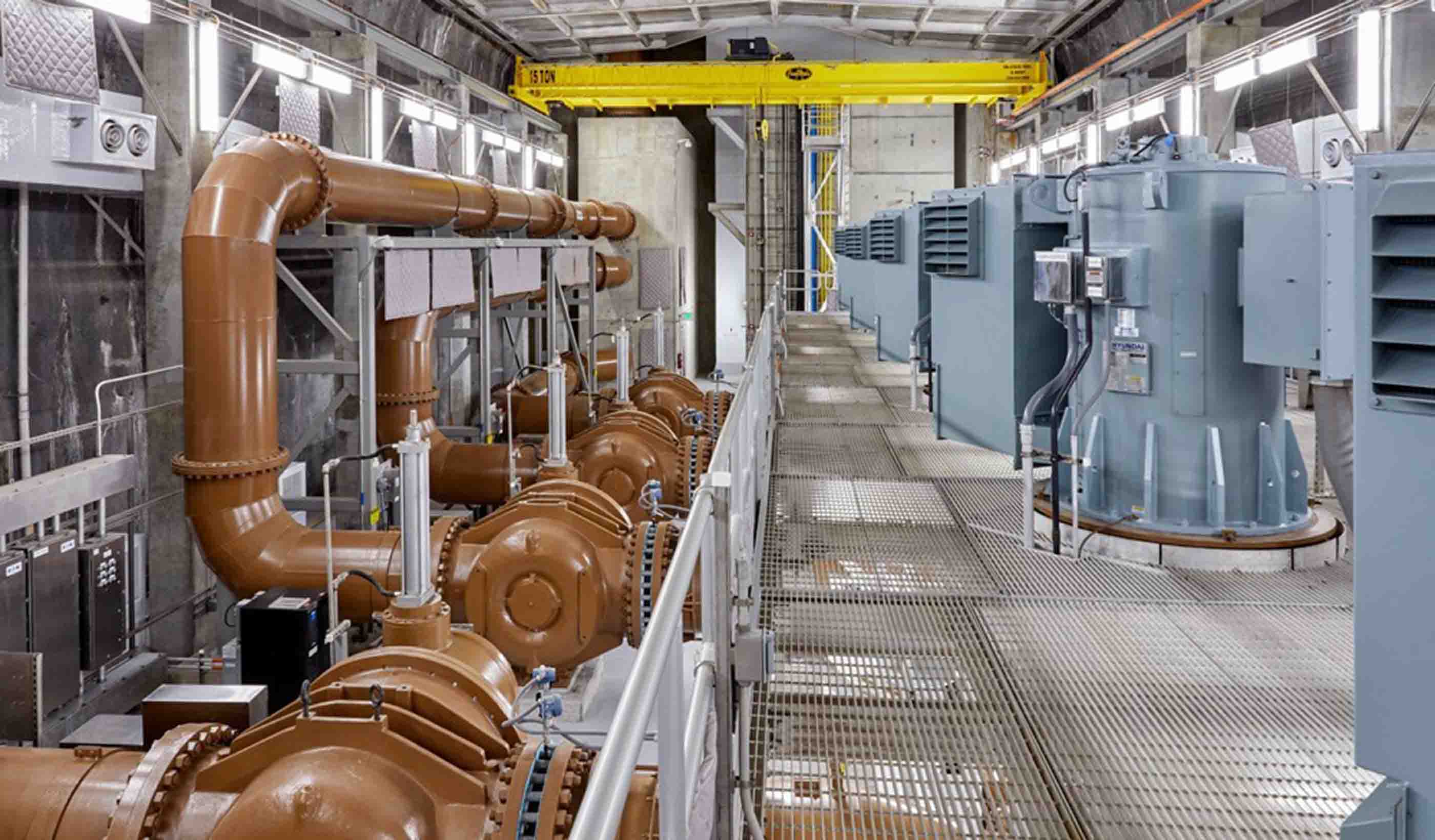

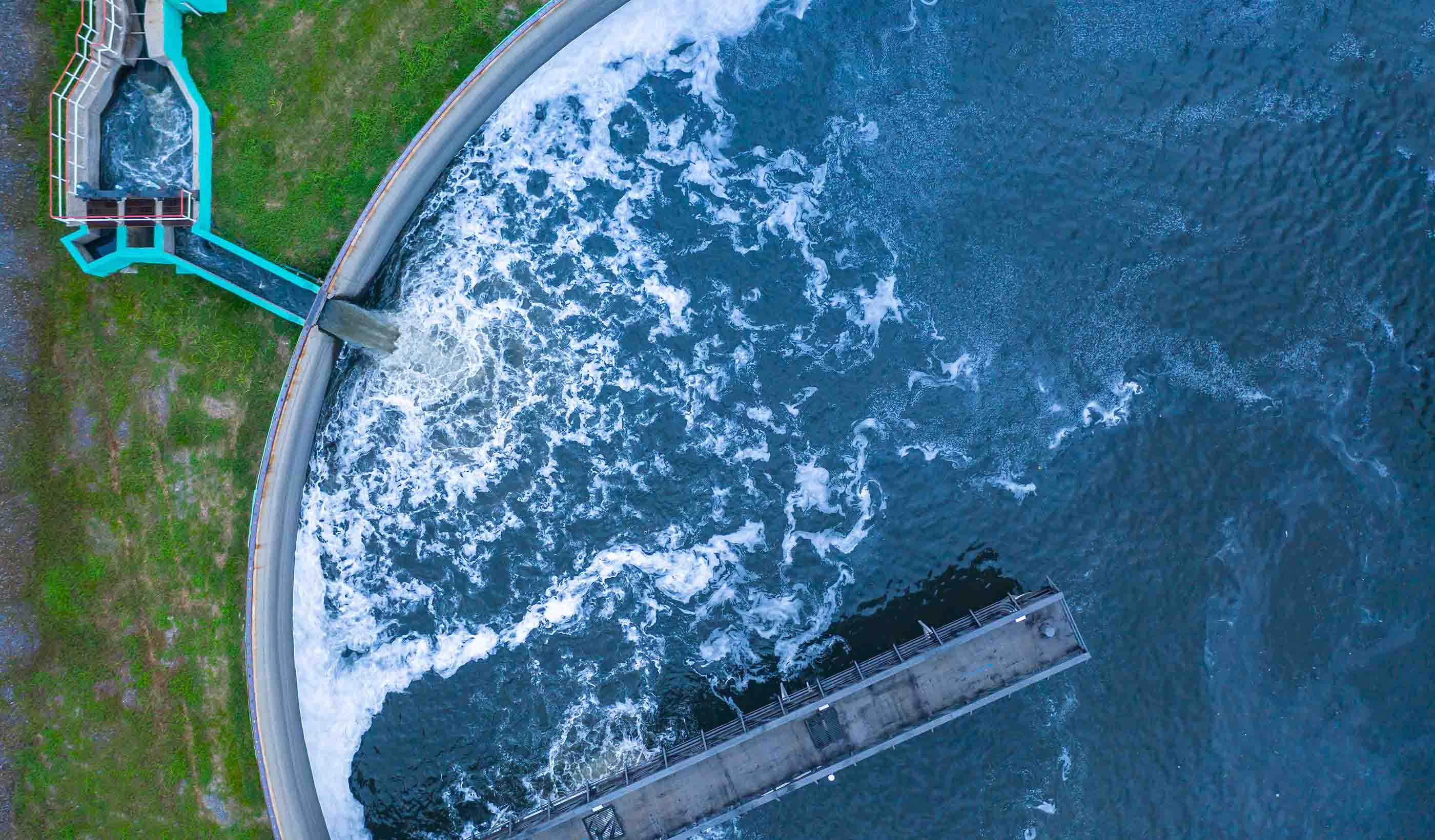

Blog Post Why update water automation systems? The hidden costs of legacy operational technology

-

Video Shaping a cleaner future through better air quality monitoring

-

Webinar Recording Cyber attack on water systems: How to thwart hackers and keep the water flowing

-

Blog Post How Generation Alpha’s expectations of higher education will transform college design

-

Blog Post Q&A: What is reality capture? How can it transform digital archaeology and other sectors?

-

Podcast Design Hive: Derreck Travis on design for career and technical education (CTE) buildings

-

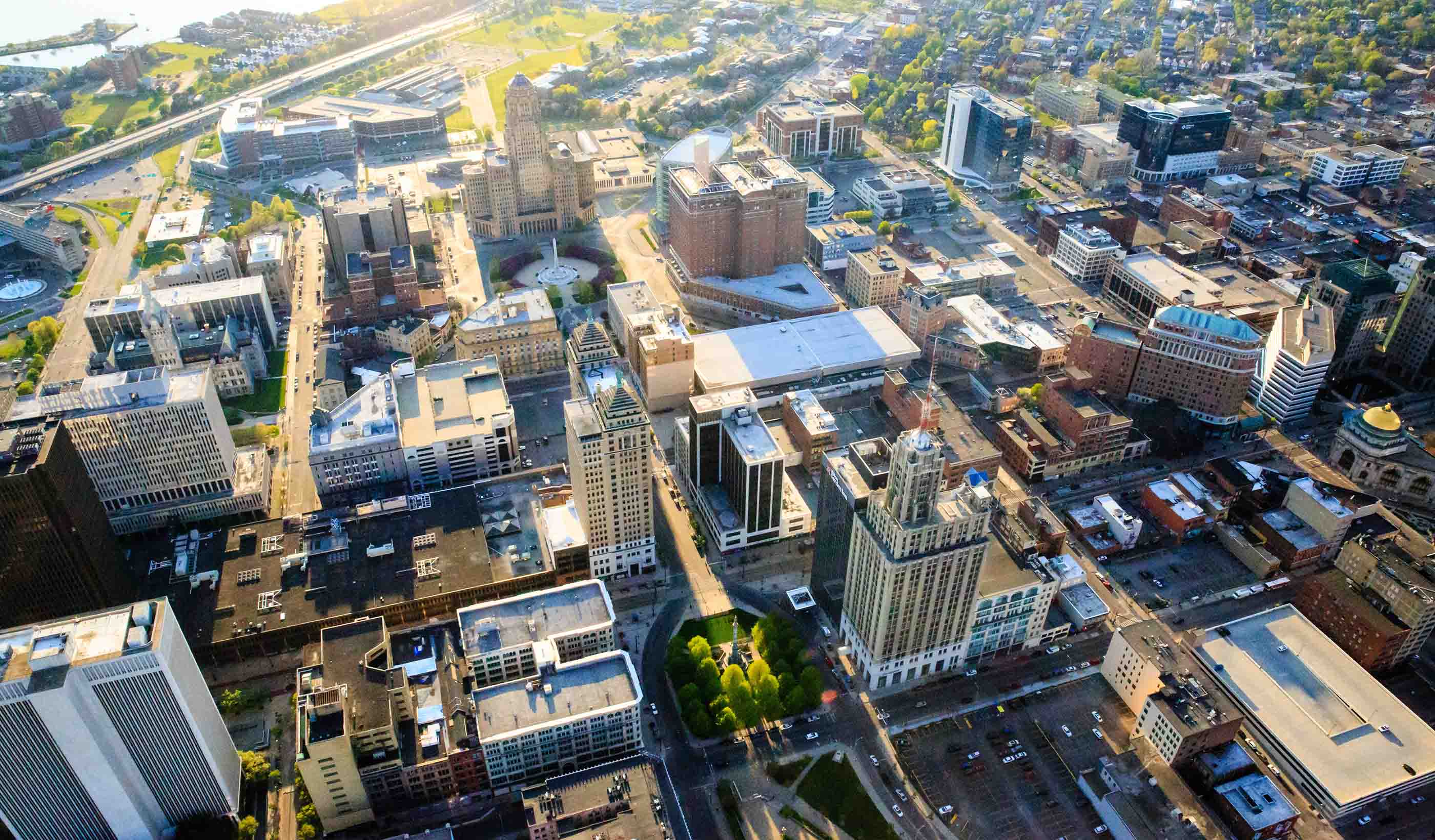

Published Article Protecting Buffalo’s freshwater future

-

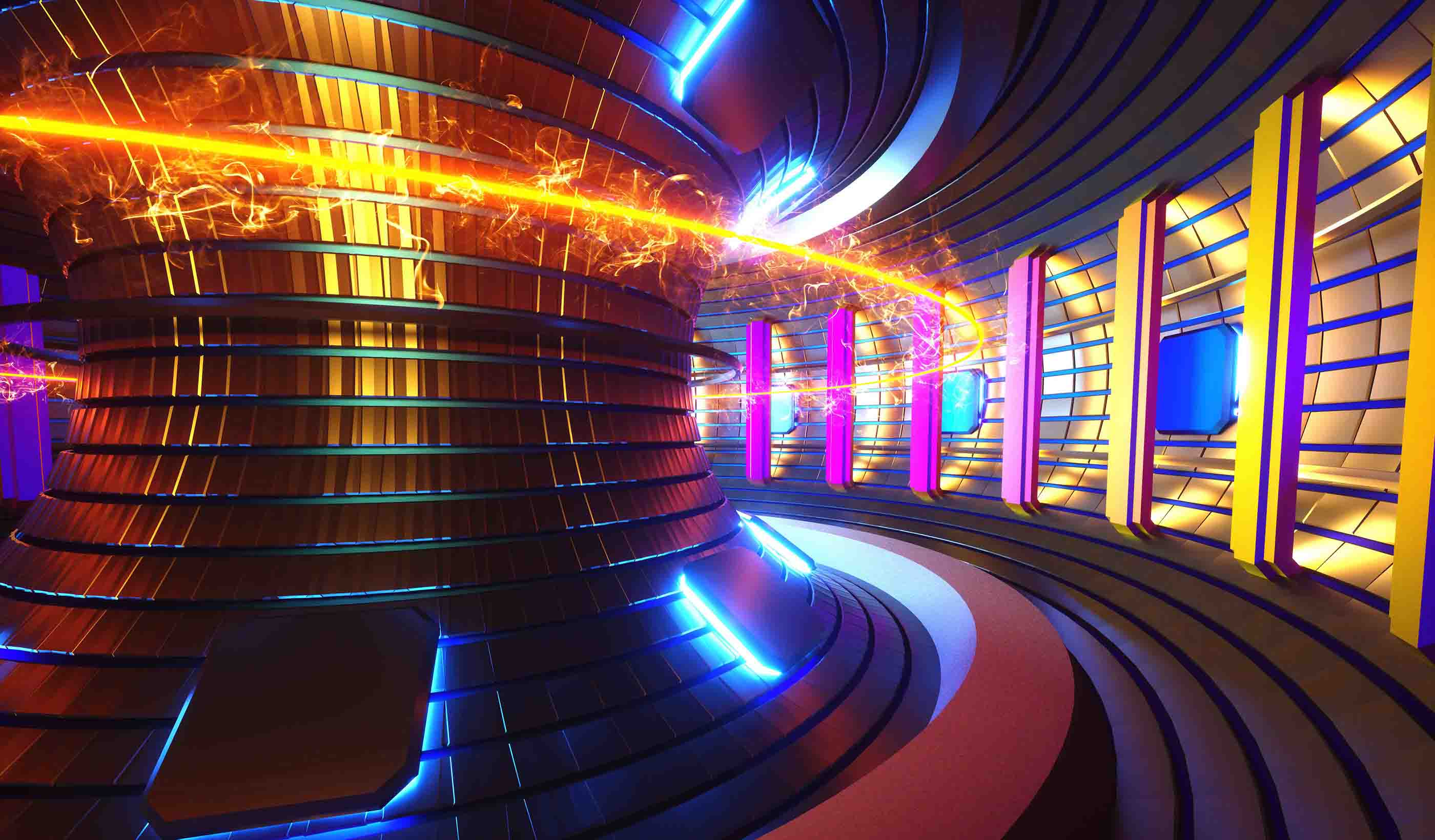

Blog Post Pairing small modular reactors with AI data centers

-

Blog Post LEED v5: What does the updated sustainability standard mean for design?

-

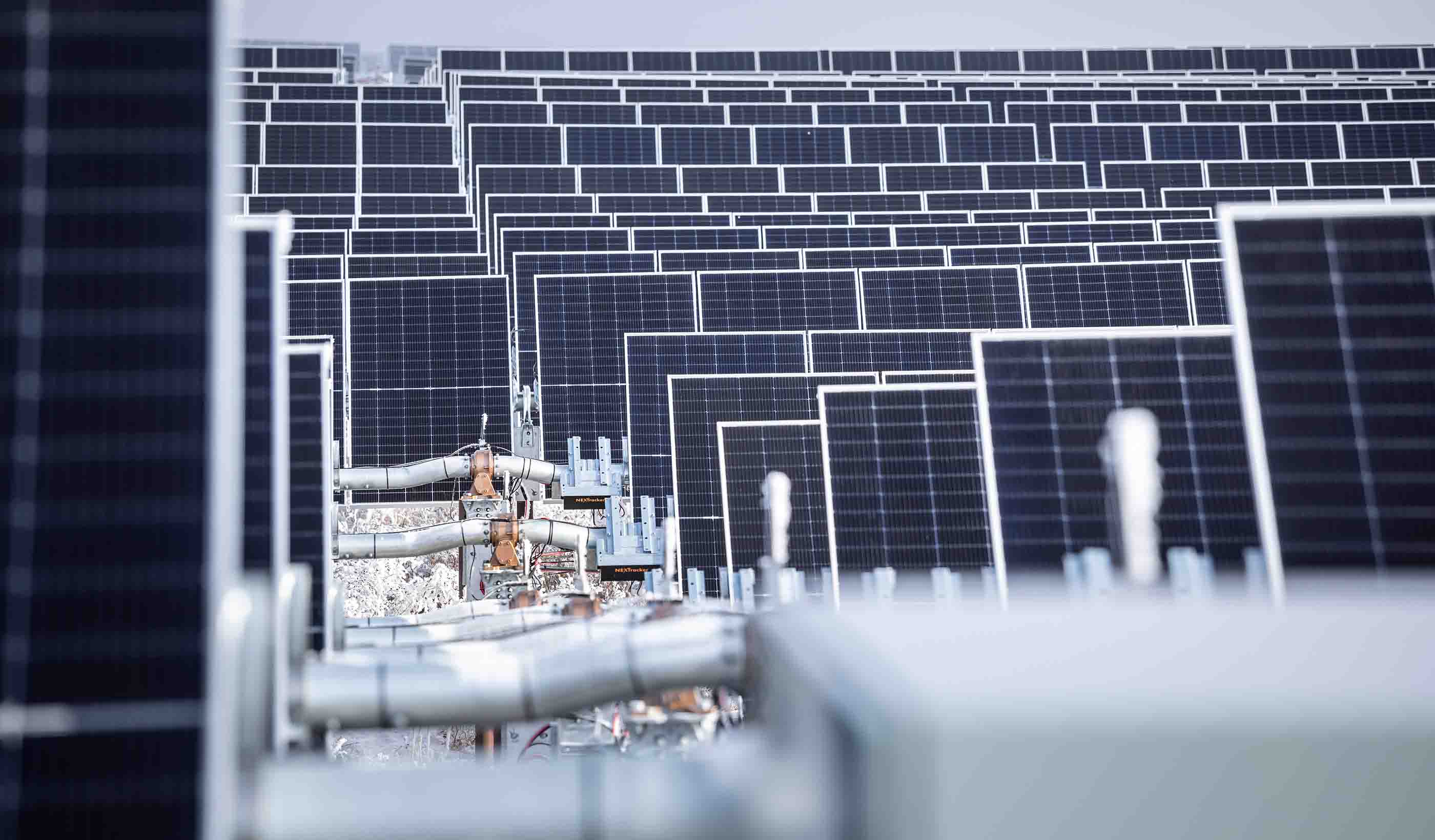

Published Article Implications of solar facilities on adjacent pipeline infrastructure

-

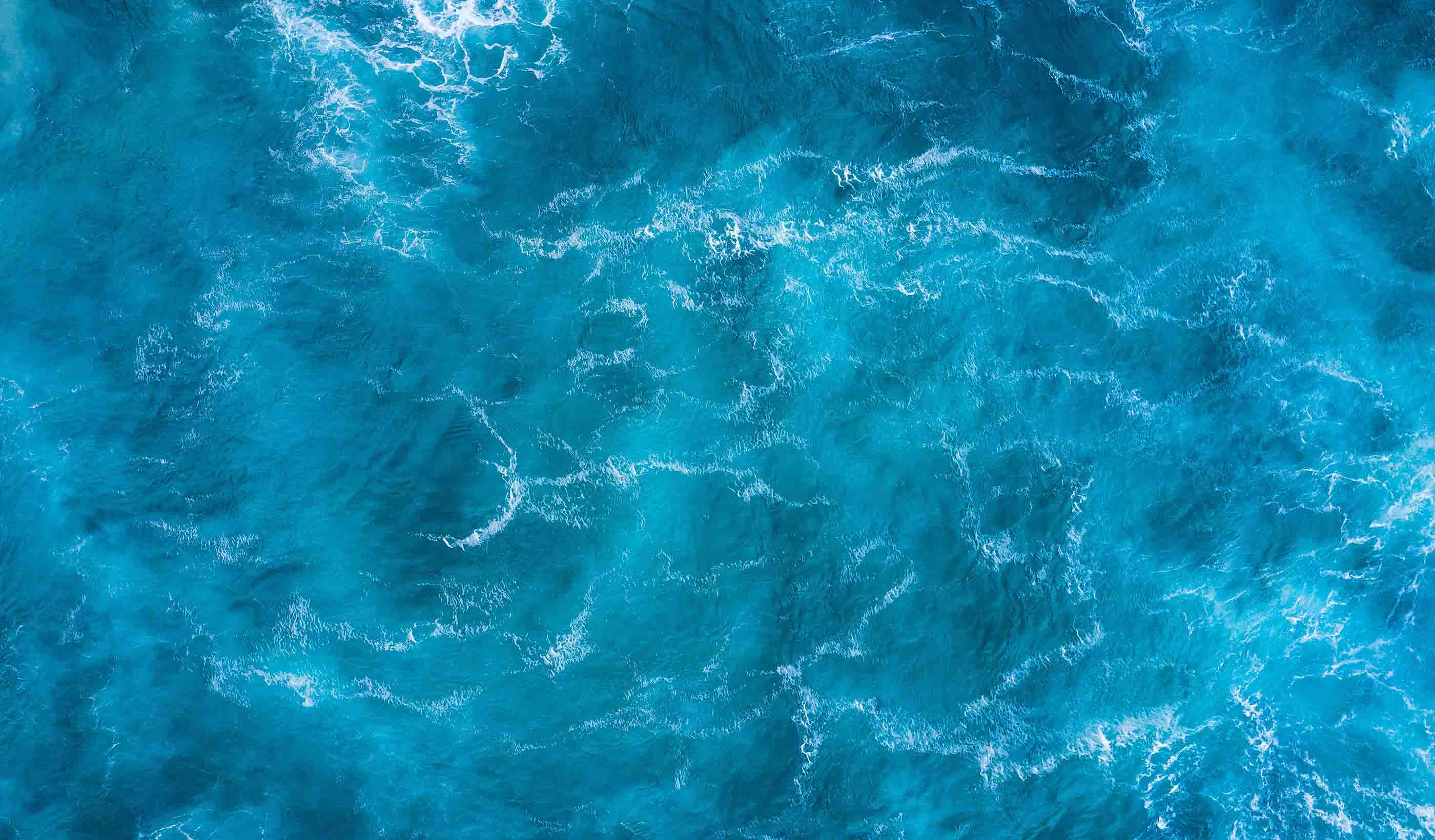

Blog Post What is bathymetric modeling? And how can it protect ecosystems while saving resources?

-

Webinar Recording Keeping your budget above water with macroeconomic trends and insights

-

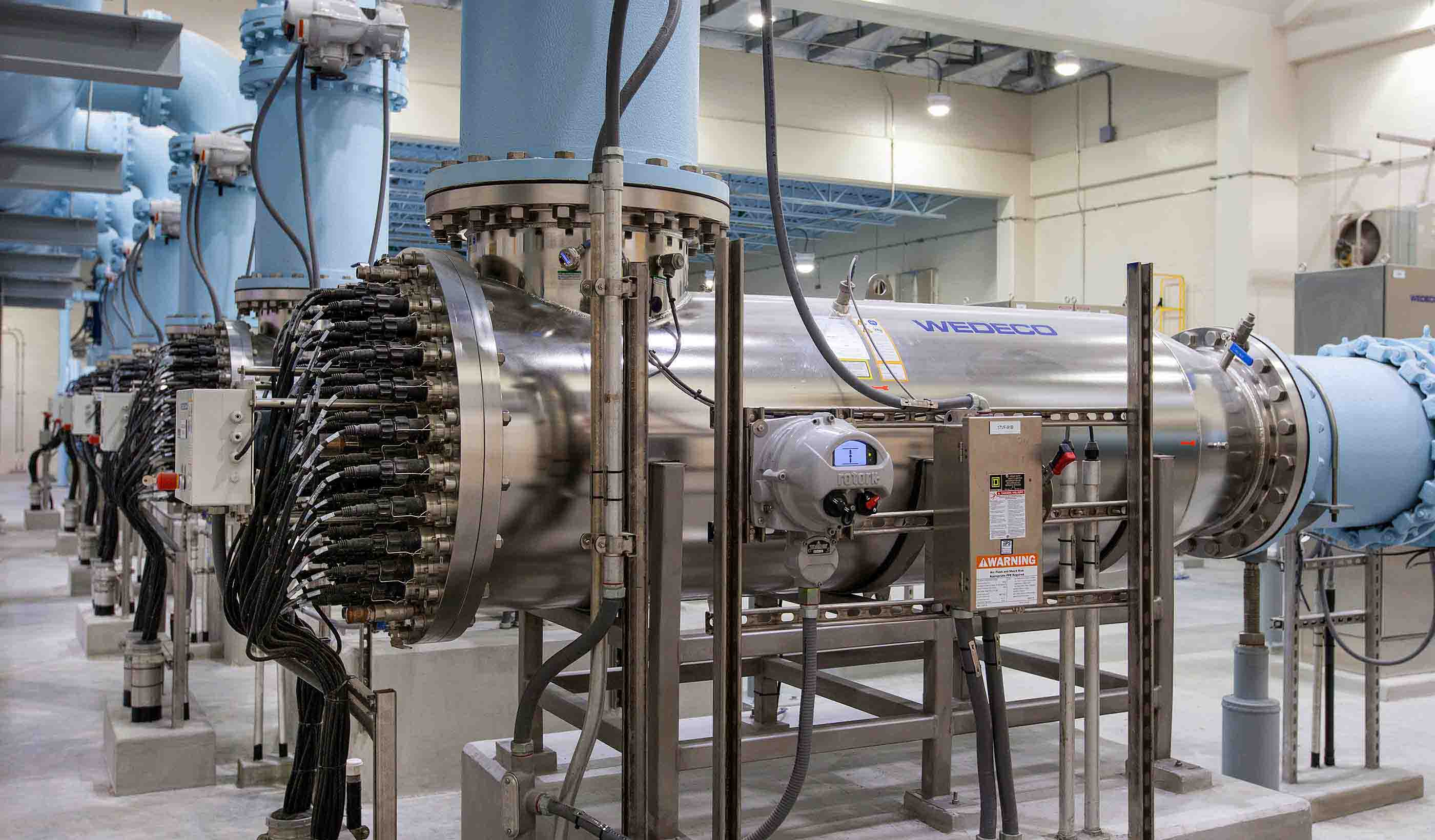

Video A vision to design and deliver a first-of-its-kind water reuse program for San Diego

-

Blog Post Q&A: Maximizing value from a building automation system

-

Published Article Demystifying water management: Finding a balance

-

Podcast Design Hive: Gwen Morgan and Stephen Parker on researching sensory room design

-

Blog Post Campus housing: How do designers balance privacy and experience for students?

-

Video Reimagining resilience starts with the heart of community

-

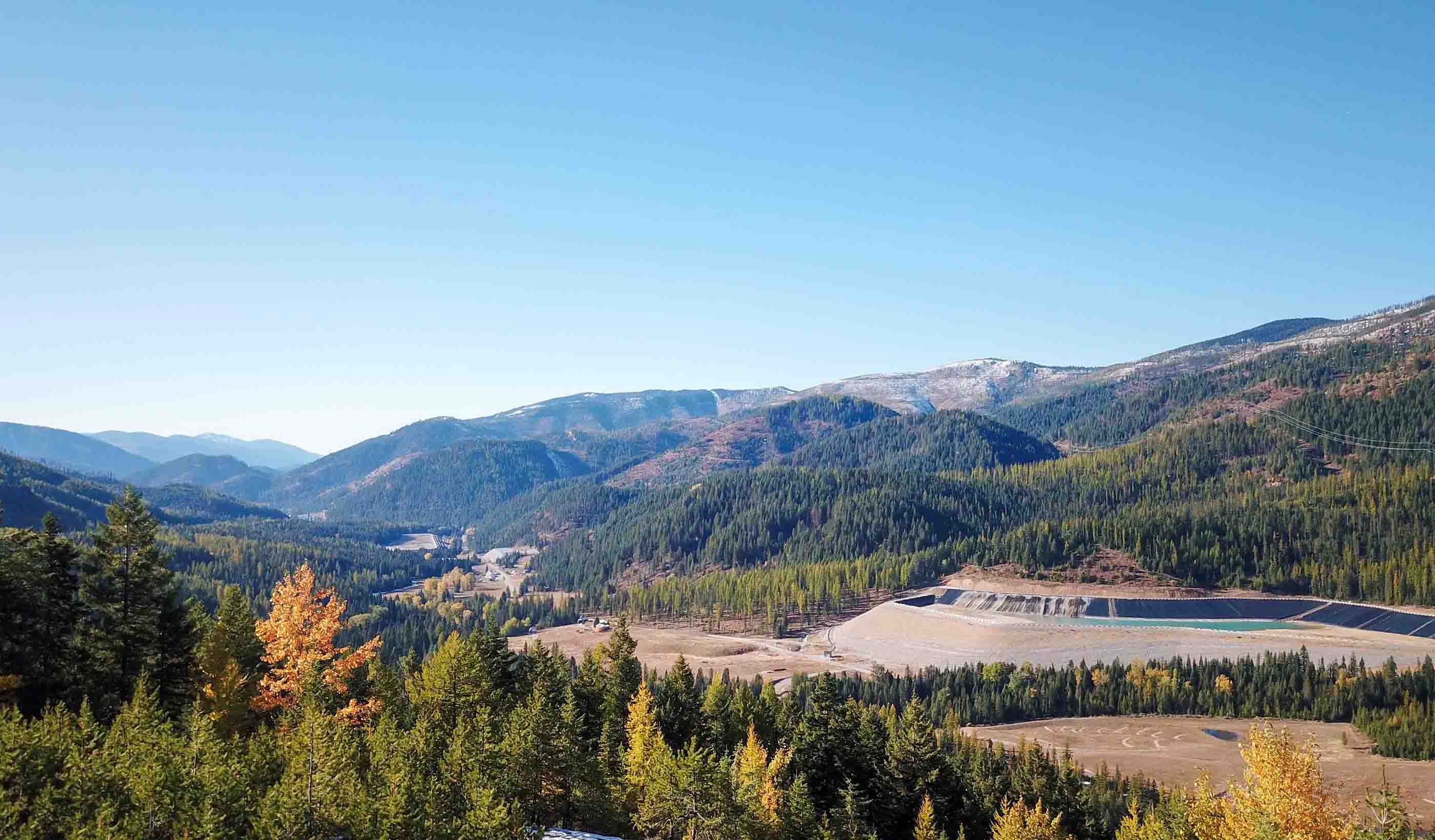

Video Transforming a Colorado mine into community green space

-

Blog Post How does a transit agency roll out a battery electric bus fleet? Here are the steps

-

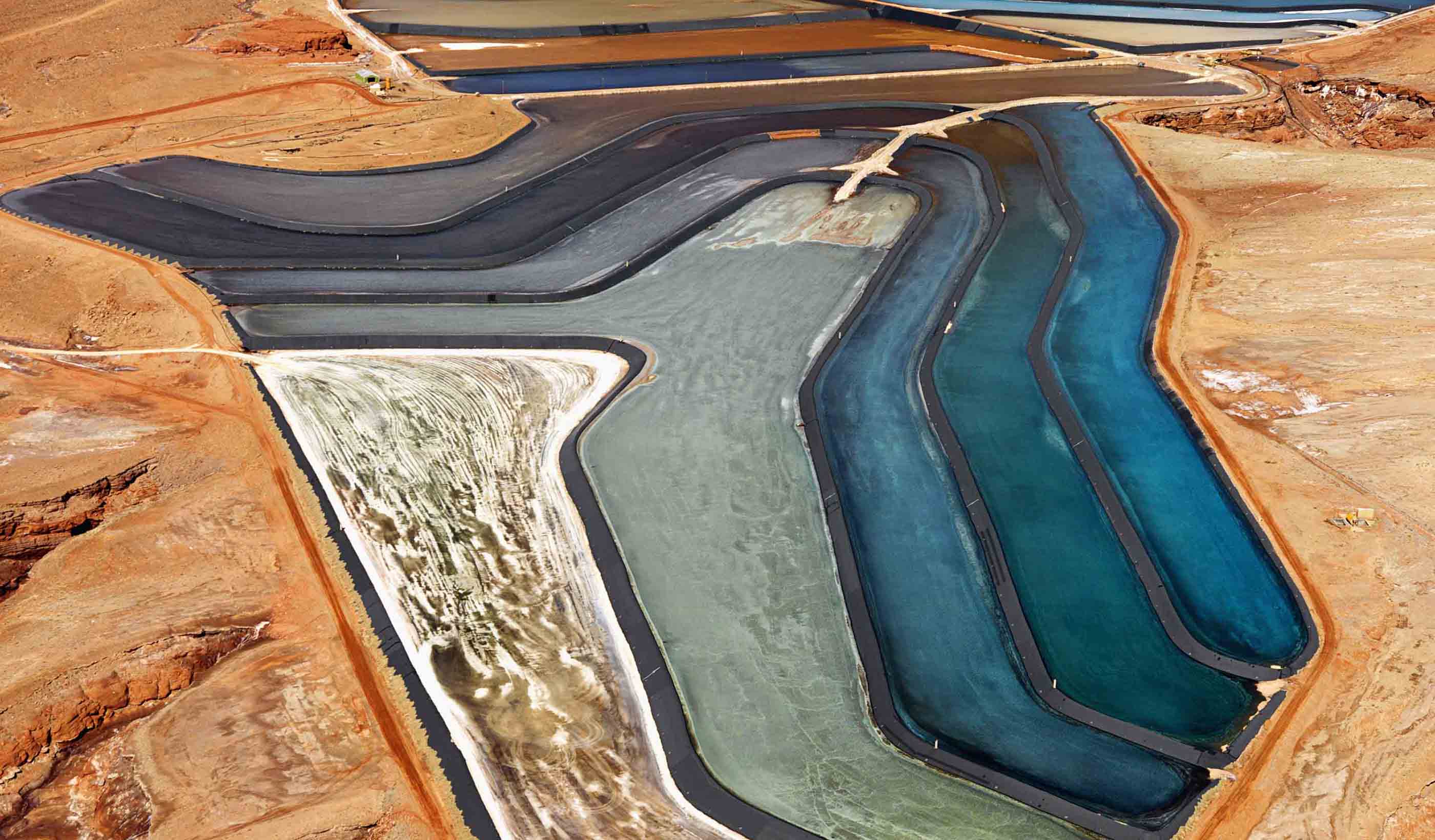

Published Article A shifting landscape in the mining industry

-

Published Article Powering the future: Canada’s role in the critical minerals race

-

Blog Post Industrial cold storage: How tailored solutions can unleash innovation

-

Video CSRD and sustainability reporting: Strengthening risk management and maximizing impact

-

Webinar Recording Asset Management: Roadmap to risk reduction

-

Blog Post How can urban planners drive equitable planning practices in a changing landscape?

-

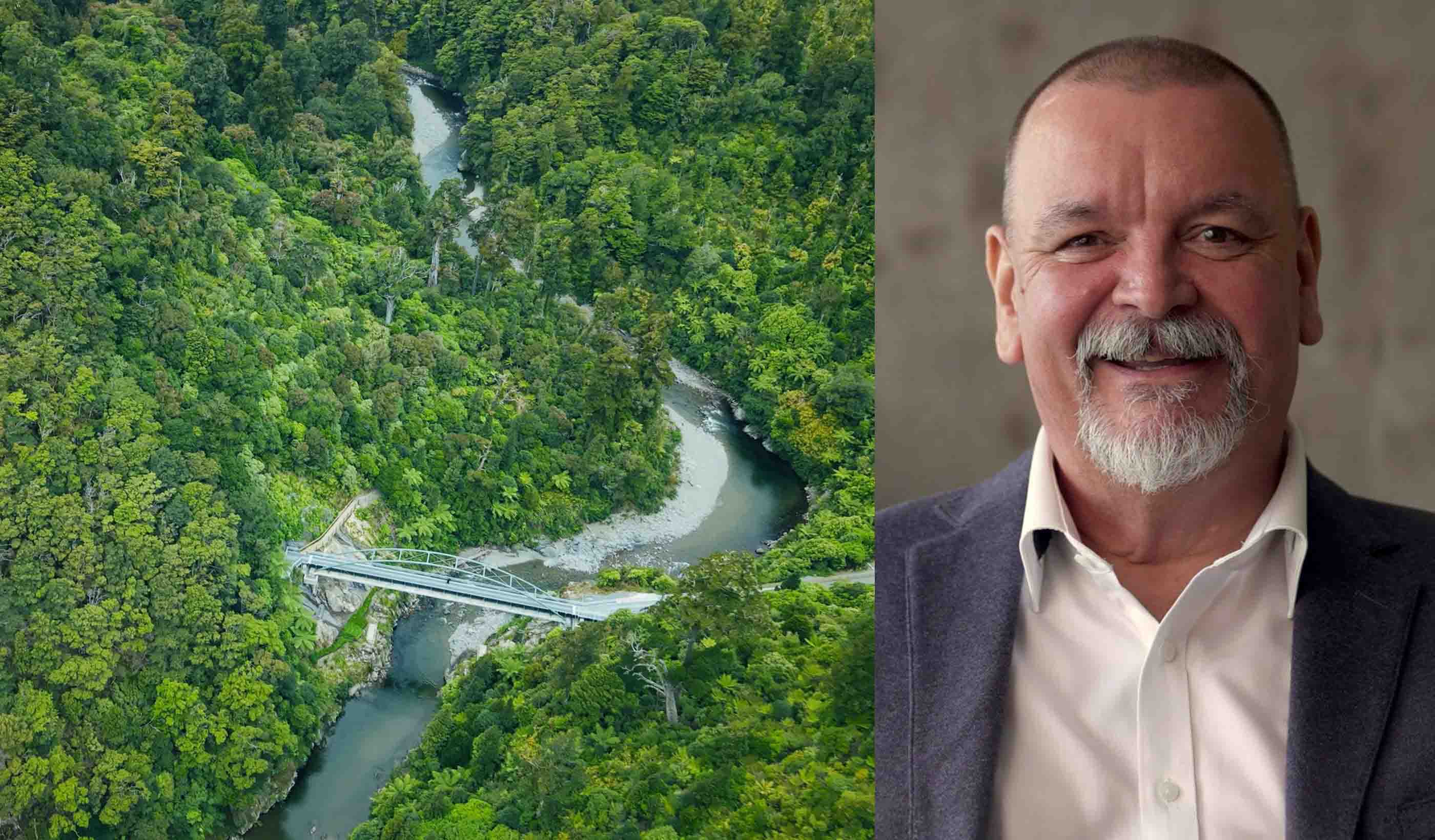

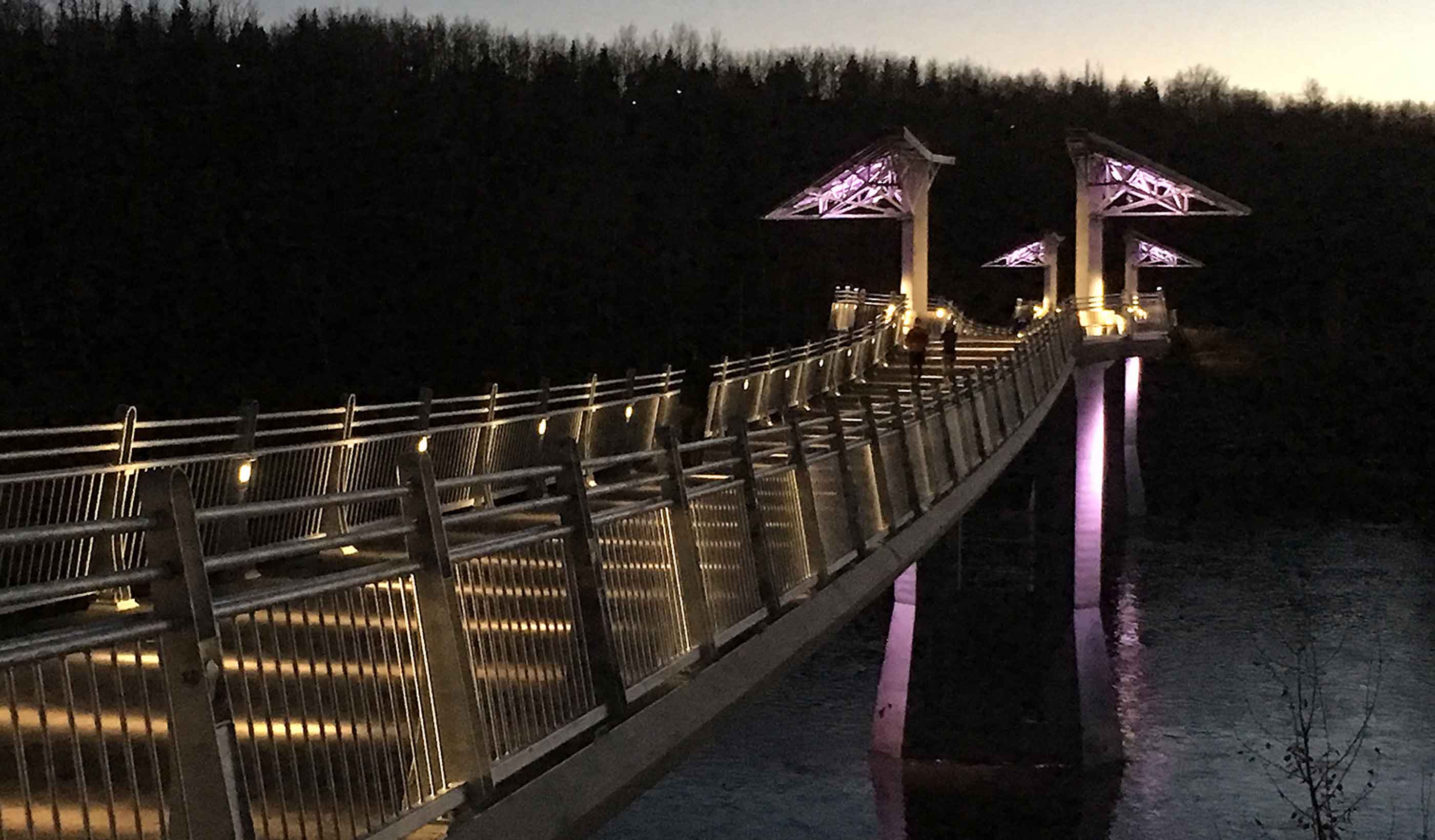

Video Kaitoke Bridge: The alchemy of location, community, and legacy

-

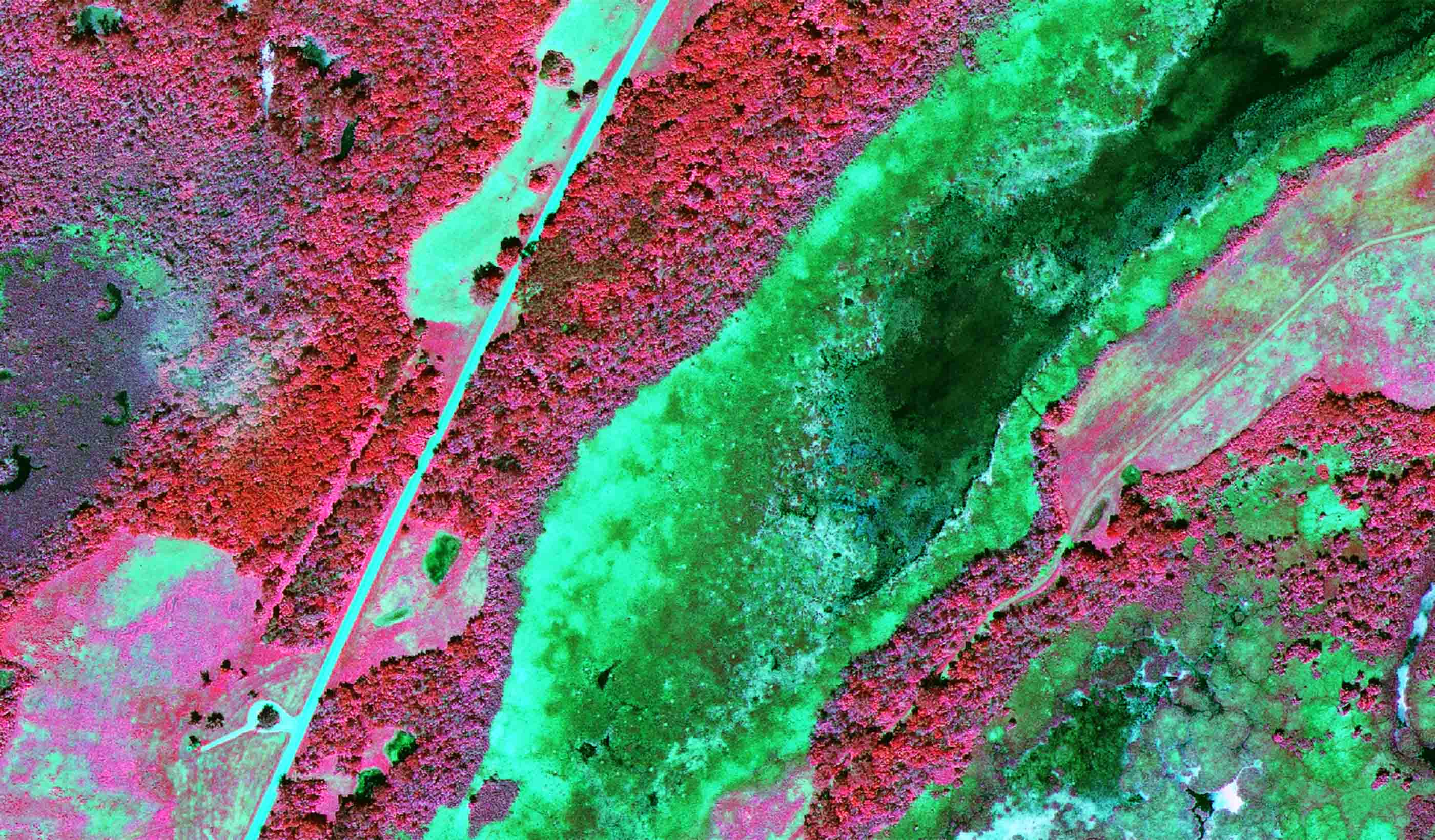

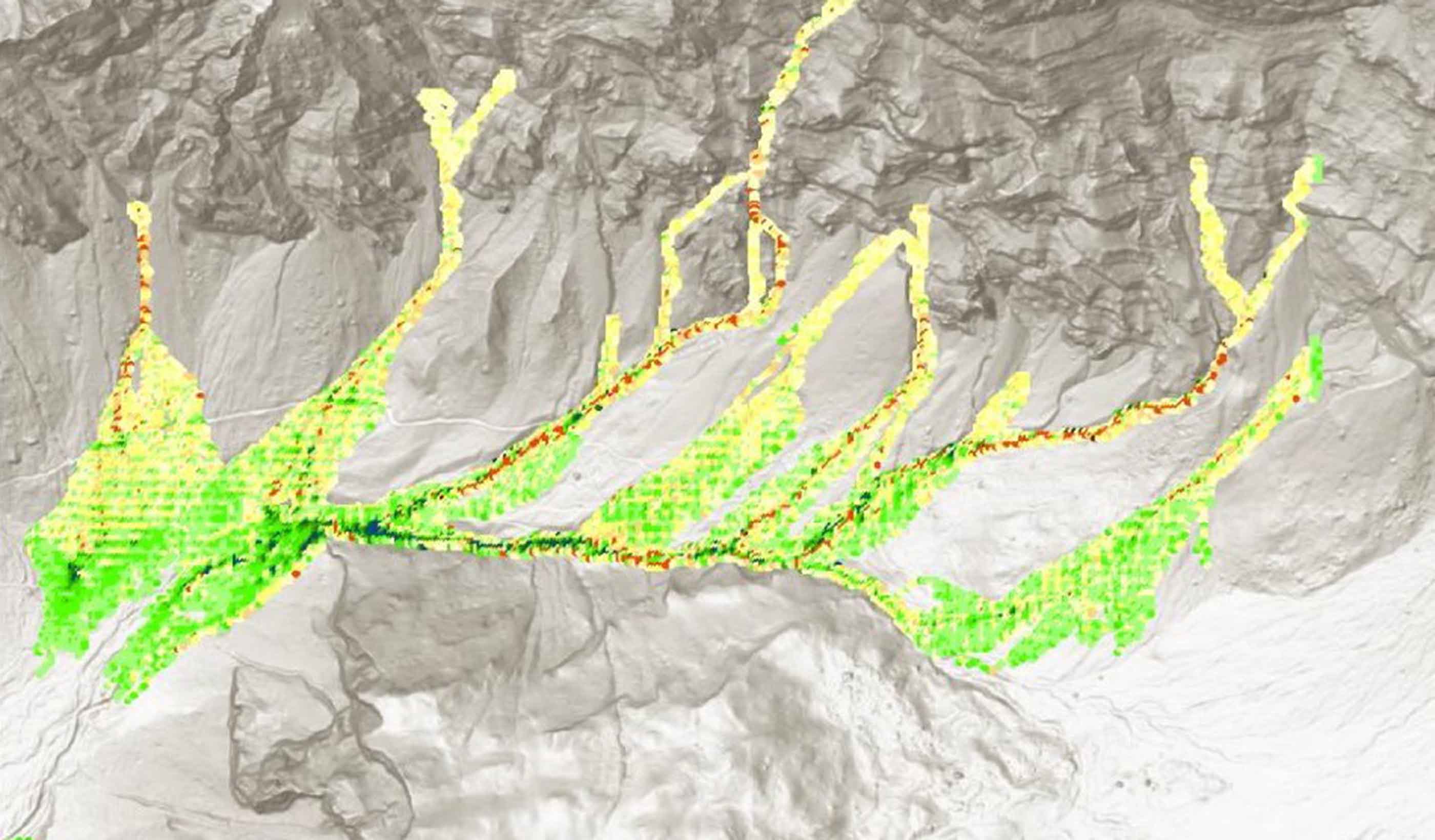

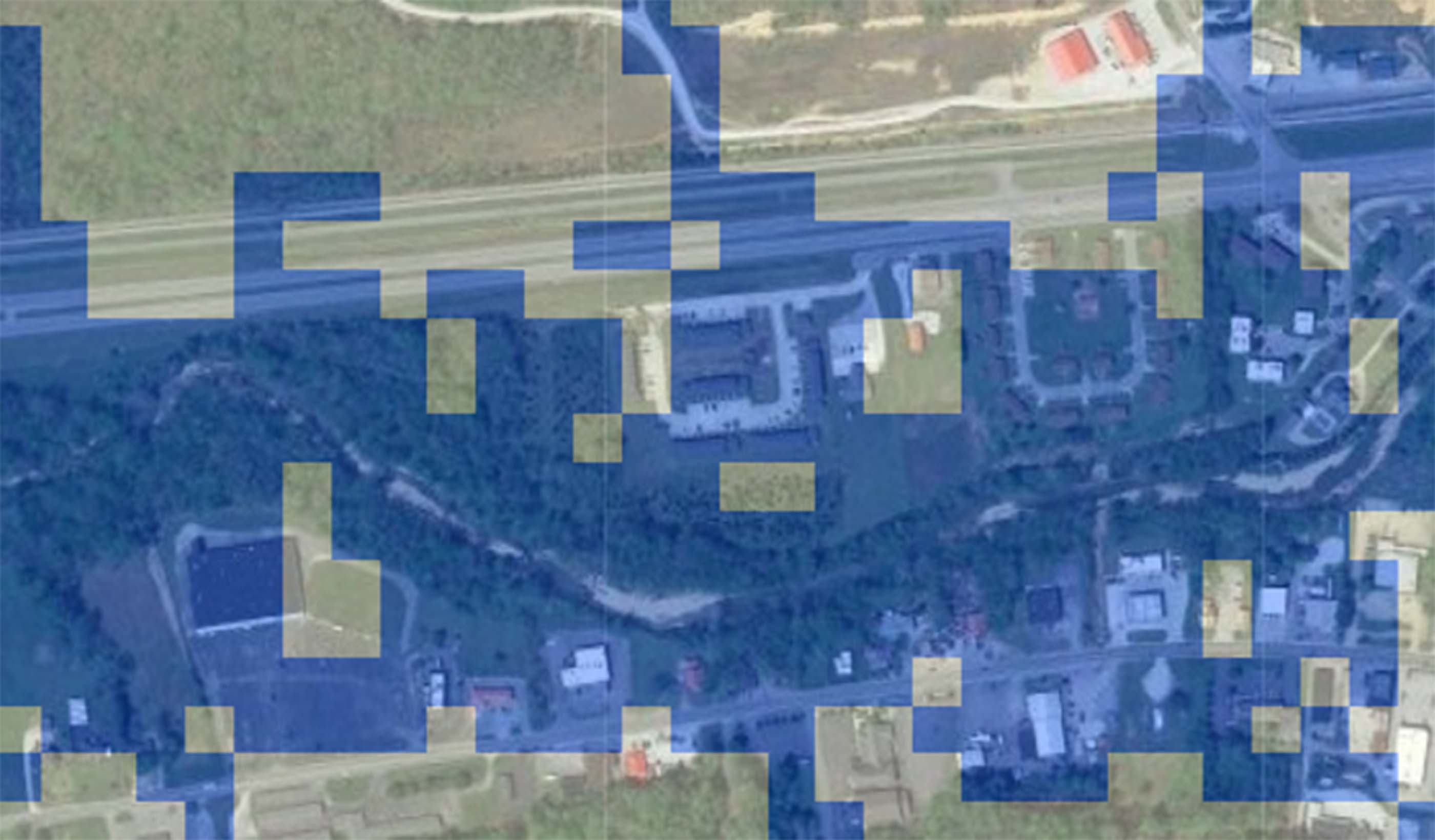

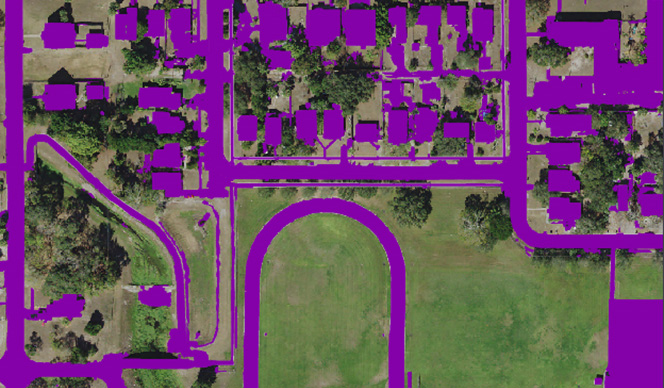

Published Article Stantec utilizes Airbus’ Pléiades to detect hazardous pipeline right-of-way encroachments

-

Blog Post Broadband fiber optic easements: 5 lessons for planning long-haul systems

-

Webinar Recording Lead and Copper Rule Improvements (LCRI) compliance: Navigating regulatory uncertainty

-

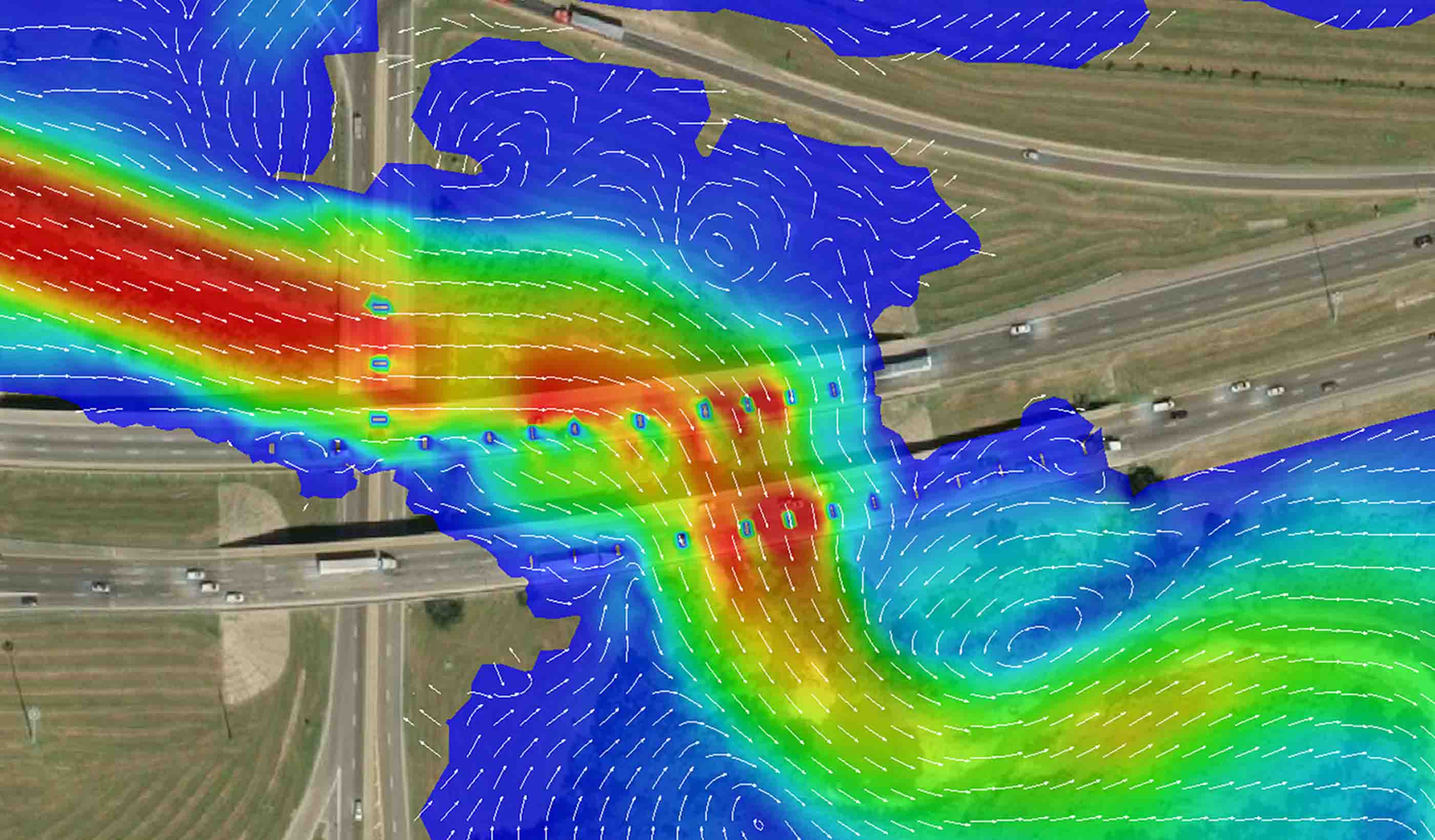

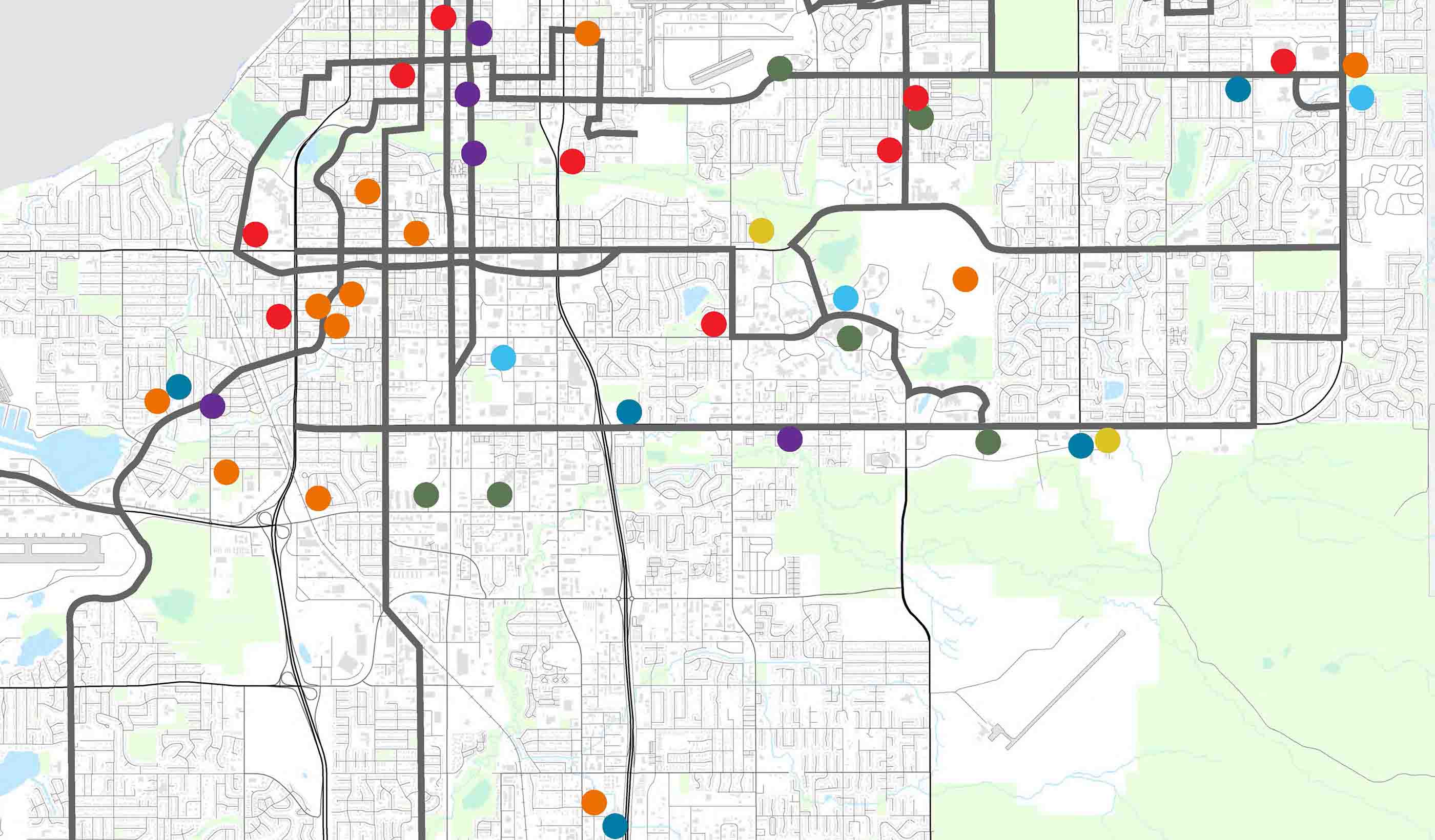

Published Article Seeing—more clearly—where stormwater floods Denver

-

Published Article Consultant Q&A: Ryan White on regulation, funding, and community-centered solutions

-

Blog Post We’re halfway through 2025. Here are 5 trends impacting the AEC world

-

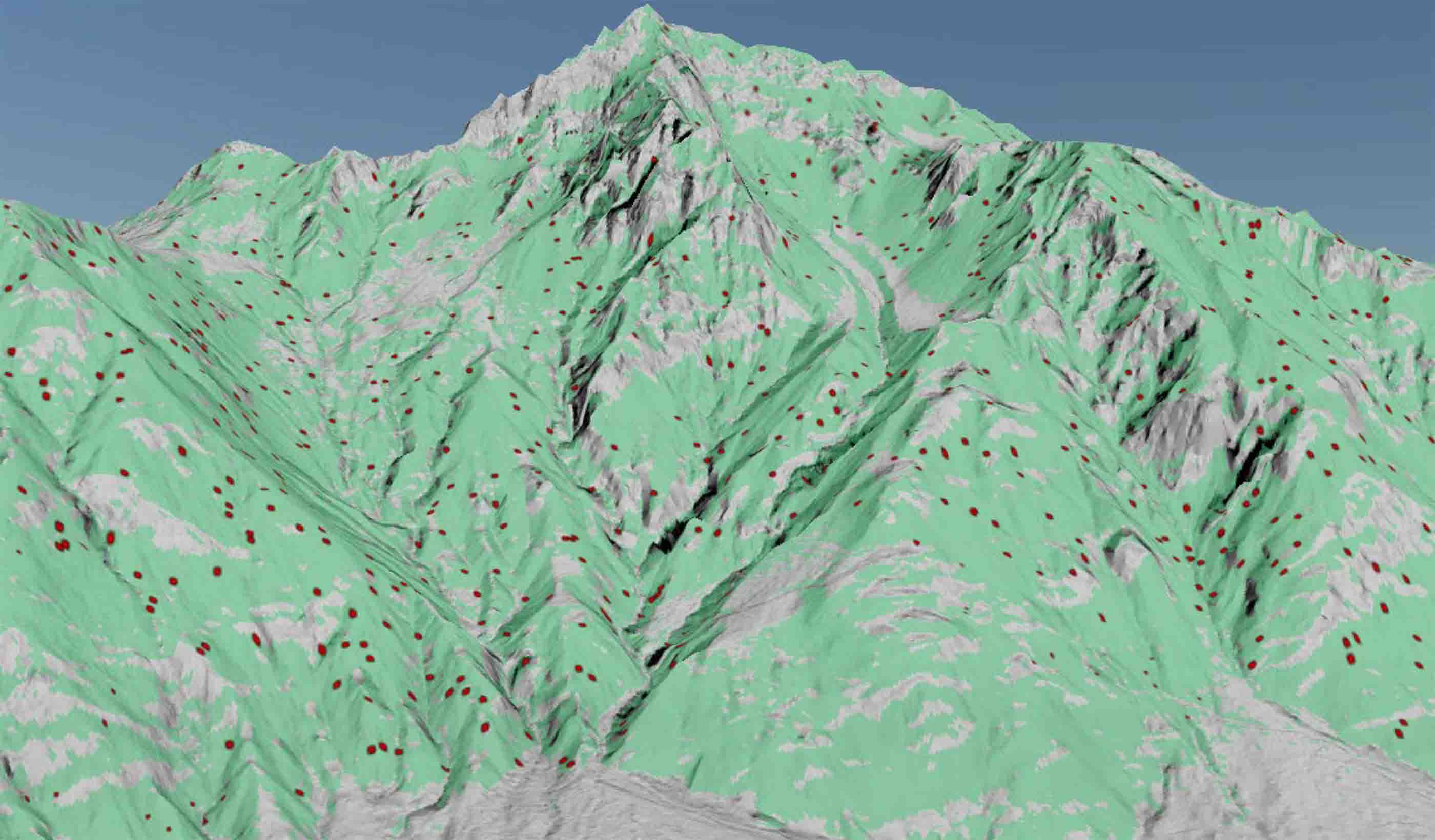

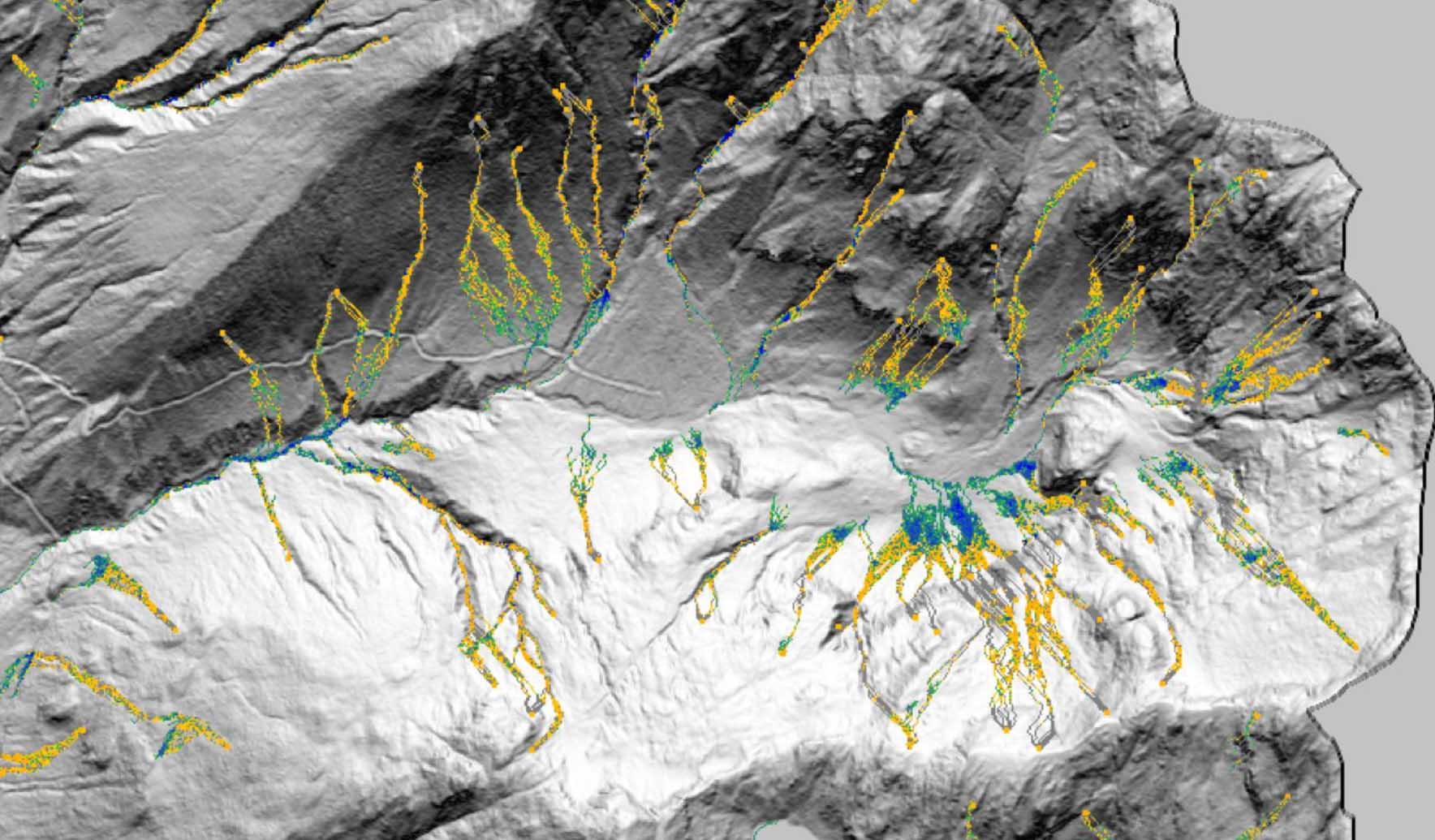

Video I’m an Innovator: Using technology to help communities predict debris flows

-

Published Article How to eliminate ground loops in building electrical systems

-

Publication Design Quarterly Issue 25 | Regrowth and renewal

-

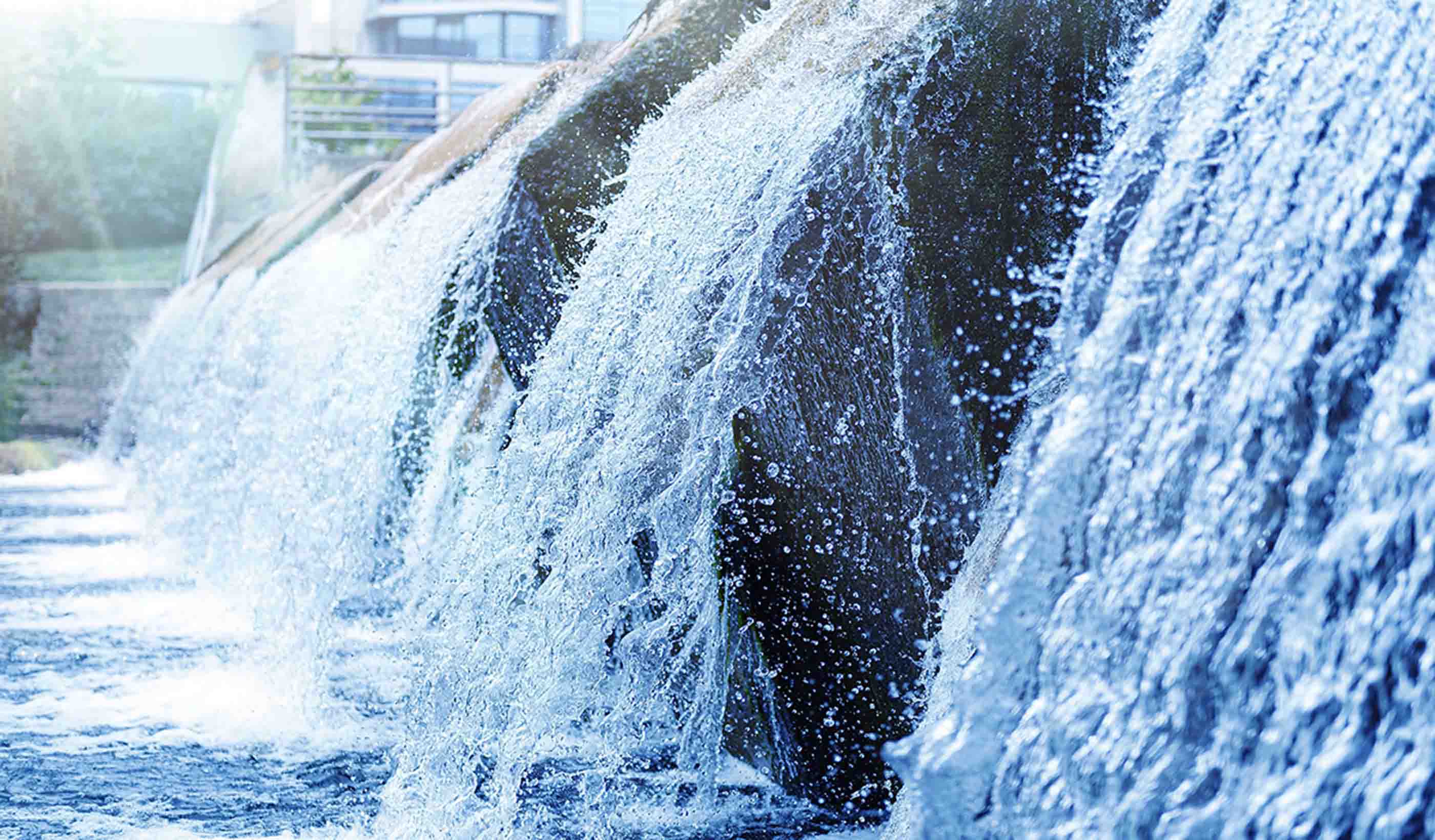

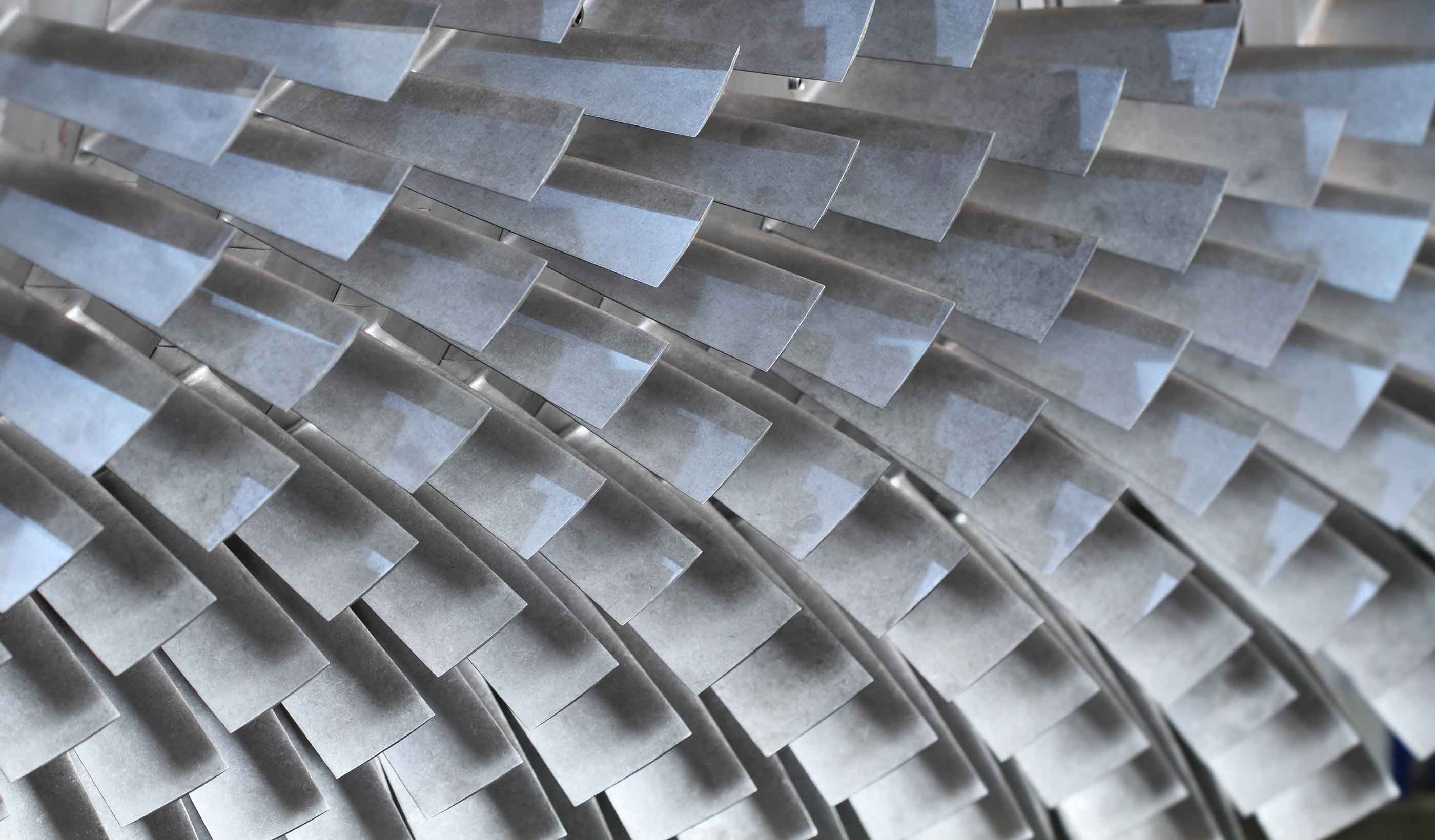

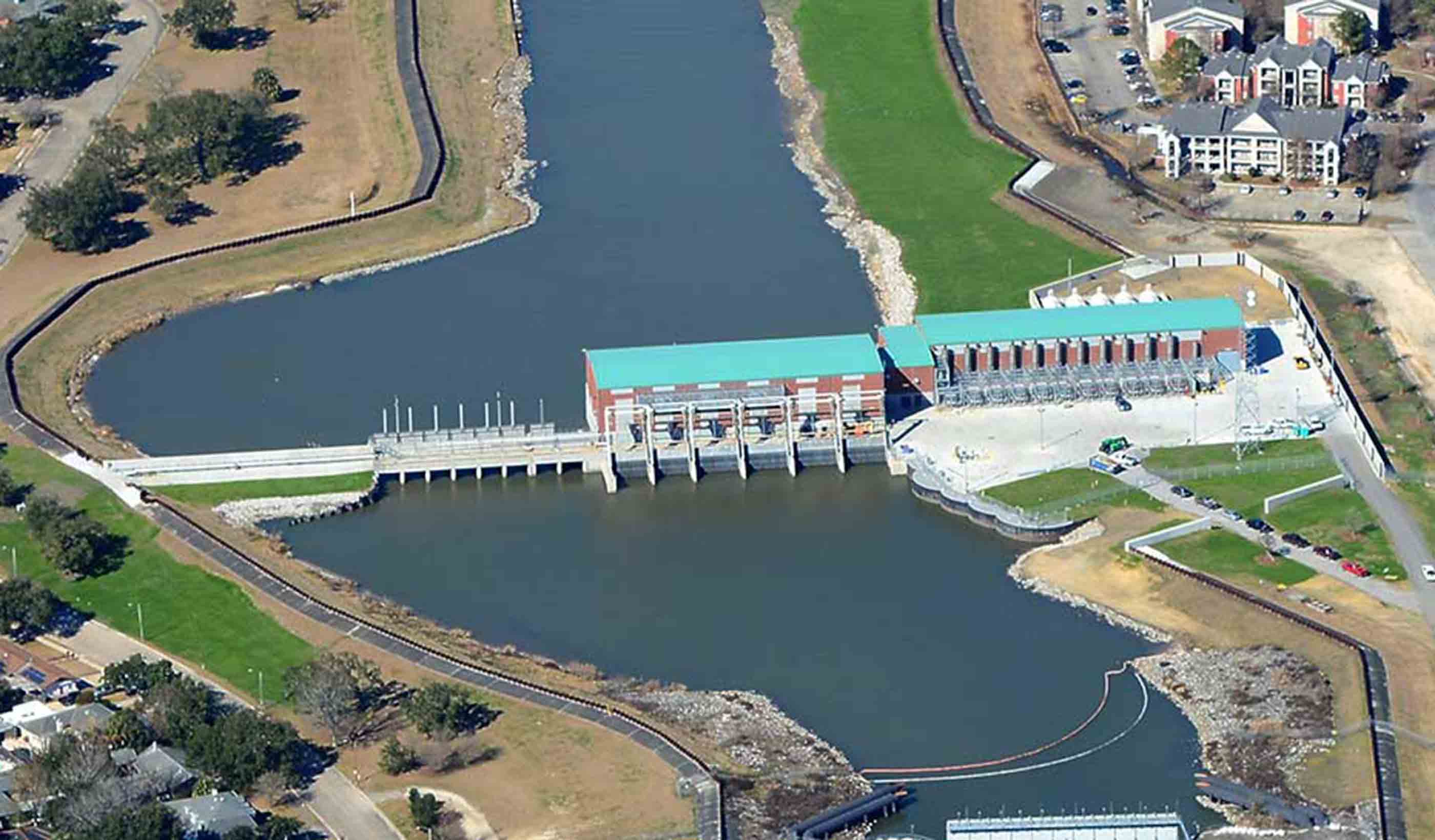

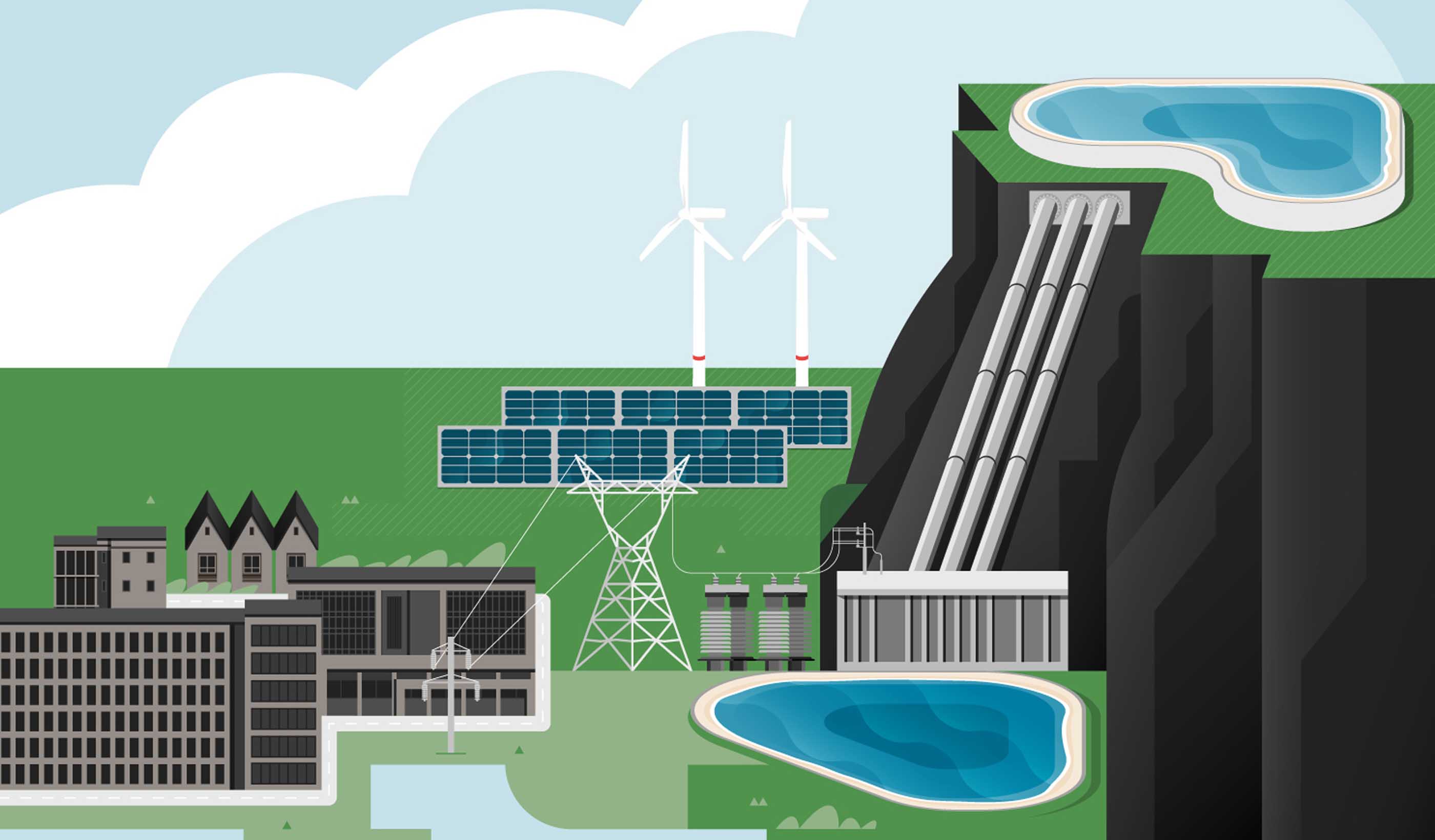

Blog Post Beyond clean energy: The many benefits of hydropower

-

Video The power answer: Clean, stable energy in every community

-

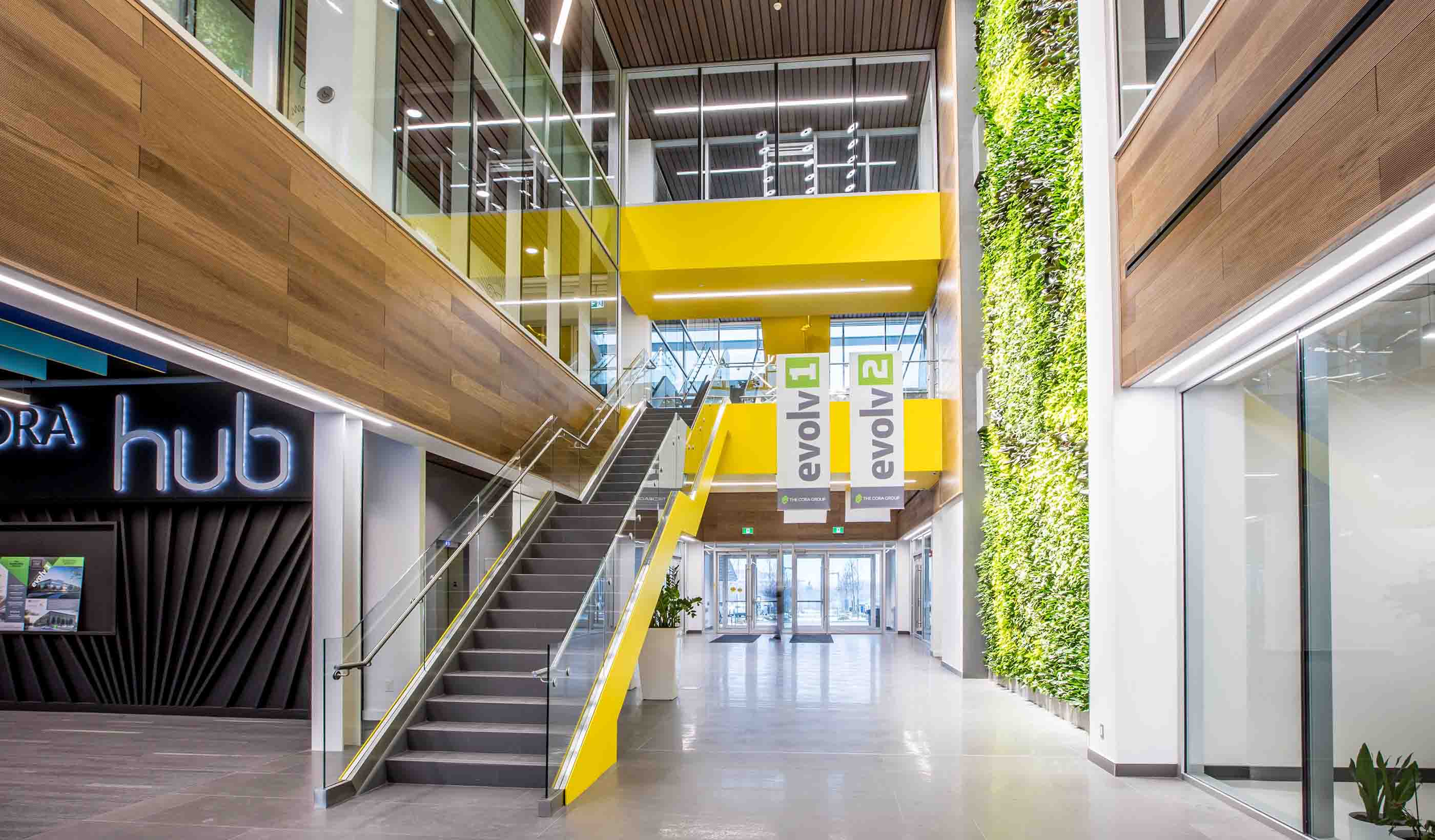

Blog Post Who needs a purpose-driven workplace? How the office can help align organizational vision

-

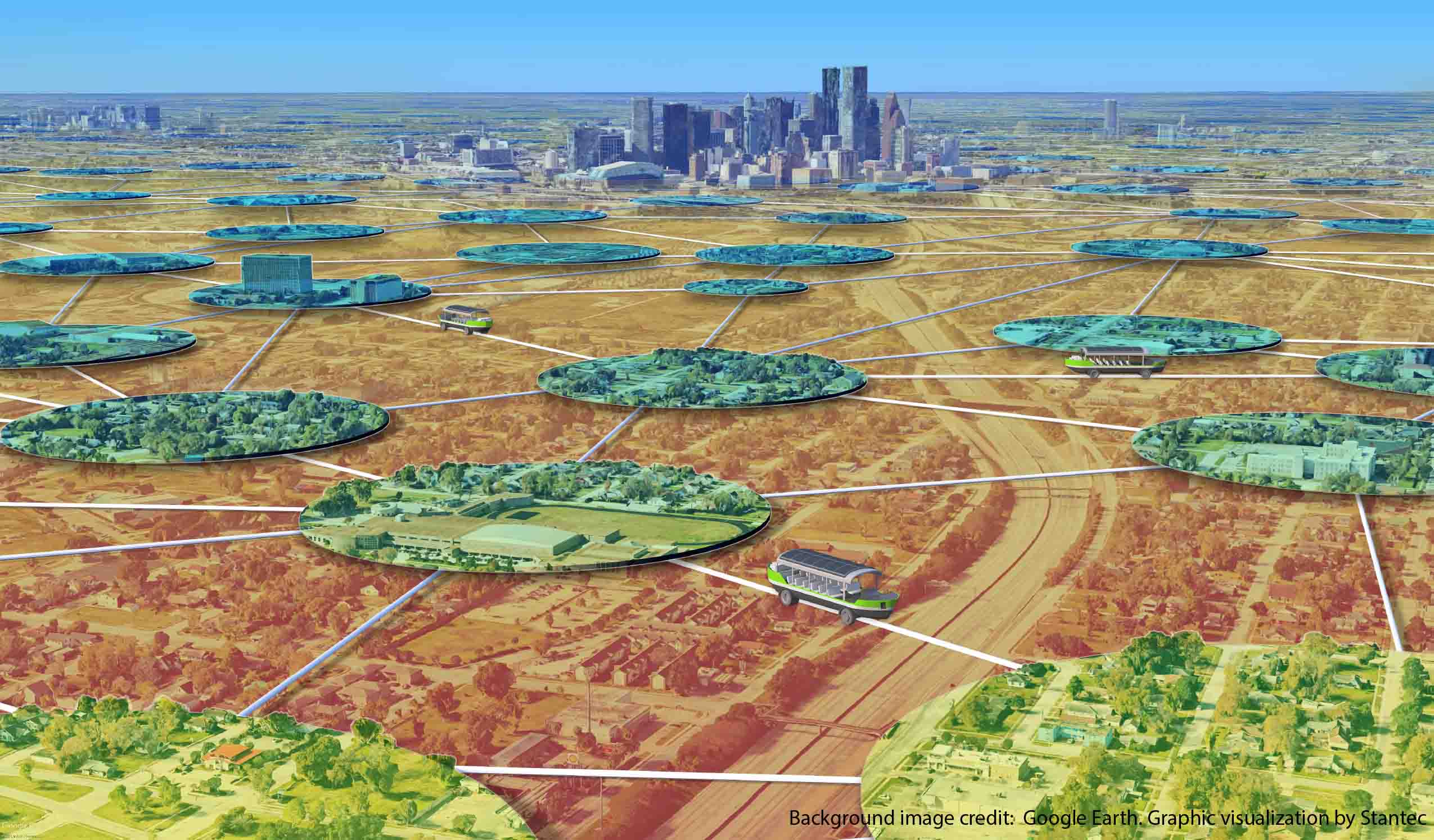

Published Article Navigating the distributed energy resources revolution

-

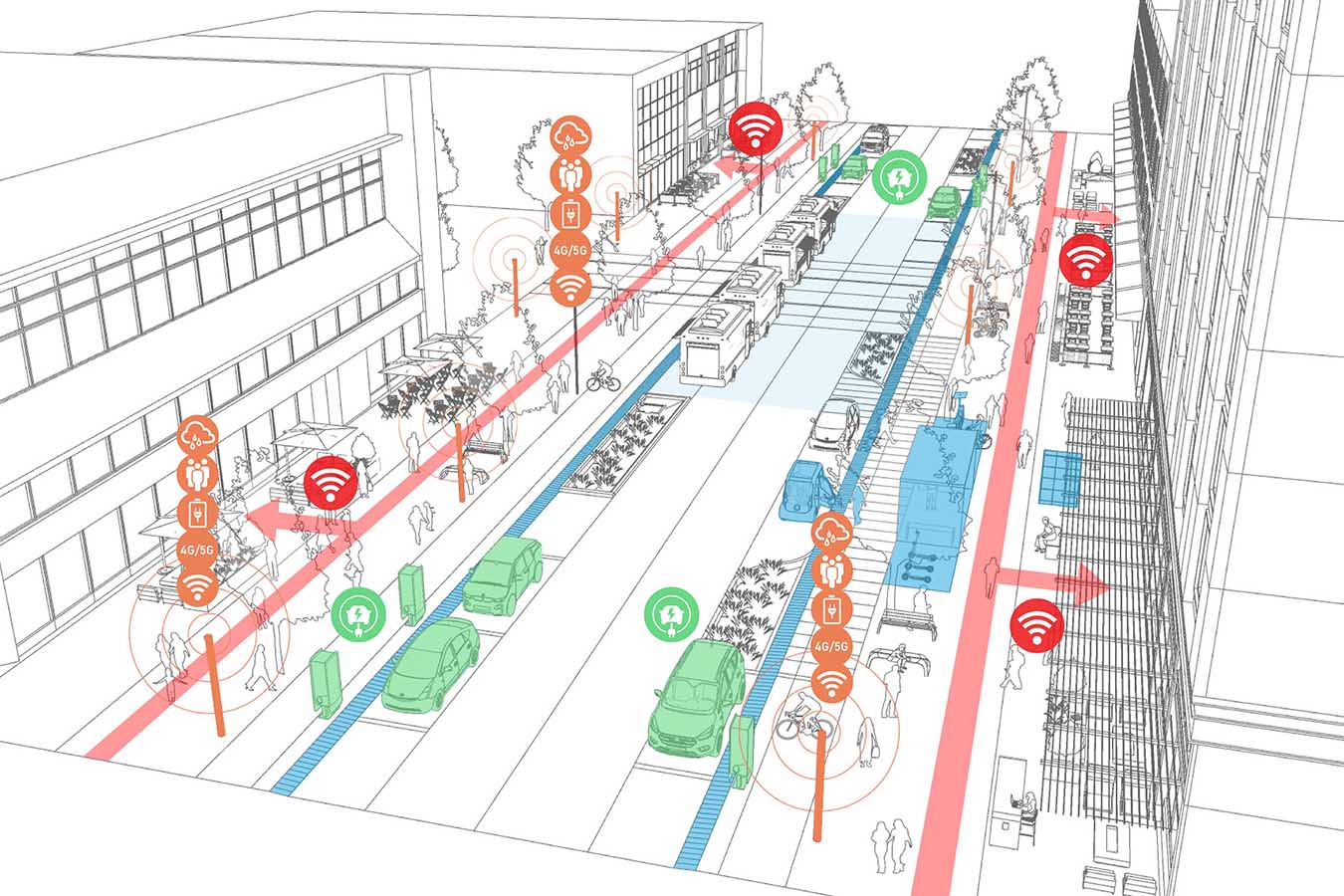

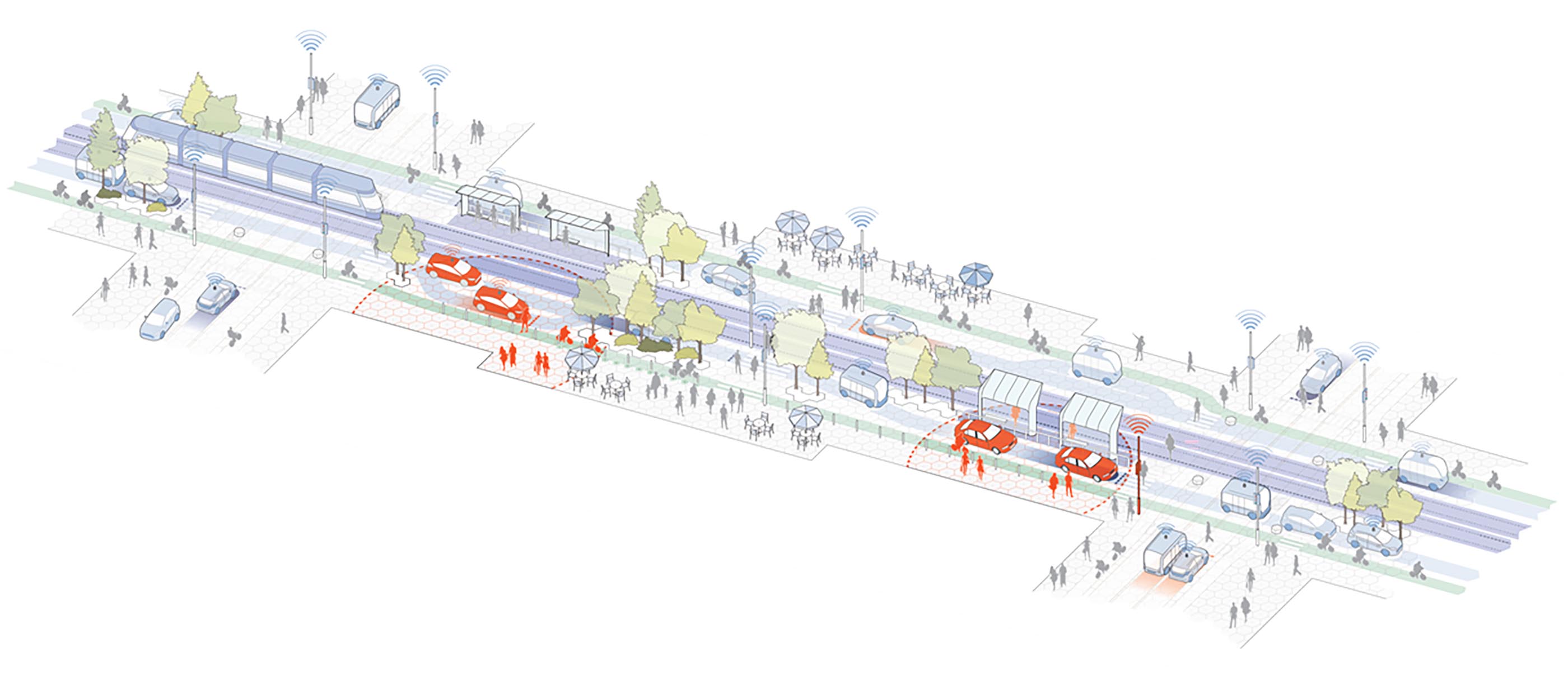

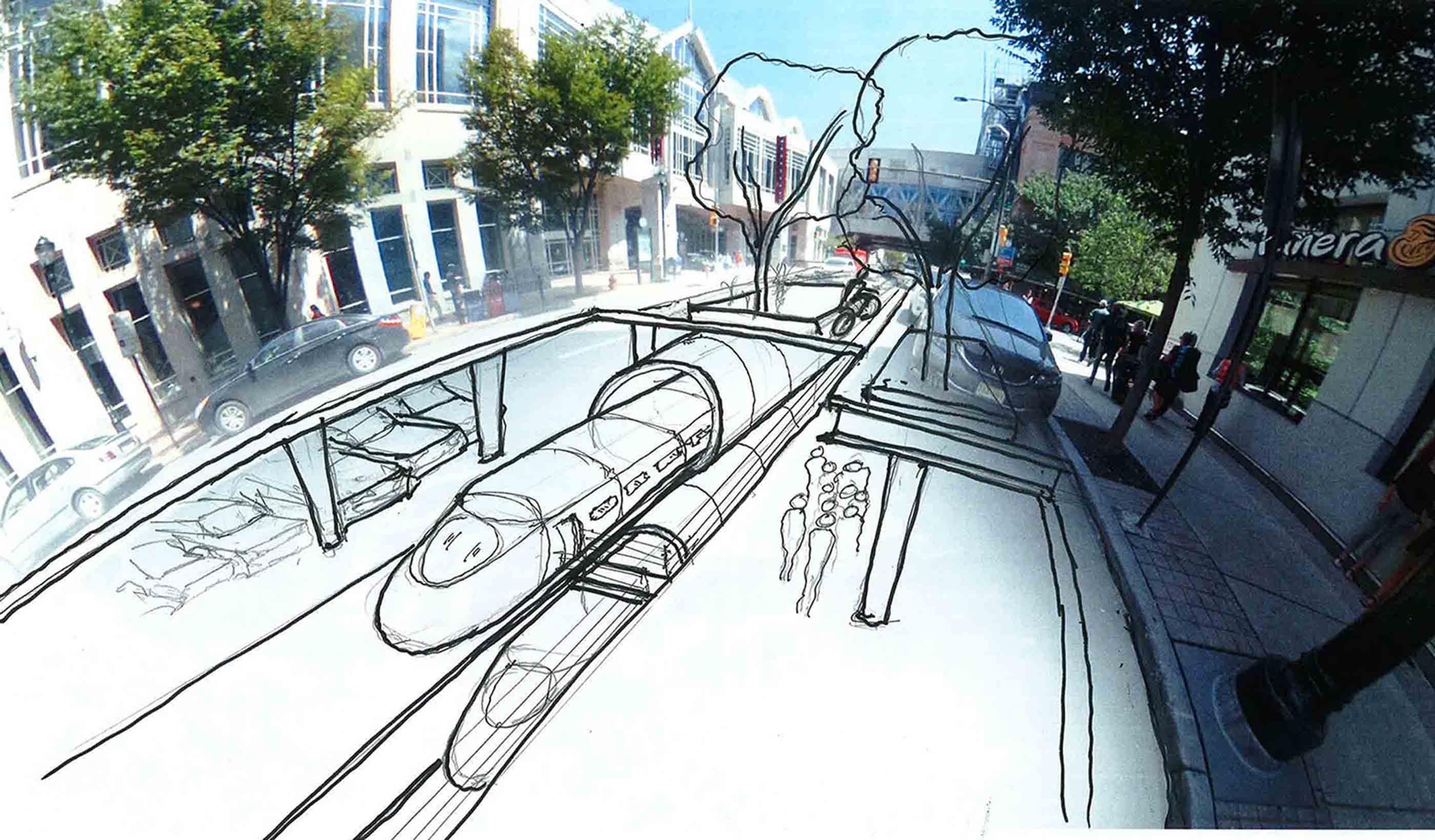

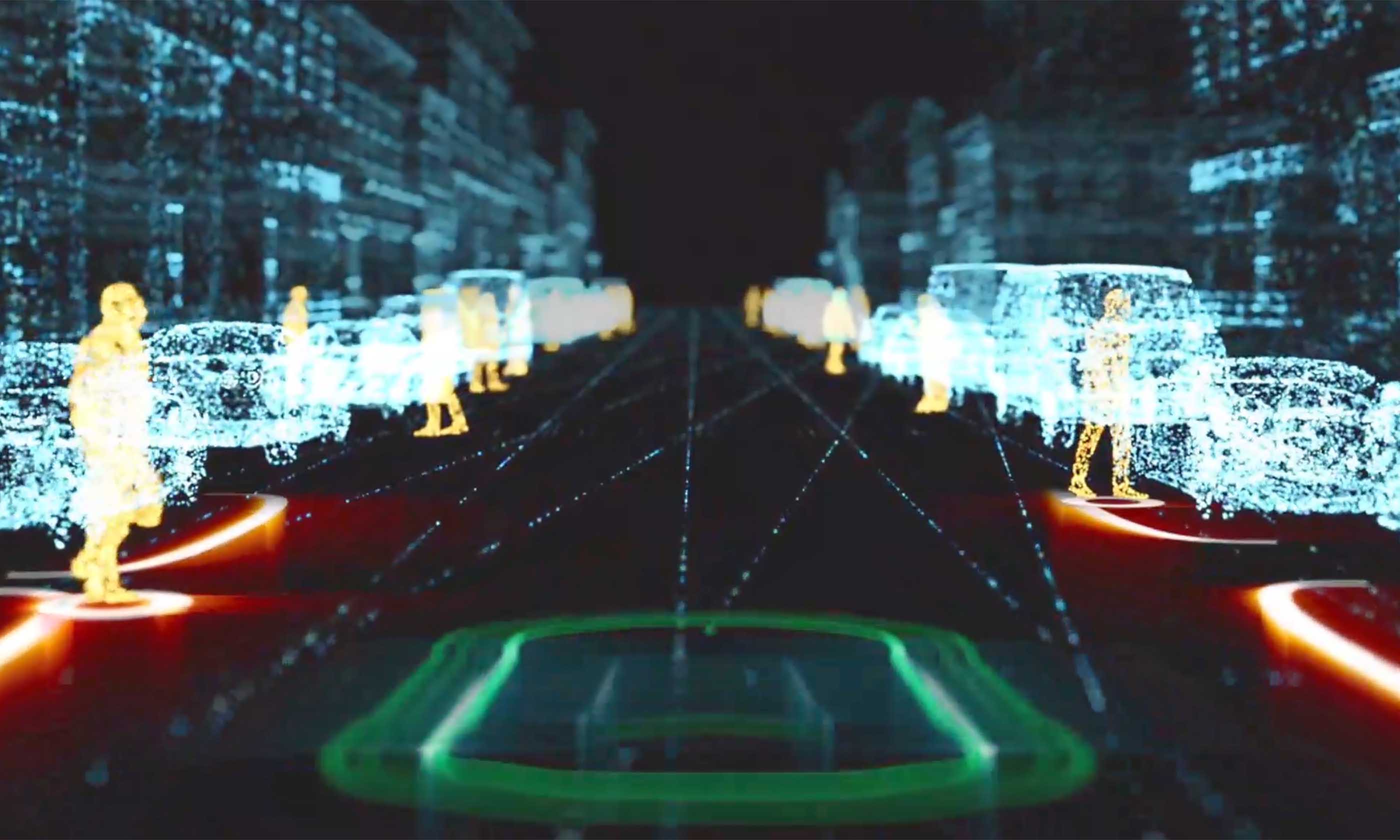

Video I’m an Innovator: Shaping policy discussions around the future of mobility

-

Blog Post Cleaner coasts: Turning the tide on trash capture

-

Blog Post How can water risk assessments build redundancy in your water supply?

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: Using innovation and technology to predict devastating debris flows

-

Podcast Asset Management Visionaries: Getting value out of your infrastructure

-

Blog Post Go slow to go fast: How to improve hosting and loading capacity maps for interconnection

-

Blog Post Affordable housing design: 10 ways to focus on engagement in residential projects

-

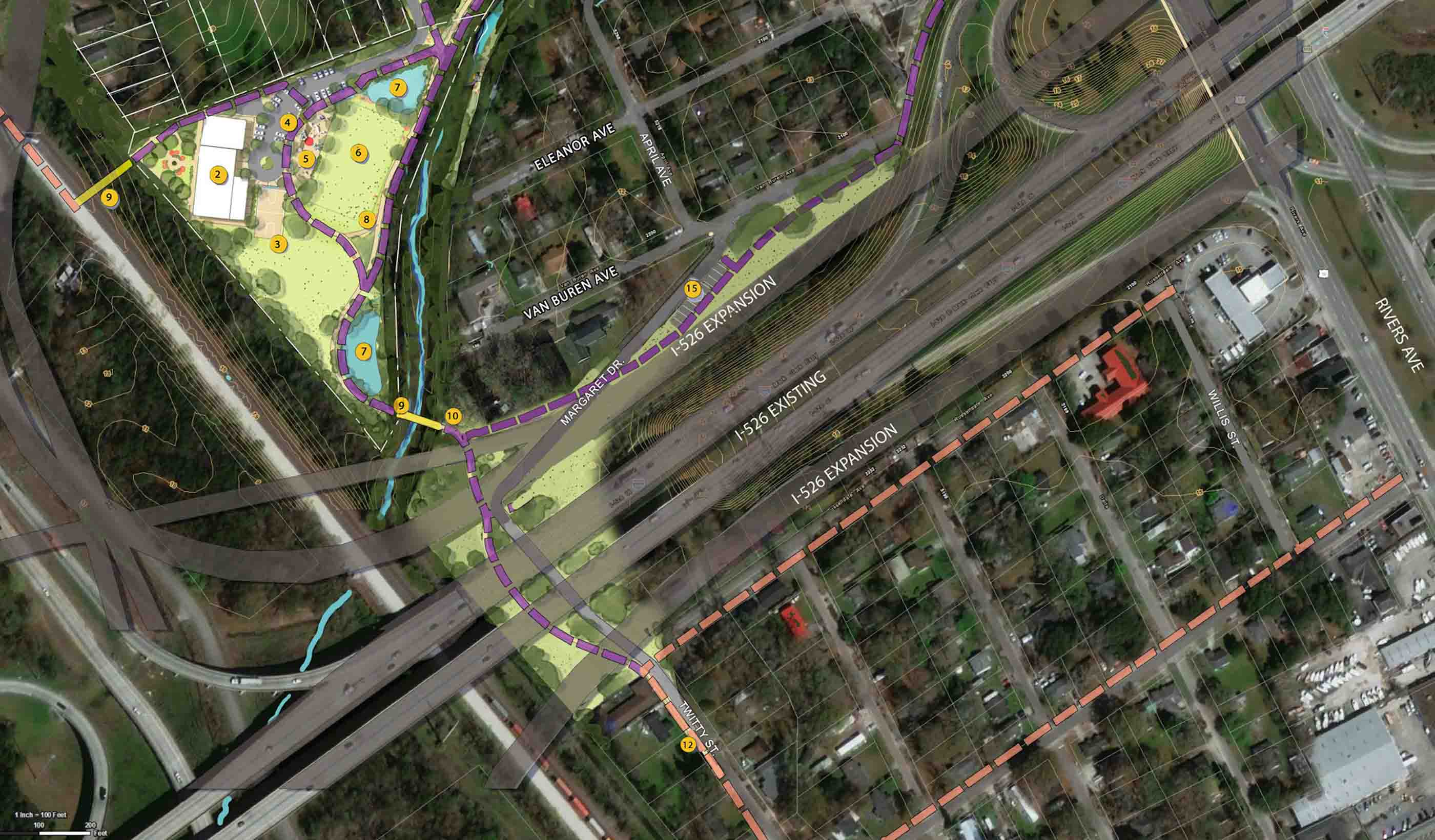

Webinar Recording Covering your highway: Here’s a how-to guide to reconnect your communities

-

Published Article Bridging the gap: Bringing agile innovation to the water sector

-

Published Article Anchorage airport infrastructure: Projects moving forward

-

Published Article The benefits of an UBI

-

Technical Paper Physically based dimensionless features for pluvial flood mapping with machine learning

-

Blog Post EV charging plans: What if every US vehicle were electric? Where do the charging sites go?

-

Blog Post Career-focused education: How industry partnerships help schools, students, and designers

-

Video Innovation in action: Empowering resilience through debris flow prediction

-

Published Article Environmental footprints: Tackling the impacts of historical mines

-

Blog Post How do we promote access to healthcare in Hawaii? Start with the Spirit of ʻOhana

-

Published Article Crafting calm from crisis

-

Report Direct vision transition guide: An operator’s guide to transforming fleets for safety

-

Published Article Progressive design-build delivers a high-risk, high-reward bioenergy facility

-

Blog Post What is a lifestyle hotel? Plus 6 questions about hospitality’s current direction

-

Webinar Recording Integrating approaches to maximize water resiliency—some call it One Water

-

Published Article Designing mine sites with less carbon-intensive energy infrastructure

-

Published Article Innovation, market incentives can drive electrification

-

Podcast Cyber threats in our water supply: What utilities need to know

-

Blog Post Q&A: Keeping up with design visualization—deploying new technology like AI in architecture

-

Blog Post A new underground substation: 9 things you need to know

-

Published Article A boring new technique for sewer repair comes to the South Side

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: How do innovative minds approach complex problem solving?

-

Podcast Design Hive: Greg Hall on advanced manufacturing and how to design for it

-

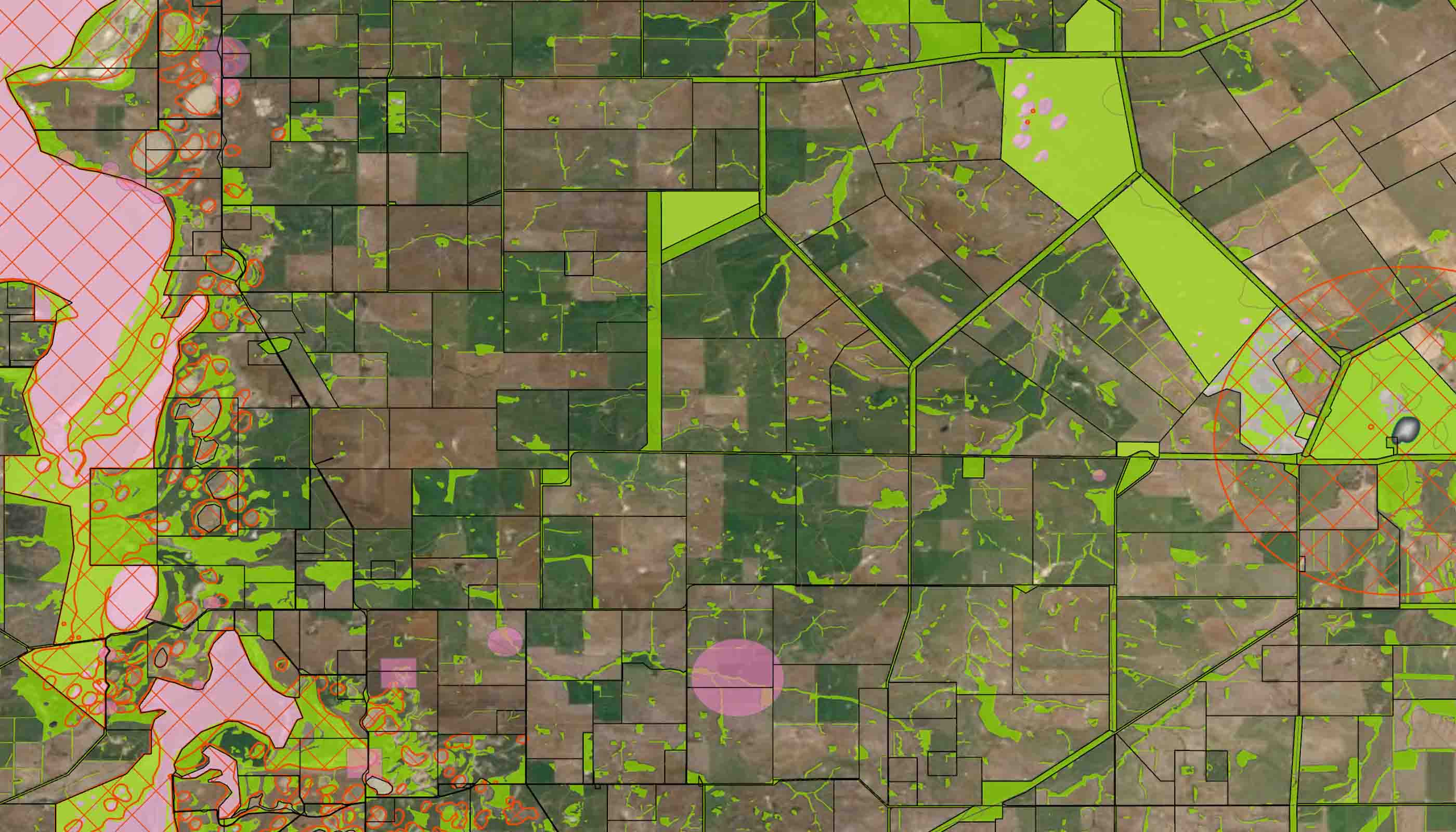

Blog Post Unlocking efficiency: GIS tools modernize utility management

-

Publication Design Quarterly Issue 24 | Engage

-

Published Article Achieving the best in mine ventilation

-

Video Managing your nature-related risks and opportunities for enhanced long-term sustainability

-

Blog Post Cybersecurity defense in the water industry: 3 steps utilities can take now

-

Video Innovation Insights: How to launch novel ideas in mining technology

-

Blog Post America’s water infrastructure needs help: Here are 3 ways to strengthen it

-

Video How can we reduce carbon use and boost sustainability at airports?

-

Webinar Stantec Water Webinar Series—2025 presentation schedule

-

Blog Post How can communities efficiently fund flood-mitigation efforts?

-

Blog Post Reducing carbon emissions for hard-to-electrify industries

-

Blog Post Electrifying our grids: The role of HVDC technology

-

Blog Post Renewable energy and electrification rely on critical minerals and metals

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: Can workplace robotics help create high-performance workspaces?

-

Blog Post The demand for energy and water at data centers

-

Blog Post Electrification: A key driver for a greener tomorrow

-

Blog Post Designing the infrastructure to electrify our transportation industry

-

Published Article Collaboration makes rare mile-long stream restoration opportunity a reality

-

Blog Post Sustainable data centers: 3 ways to get there

-

Podcast CAV innovation in Louisiana: Previewing a first-of-its-kind event

-

Video Removing barriers with airport design

-

Webinar Recording Roundtable: 5 ways to spark innovation that leads to impact

-

Blog Post Is a mix of housing missing from your mall redevelopment equation?

-

Published Article How water reuse projects are addressing water scarcity in the West—and beyond

-

Published Article Sustainable and resilient airport design

-

Blog Post Hydrogen’s thirst: How much water supply is required for sustainable energy?

-

Published Article Cement manufacturers should adopt a holistic approach

-

Video Innovation Insights: Building new business through innovation

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The impact of nature-based solutions in design and engineering

-

Published Article LED luminaires are reaching end of life—now what?

-

Blog Post The benefits of health data portability—and how to design for it

-

Podcast Design Hive: Tariq Amlani on healthcare decarbonization

-

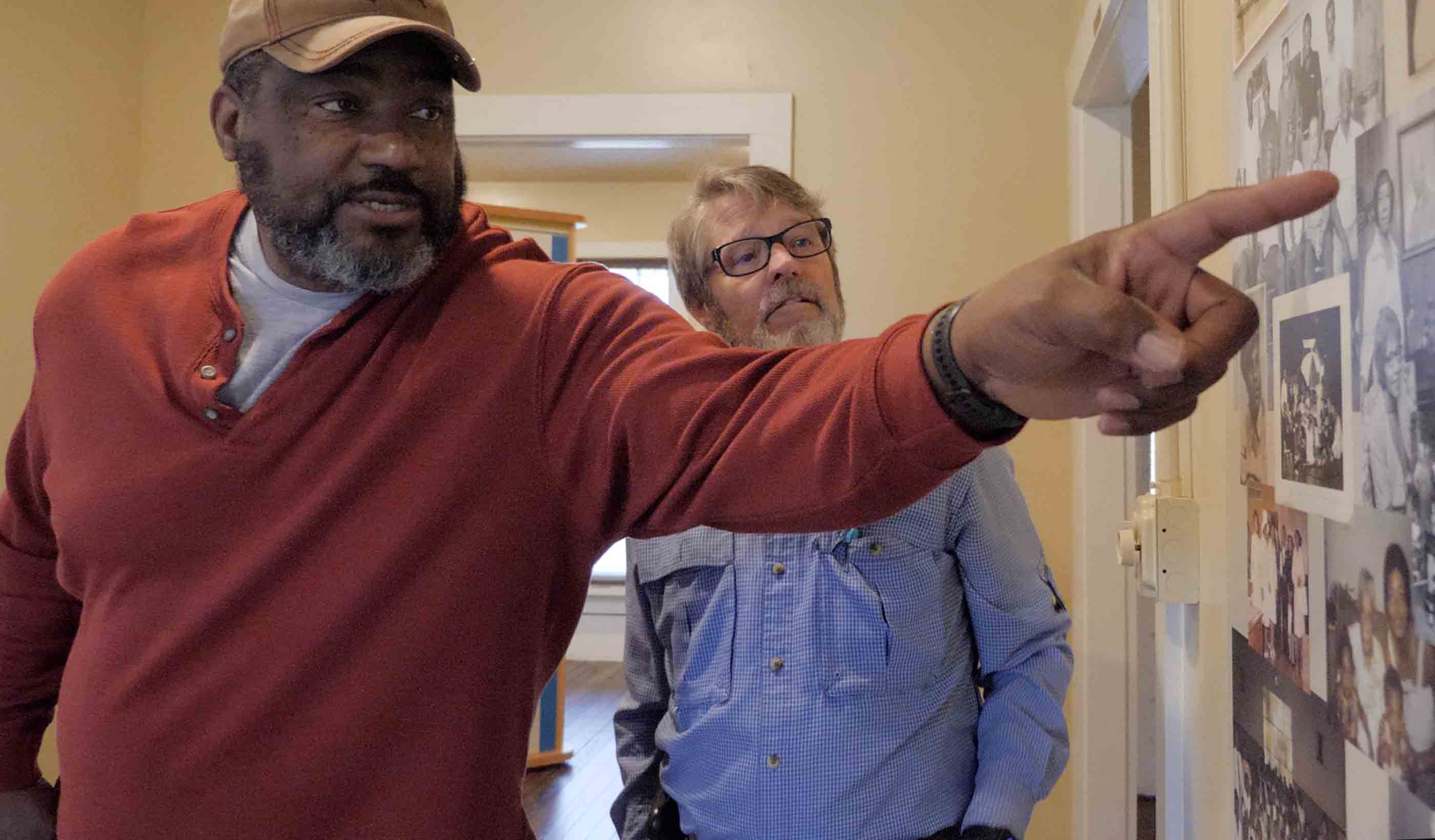

Published Article Cultural restoration: Community visions collaborate to reclaim cherished landscape

-

Video Manhattan’s waterfront: Building relationships to redefine what’s possible

-

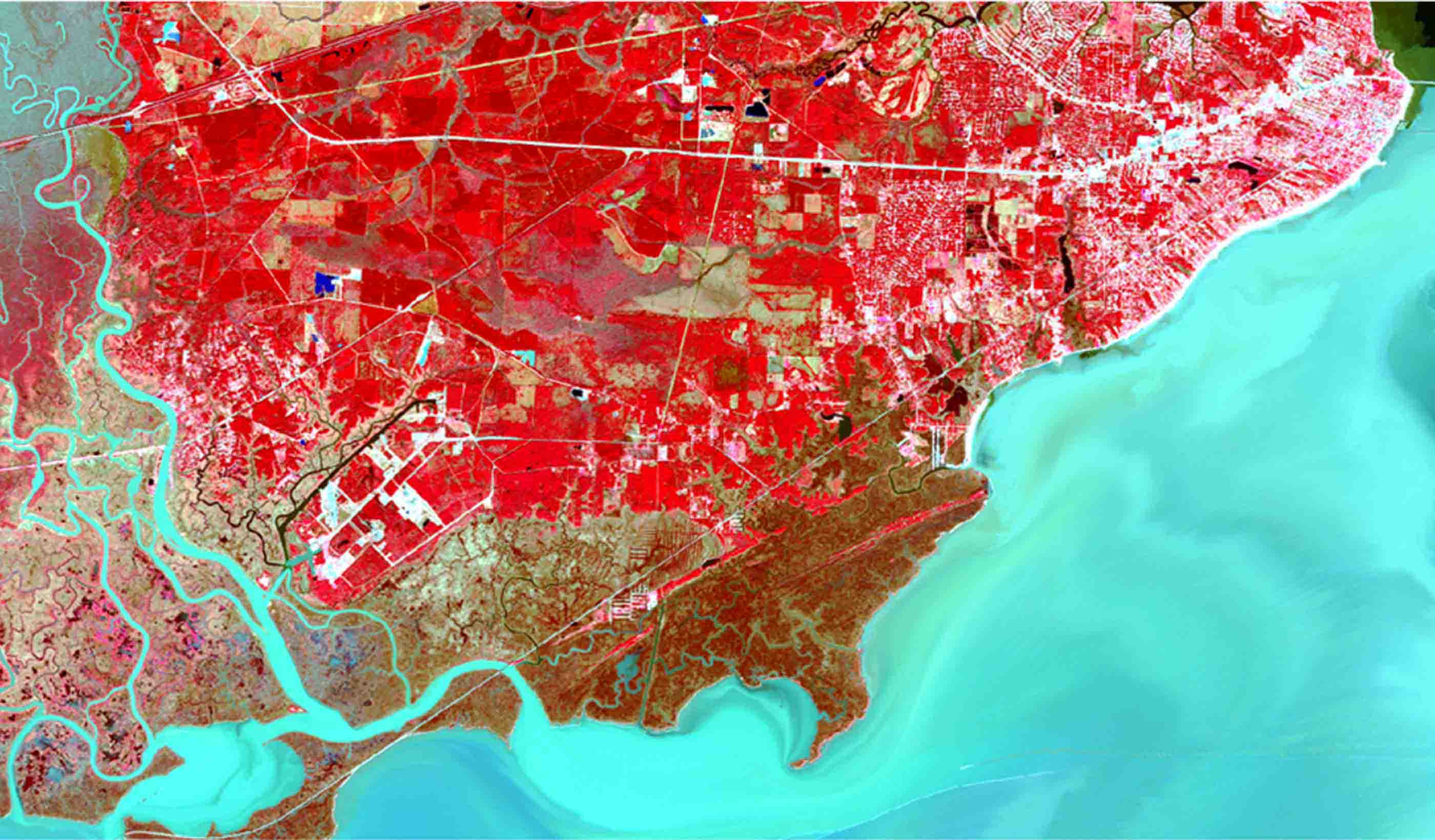

Published Article Remote sensing, 3D mapping help find answers in Tulsa

-

Video Building a sustainability framework: A path to managing risks and increasing value

-

Blog Post Unlocking safety: 7 steps to designing hazardous manufacturing facilities

-

Video Innovative airport design taking flight

-

Video Construction management to deliver the first driverless light rail system in the US

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: How pumped storage hydropower can help the global energy transition

-

Published Article Long-term care of the planet

-

Published Article An energy conservation mindset

-

Blog Post Who needs a helium-recovery system?

-

Blog Post How can water utilities transition to a One Water approach? 5 practical steps

-

Video Innovation Insights: Carbon capture innovation in the fight against climate change

-

Blog Post Sustainability in higher education (Part 1): Start with a carbon neutral master plan

-

Blog Post Optimizing the design of data center utilities

-

Blog Post 3 strategies for building modern irrigation to help feed the world

-

Video What are the flood-mitigation challenges for different-sized communities?

-

Published Article Understanding natural capital and how it informs ecosystem restoration

-

Published Article Finding low-impact development solutions in Edmonton

-

Blog Post Stantec’s Top 10 Ideas from 2024—plus 1 more for fun

-

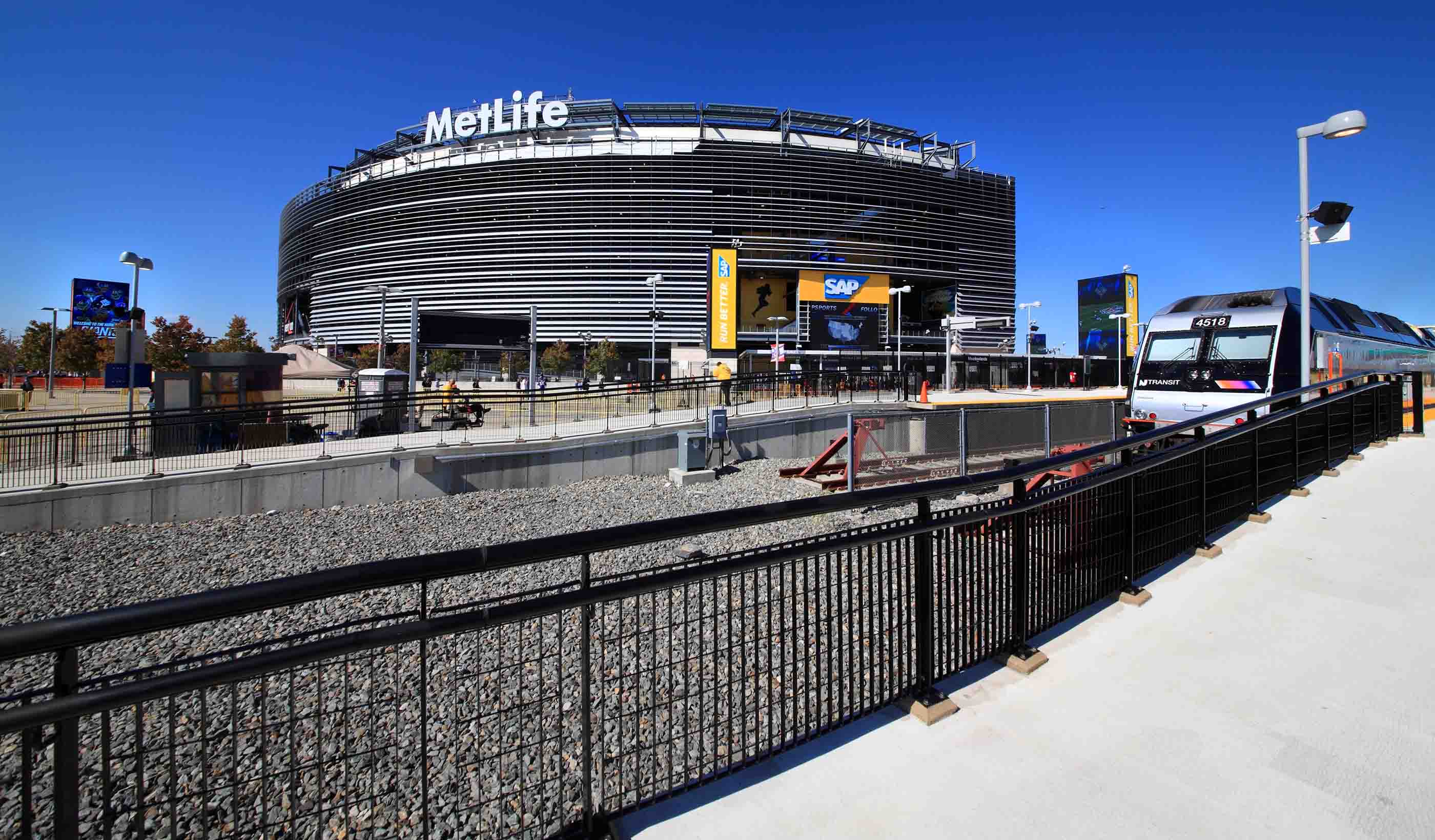

Blog Post Beyond the game: Sports stadium design for world-class events

-

Publication Design Quarterly Issue 23 | Technology update

-

Published Article Tear it down or start it back up? Plant owners weigh options around retired reactors

-

Webinar Recording The evolving role of machine learning and artificial intelligence technologies in water

-

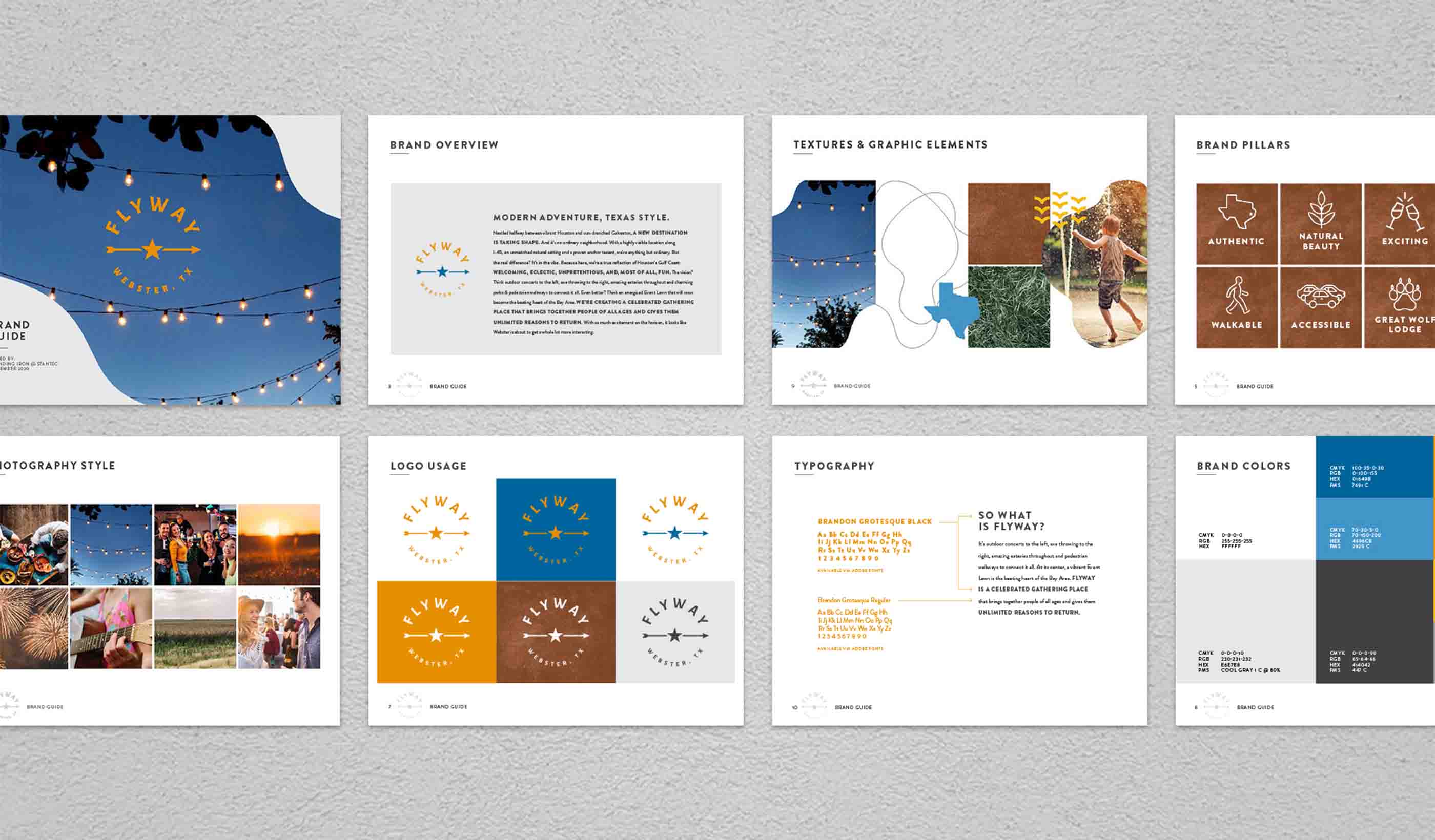

Blog Post Storytelling for buildings: Why real estate branding matters

-

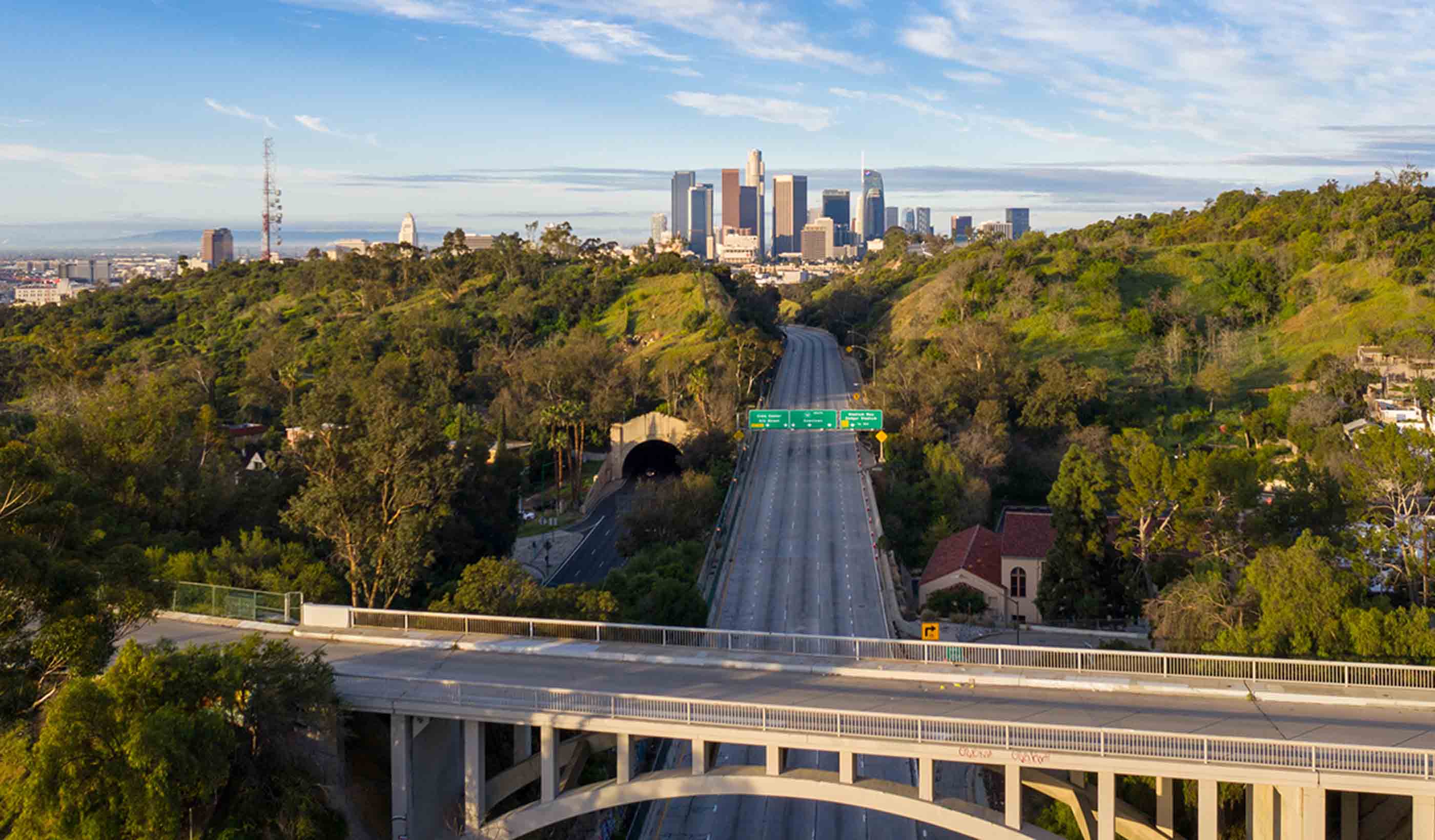

Blog Post Rethinking resilient infrastructure for transit in the face of climate change

-

Video Innovation Insights: How important is communication and client dialogue?

-

Blog Post Bridging innovative water solutions and practical needs for water infrastructure upgrades

-

The impossible fix: Engineering under London

-

Blog Post Overcoming challenges in wind turbine transportation: Why route assessments are critical

-

Video The energy transition is about more than just renewables

-

Video A billion decisions: Engineering better projects

-

Video I’m an Innovator: Helping communities transition to electric vehicles more efficiently

-

Blog Post Breaking up with the mega hospital: Redefining healthcare campus master planning in Canada

-

Webinar Recording PFAS source water assessments, waste treatment, and operational factors for the new MCLs

-

Blog Post 7 elements of successful cultural center design

-

Published Article Consulting on complexities

-

Webinar Recording Small modular reactors: A renaissance for nuclear power

-

Published Article The impact of AI and cameras on physical security design

-

Published Article Restorative work

-

Blog Post Protecting solar farms from the elements: Geohazard mitigation for large-scale solar farms

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: Digital innovation in buildings

-

Blog Post Recalculating ROI for a commercial building retrofit

-

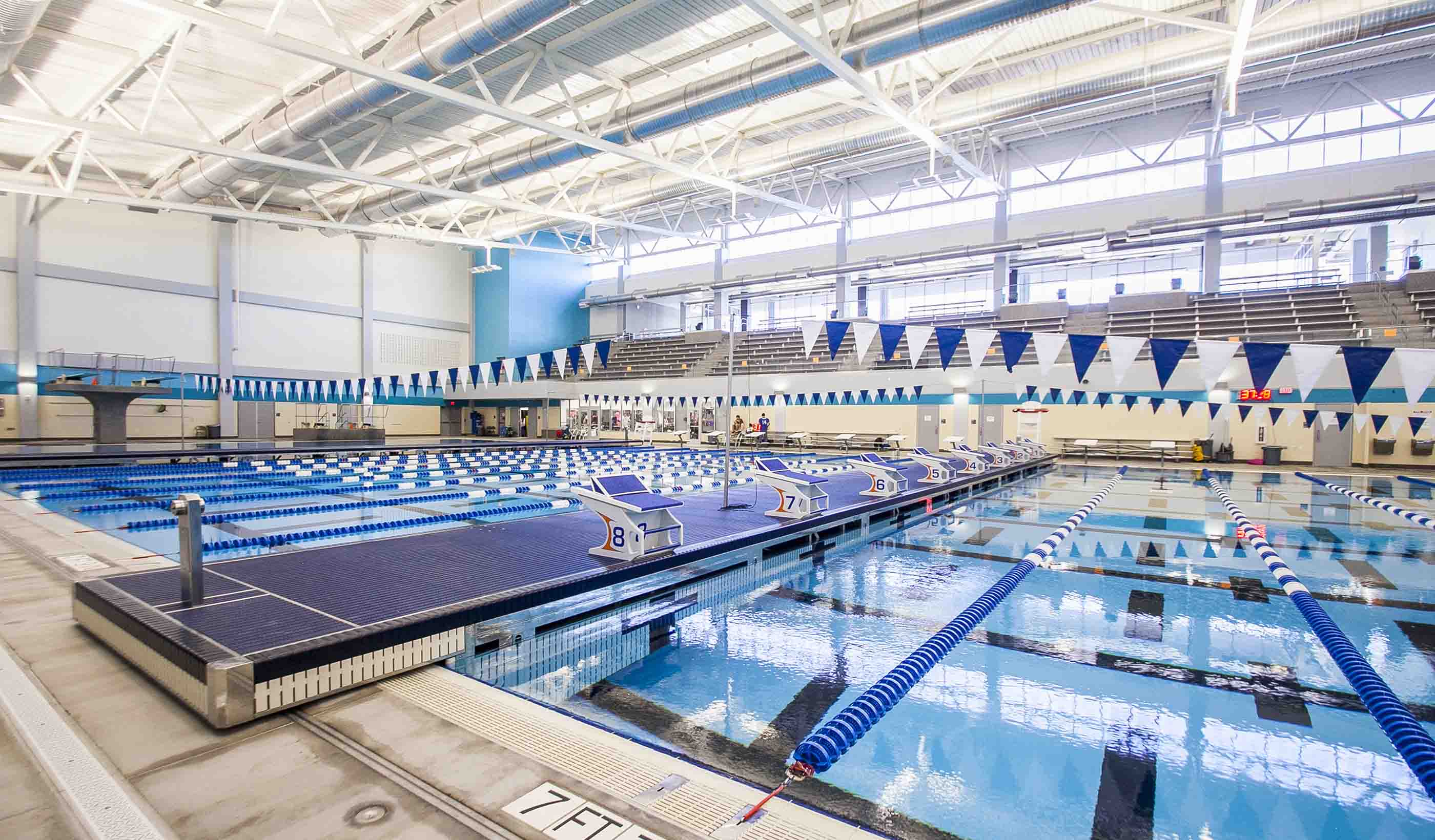

Published Article Raising the bar for athletic facilities

-

Published Article Water consumption concerns as data center use increases

-

Video Stantec and BBC StoryWorks: AI-driven flood modeling and its impact on flood prediction

-

Blog Post Developing sustainable mine-closure plans for legacy tailings-storage facility management

-

Technical Paper The sedimentology of high perm streaks and reservoir heterogeneity: Implications for CCS

-

Published Article Pay dirt: Stantec digs for opportunity in the race against climate change

-

Video Innovation Insights: Exercising discipline in the world of hydrogen energy

-

Blog Post Fueling the future: The promise of hydrogen fuel

-

Webinar Recording Innovative treatment technologies: Balancing nutrient removal and energy management

-

Blog Post PPER (Part 2): How to prepare for Canada’s updated Pulp and Paper Effluent Regulations

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: Developing digital solutions

-

Published Article Edmonton's Stantec set to refine power grids in BC and US

-

Webinar Recording Placemaking for innovation: Creating innovation ecosystems

-

Published Article Microsoft would restart Three Mile Island Nuclear Plant to power AI

-

Video Mining critical minerals for the energy transition

-

Published Article How to build awareness of flood risk and gain buy-in for flood control measures

-

Webinar Recording Getting the most out of your water storage tank

-

Blog Post PPER (Part 1): What do Canada’s updated Pulp and Paper Effluent Regulations mean for you?

-

Video 6 schools in 3 years through unique delivery

-

![[With Video] Delivering equity through P3 school design](/content/dam/stantec/images/projects/0134/prince-george-county-schools-walker-mill-228421.jpg)

Blog Post [With Video] Delivering equity through P3 school design

-

White Paper How high-quality carbon credits achieve climate action goals and avoid greenwashing

-

Coastal power plant anti-corrosion practices

-

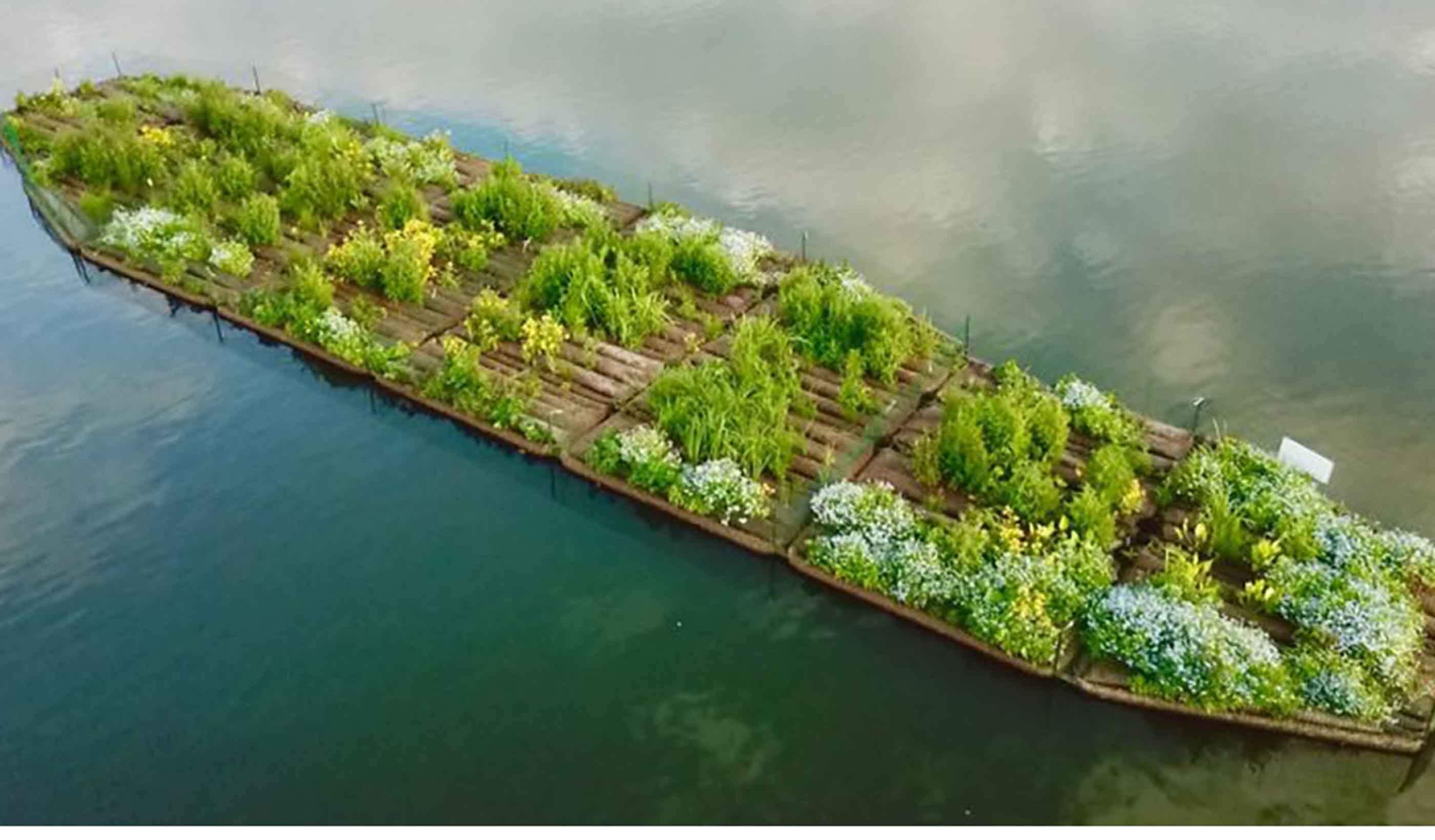

Published Article Understanding nature-based solutions: How NbS can address many environmental challenges

-

![[With Video] Can multisensory spaces help reduce anxiety, stress in university students?](/content/dam/stantec/images/projects/0134/macewan-university-240745.jpg)

Blog Post [With Video] Can multisensory spaces help reduce anxiety, stress in university students?

-

Published Article Long-awaited SunZia to transmit wind power

-

Blog Post Understanding the hidden world of submarine telecommunication cables

-

Video Innovation Insights: The importance of company culture

-

Published Article In a changing world, better flood modeling informs designs that stand up

-

Published Article Using chilled beams for lab ventilation to maximize energy efficiency

-

Blog Post Water storage tanks 101: Getting the most out of your tank

-

Blog Post Breaking down data silos in infrastructure asset management

-

Webinar Recording Designing, building, and operating: Connecting the full cycle of asset lifecycle

-

Published Article Mine reclamation planning: Q & A

-

Blog Post Office building asset repositioning: What should you look for?

-

Published Article Rising to meet a critical future

-

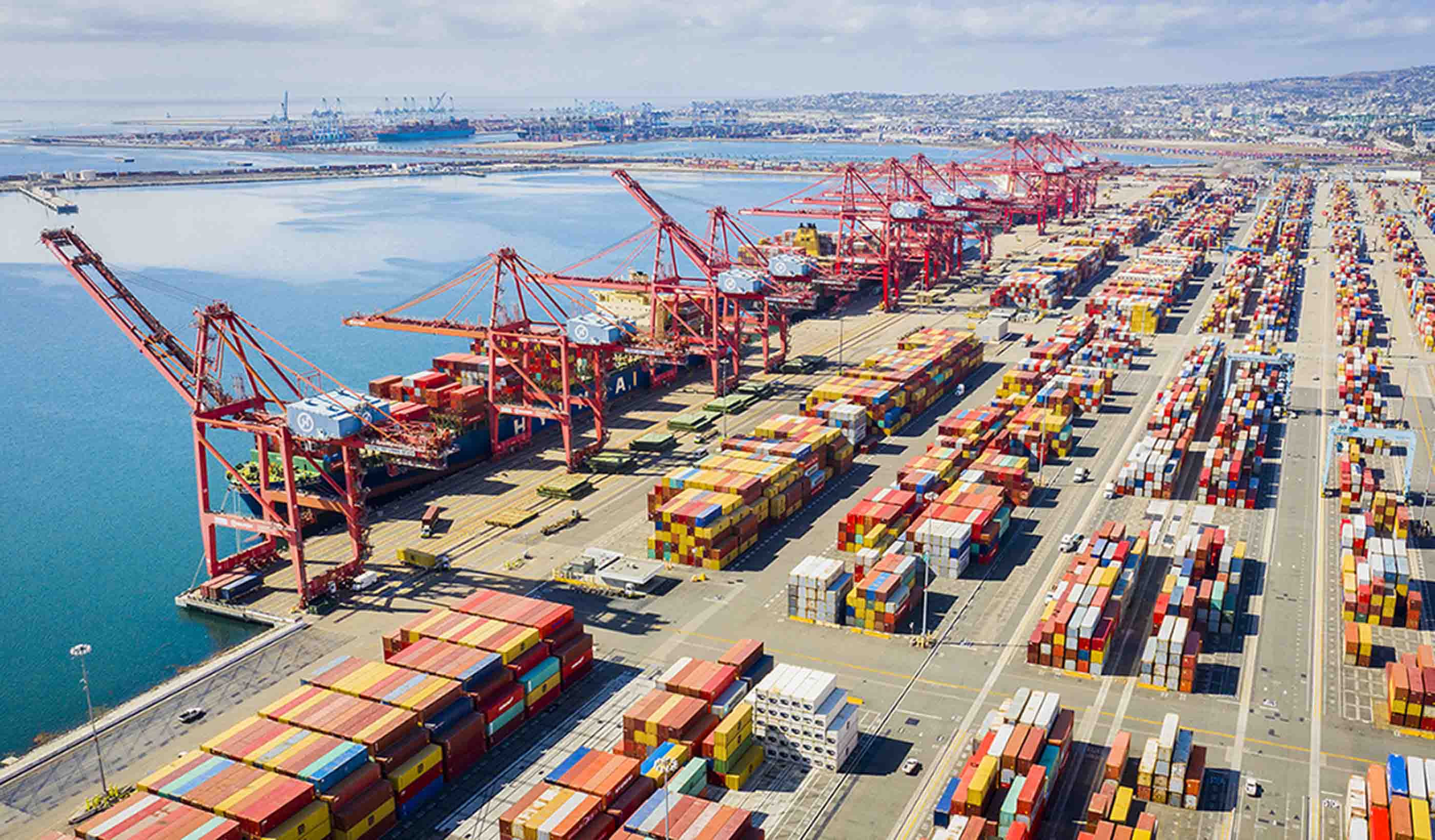

Blog Post Do we have the port infrastructure to support offshore wind development?

-

Blog Post Navigating water security with increasing food demand

-

Video Innovation Insights: Small modular reactors and trusting the process

-

Blog Post 3 reasons for adaptive building reuse

-

Publication Design Quarterly Issue 22 | Experiences

-

Podcast Design Hive: Jan Wei on NYC’s Local Law 97 emission limits

-

Blog Post 4 considerations for your next grid-modernization project

-

Blog Post The water industry is turning to progressive design-build. Here’s why.

-

Published Article How to design resilient power systems in data centers

-

Blog Post Connecting the Canadian Arctic through infrastructure and Indigenous knowledge

-

Video Designing Canada’s largest solar farm

-

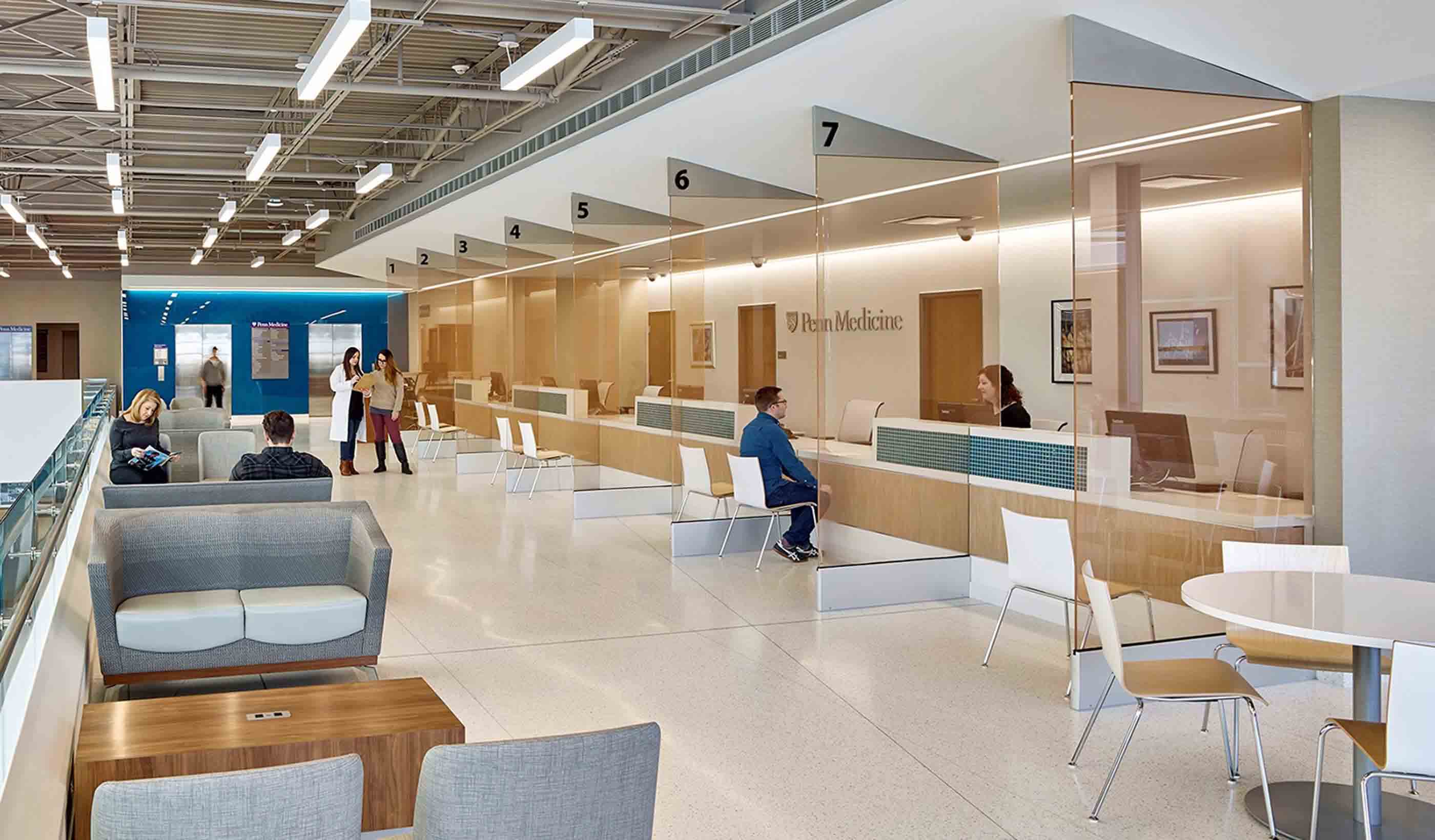

Blog Post Collaborative care: Boundaryless healthcare design for outpatient clinics

-

Published Article Hydropower remains renewable leader despite climate challenges

-

Blog Post Reducing shark depredation to support Cocos Islands economy and Australian marine ecology

-

Video Innovation Insights: How does market research impact innovation?

-

Published Article US Government helps nuclear energy allies catch up to Russia, China

-

Blog Post 6 big net zero design ideas for a Houston Astrodome renovation

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The Artificial Intelligence Episode

-

Video With every community, Stantec redefines what’s possible

-

Blog Post Do you account for your land GHG emissions? The GHG Protocol has new guidance for you

-

Blog Post With new CSA standards, healthcare systems will need a decarbonization roadmap

-

Blog Post Why progressive design-build is gaining traction in Canada

-

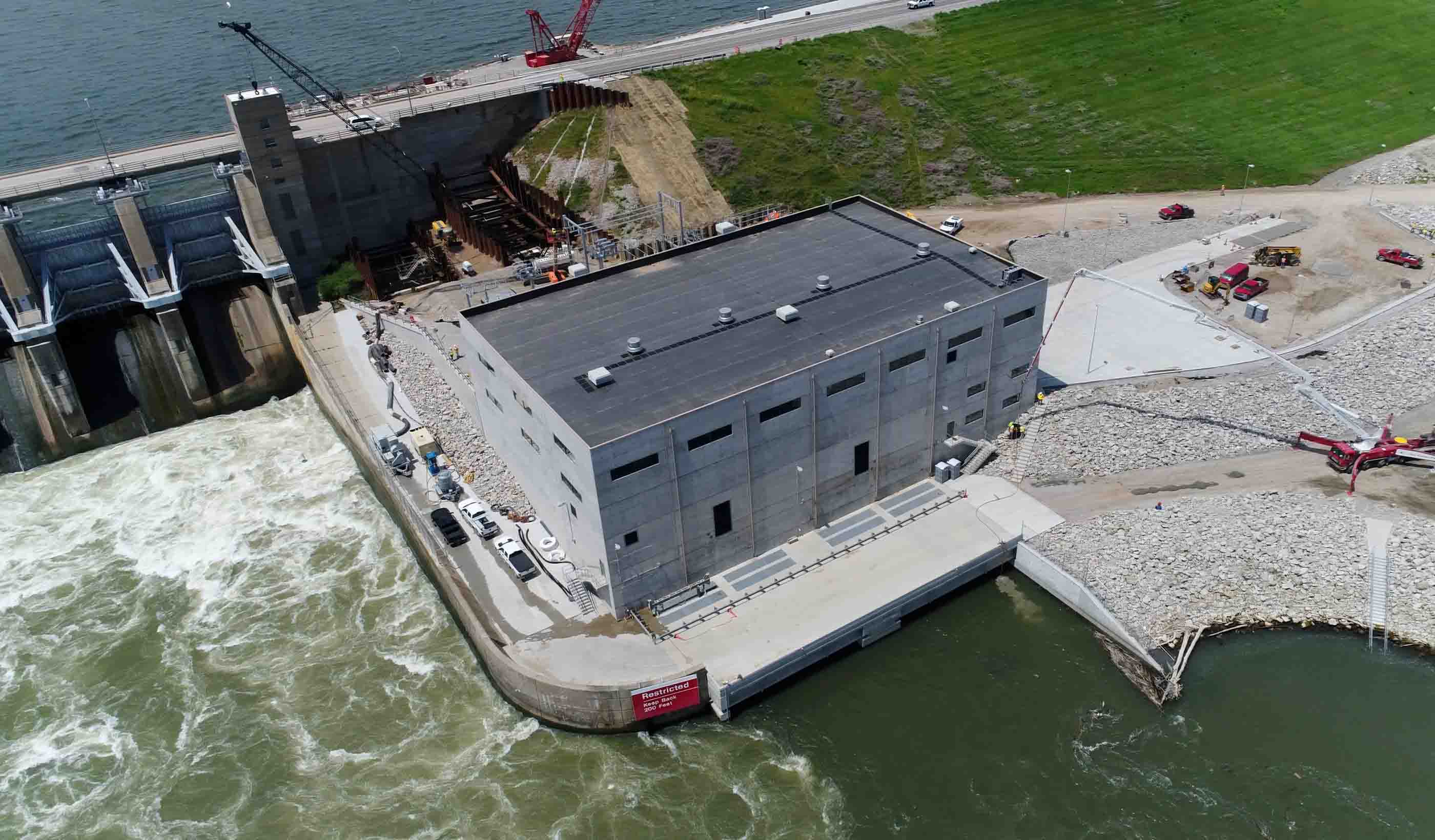

Published Article Seismic resilience boost: Priest Rapids Dam undergoes major upgrades

-

Published Article In tune with nature: Nature-based mine reclamation

-

Blog Post Retrofitting existing infrastructure to get the most value from our resources

-

Blog Post Redefining water reuse to combat the global water crisis

-

Reinventing mine closure: Creating assets for the future

-

Blog Post Repurposing pipelines for the energy transition

-

Blog Post Rethinking energy storage: Looking beyond batteries

-

Blog Post A new life for waste: Advancing a circular economy

-

Published Article From scar to a community resource—Pikeview Quarry’s reclamation journey

-

Video I'm an Innovator: Automating the design of solar facilities

-

Blog Post Aligning ESG in commercial real estate

-

Webinar Recording Navigating the EPA’s revisions to the Steam Electric Effluent Limitations Guidelines

-

Blog Post California climate disclosures: 5 things you can do now to get ready for the new rules

-

Published Article Getting the green light: Permitting mines in the US Southwest

-

Blog Post Smart utility readiness: Are you prepared to become a digital water or wastewater utility?

-

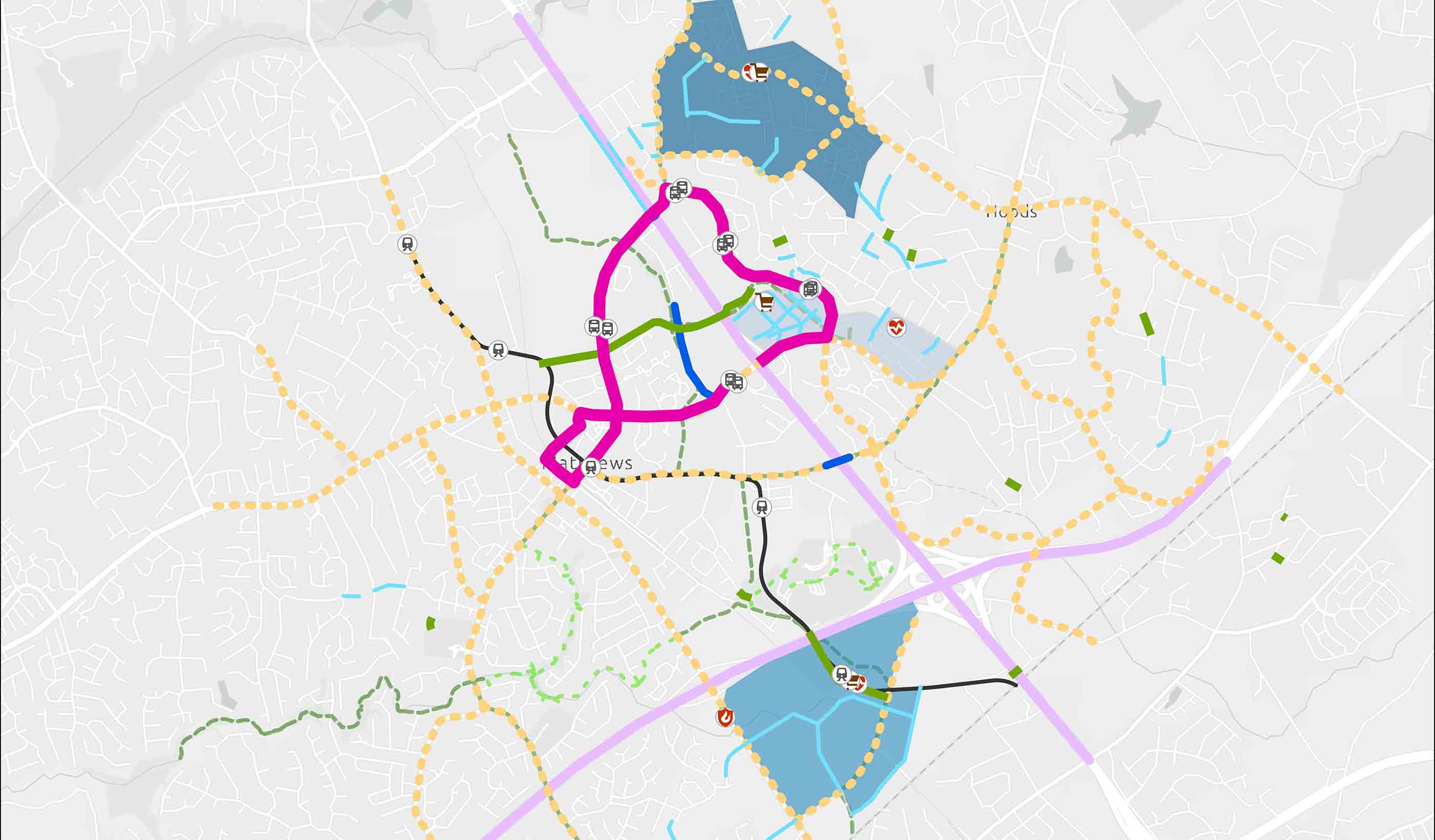

Case Study A data-driven approach to transit planning and equity

-

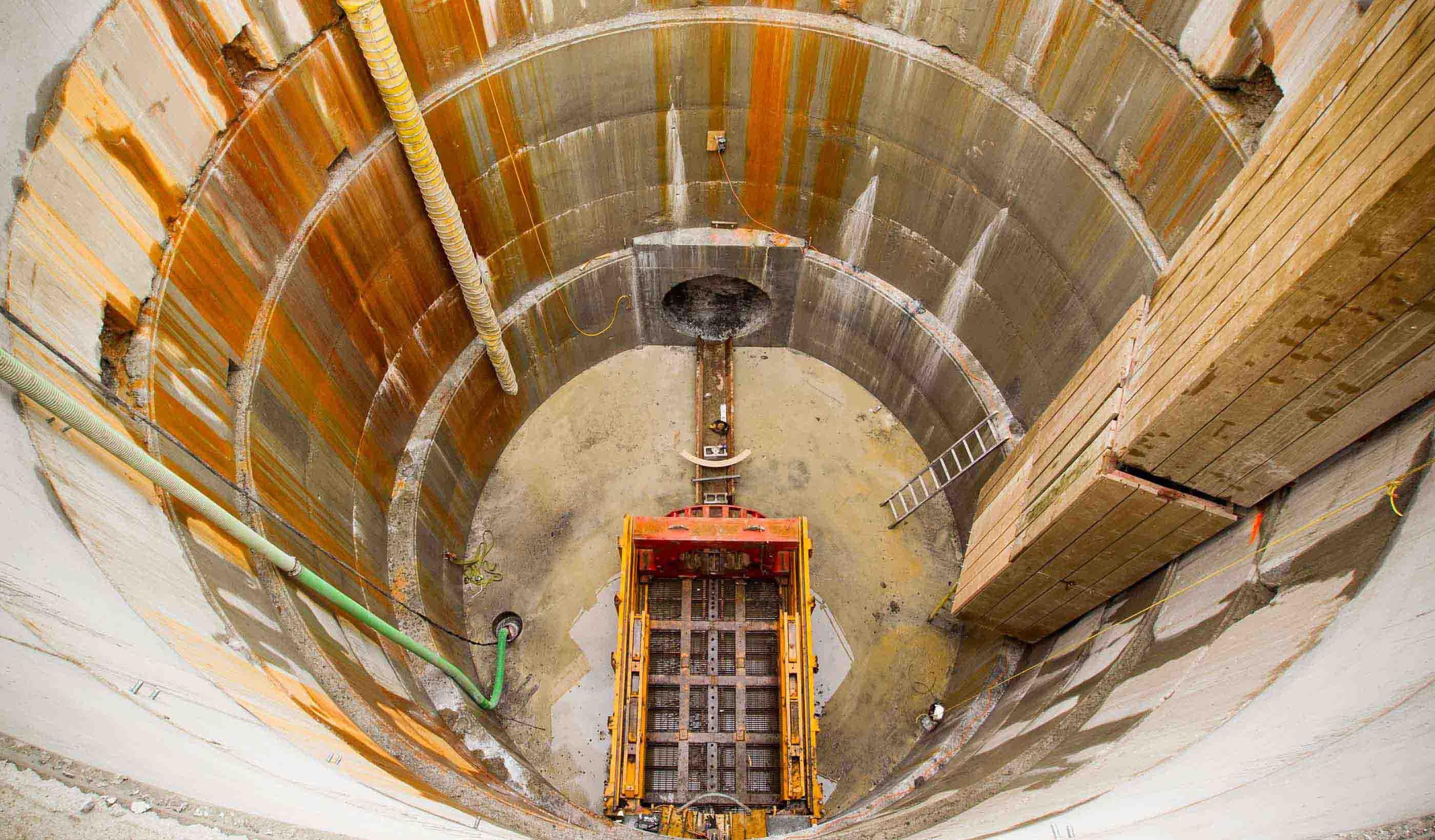

Published Article Markham, Ontario incorporates microtunneling in its York Downs Sanitary Sewer Connection

-

Video Nature-based solutions: Using engineering and nature to solve environmental challenges

-

Published Article Emergency renewal: Renew Sinai—Phase 3A emergency department renovation

-

Published Article AI meets analogue: Harmonizing mock-ups with generative AI

-

Report Enhancing Montreal’s public spaces through strategic urban design

-

Blog Post Scaling up your critical minerals processing with demonstration plants

-

Published Article Stantec confirms that environmental services have a key role to play in hydrogen projects

-

Podcast Design Hive: Beth Tomlinson on building decarbonization and ASHRAE standards

-

Published Article Stantec reflects on state of play in hydrogen infrastructure, production, and transportation

-

Blog Post SEC climate disclosure rules: 4 strategies to kick start your climate-risk management plan

-

Webinar Recording Focused investigation is good, but focused rehab is better! Strategies for managing I/I

-

Blog Post Time to invest in water automation? How to tackle 5 operational technology challenges

-

Published Article Project delivery, modernization, and more with Dena Abakumov

-

Published Article 3 trends guiding architectural design trends for autism providers

-

Blog Post How can design respond to burnout in healthcare professionals?

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The Decarbonization Episode

-

Published Article Decentralized renewables fuel sustainability

-

Blog Post Planning for PFAS: How can we approach biosolids management amid changing regulations?

-

Published Article Filtering through: Trends in tailings management

-

Blog Post Large-scale redevelopment projects need to learn from small-scale historic neighborhoods

-

Publication Research + Benchmarking Issue 04 | Inclusion, Diversity, and Wellness

-

Blog Post Net zero building design starts with industry climate pledges

-

Published Article How virtual reality could transform architecture

-

Podcast The Construction Record Podcast™–Episode 342–Stantec’s Jag Singh on small modular reactors

-

Published Article Biden CO2, hydrogen pipeline dreams get wake-up call

-

Video Designing sustainability into Edmonton's LRT expansion

-

Published Article Four considerations for large pump station design

-

Blog Post Low-carbon energy solutions for mine sites

-

Blog Post Preparing for building performance standards in cities

-

Published Article Navigating volatile market conditions

-

Video How we decarbonize the mining industry

-

Blog Post How integrated thinking can help boost the energy transition

-

Technical Paper At the intersections of history

-

Publication Design Quarterly Issue 21 | Adaptive Reuse

-

Video Early childhood education in the modern world

-

Video A road project uncovered a historical archaeology site and one family’s connection to it

-

Podcast Steve Flinn talks about controllers and their nuances

-

Blog Post Transportation planning strategies for the FIFA World Cup and major events

-

Blog Post A single electricity market can increase affordability and reliability in Africa

-

Blog Post 6 tips for designing allied health education facilities

-

Webinar Recording Navigating the storm: Solutions for automation and innovations in operational technology

-

Blog Post Edge data centers can speed your online experience

-

Blog Post Driving decarbonization with renewable floating offshore wind energy

-

Webinar Recording No H2 without H2O

-

Video Interest is growing for recovering resources from wastewater

-

Video Prioritizing environmental justice on a $3 billion transportation megaproject

-

Published Article Mine by design

-

Blog Post Canada PFAS in the mining industry: Potential impacts, risks, and challenges

-

Blog Post A sustainable approach to readying critical minerals for decarbonization

-

Blog Post Designing a workplace experience to answer: ‘Why should I go into the office?’

-

Video How Albany converted an underused highway ramp into a city park

-

Blog Post Can we recycle captured carbon to produce green hydrogen and biomass?

-

Video I'm an Innovator: Using AI to classify loud noises at construction sites

-

Published Article 3 things to consider when creating a lead service line inventory

-

Published Article Live, work, play: Office building conversion practices for downtown revitalization

-

Blog Post Small modular reactors: Driving energy security with nuclear power

-

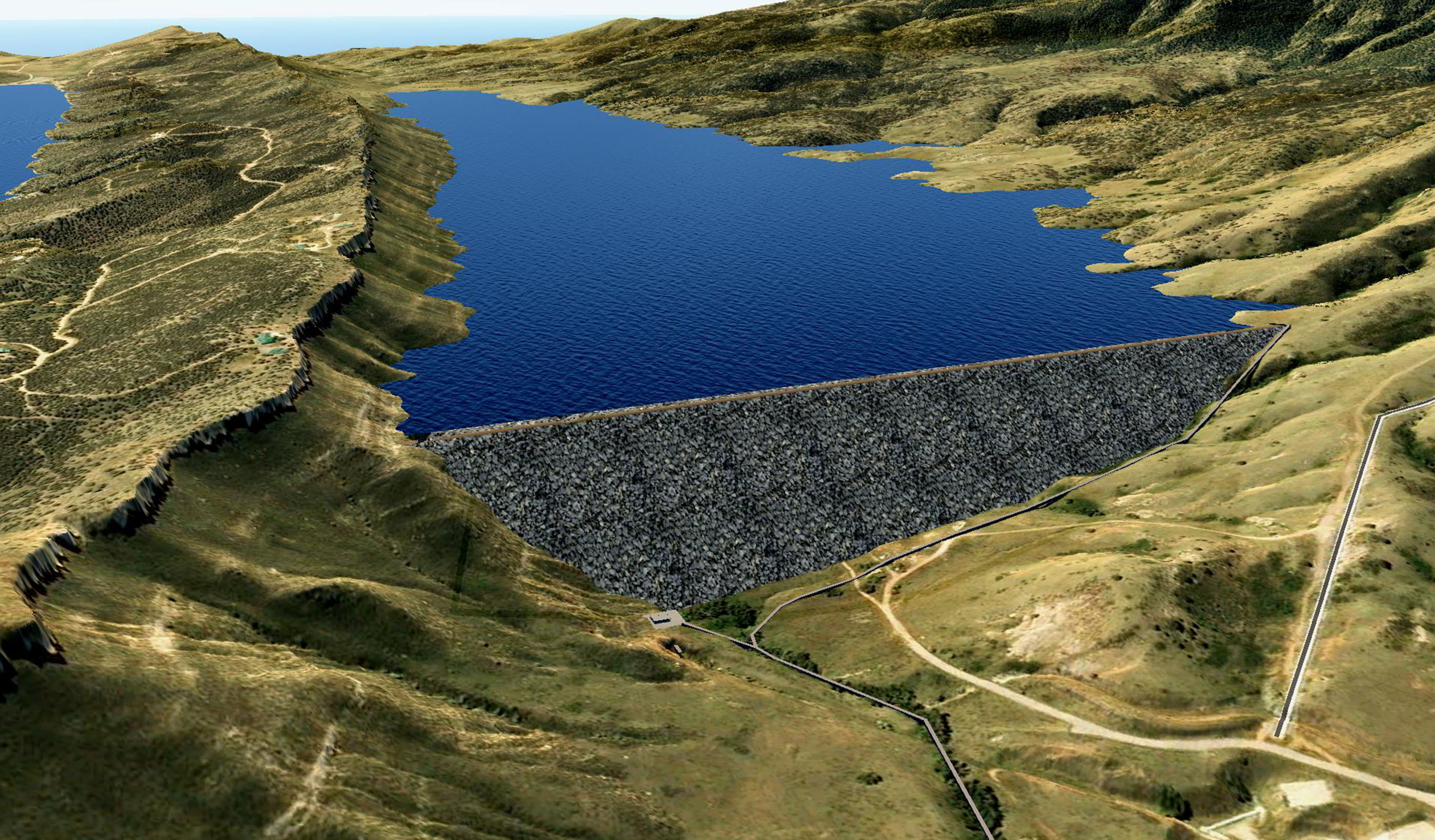

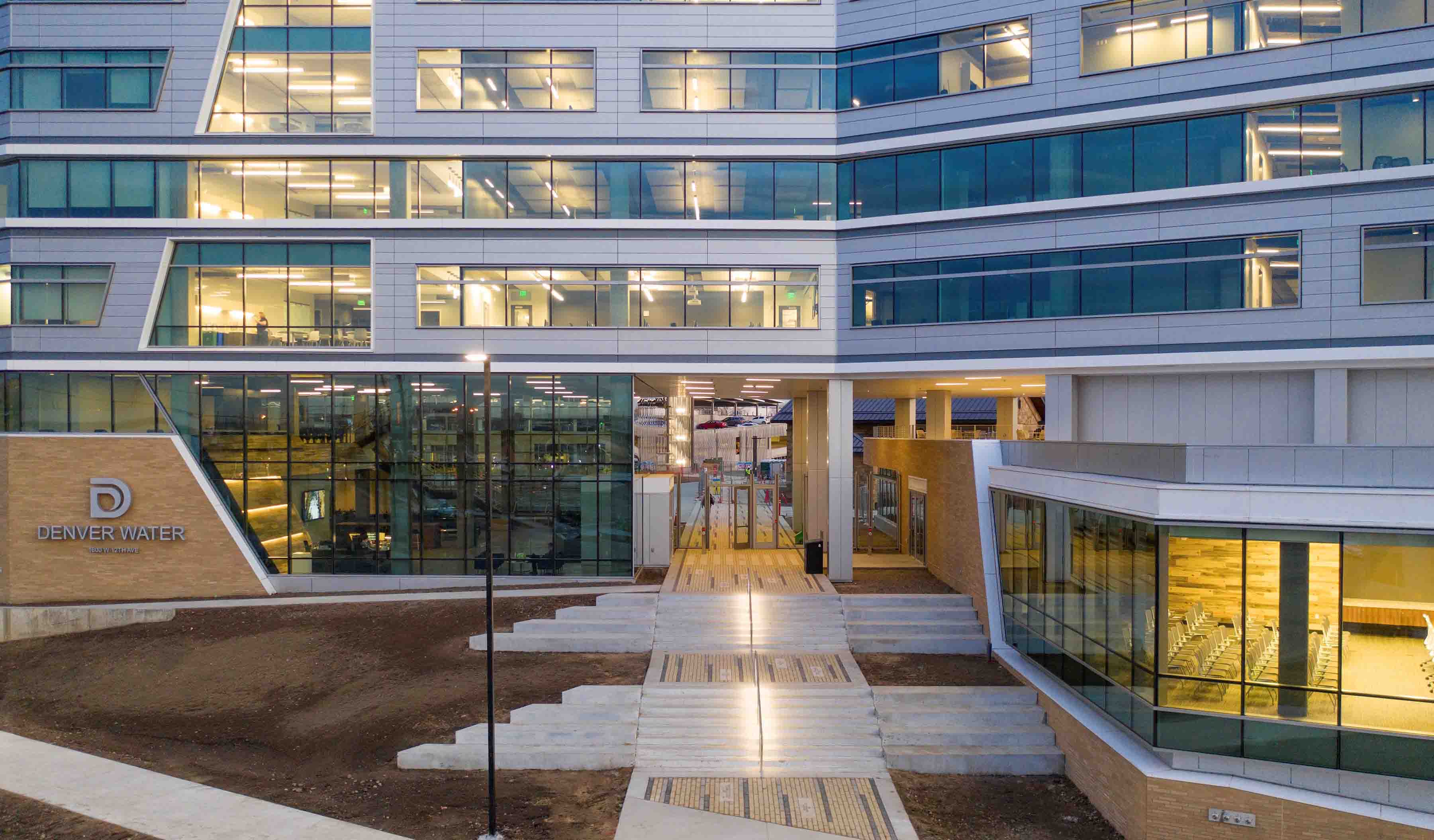

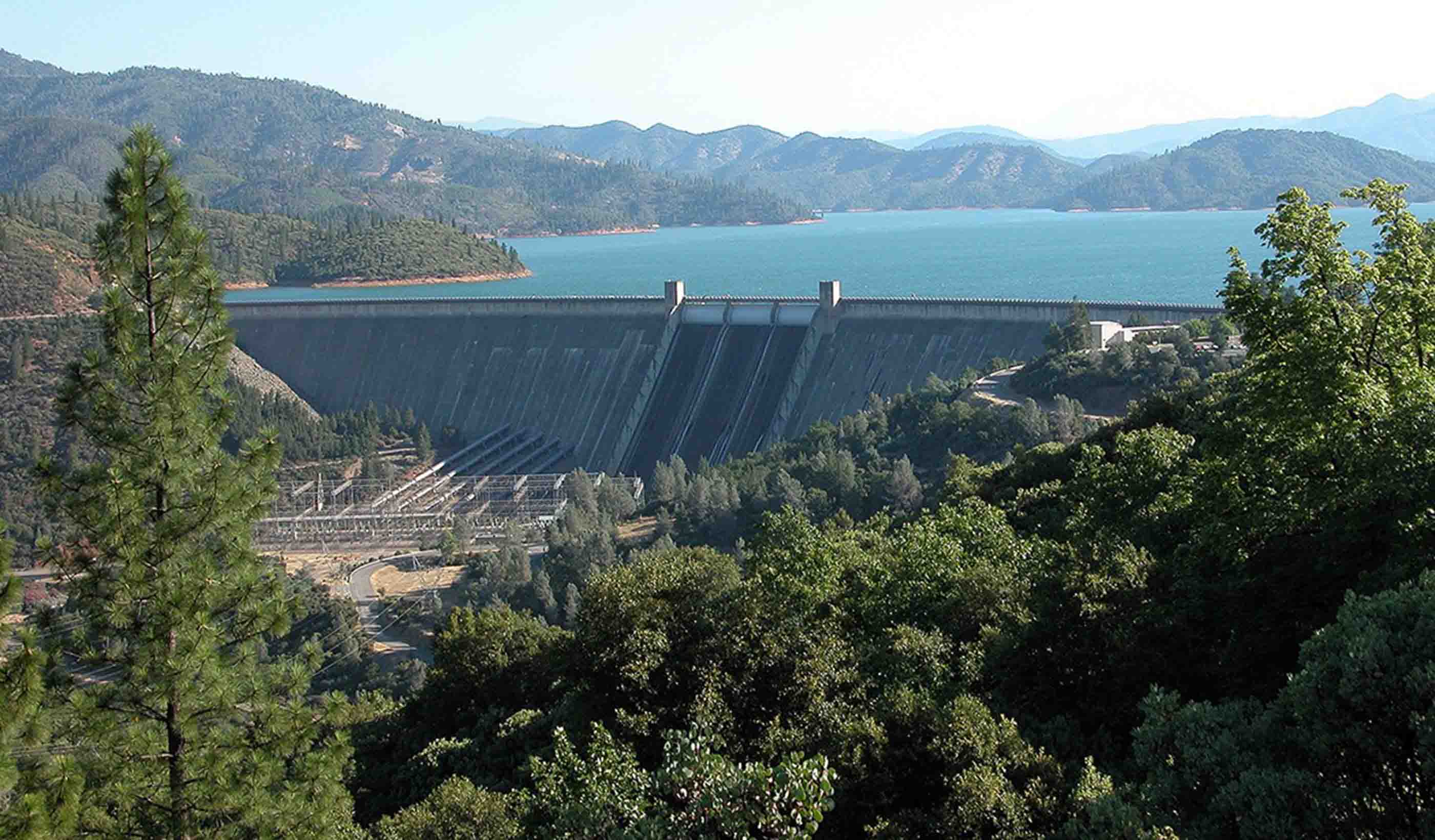

Published Article Denver Water increasing height of Gross Reservoir Dam

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: Advanced Tech and Reality Insight

-

Published Article Franklin Expedition shipwrecks in the Arctic face a new threat—melting ice

-

Blog Post Could ‘smart’ building facades heat and cool buildings?

-

Published Article Towering transformation: Yale revamp of historic structure embraces green design

-

Blog Post Sustainable mining finances: Exploring costs and liabilities

-

Blog Post What is a comprehensive plan? 6 steps to help your city

-

Published Article Sense of Community: Culturally responsive design fits buildings to place and purpose

-

Video Behind the Scenes: Designing for Career and Technical Education

-

Blog Post Geoexchange system installation: 6 steps that prioritize safety and efficiency

-

Published Article What’s the deal with efficiency?

-

Webinar Recording Prepare for the Unexpected: Don’t let a flood put you under water

-

Publication Inside SCOPE at COP28

-

Blog Post The next destination: Passive design airports

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The Growth and Innovation Episode

-

Blog Post How do we secure the water supply needed for hydrogen production?

-

Video Raising dams to provide water security

-

Blog Post Why decarbonizing hospitals smartly is better than electrification for healthcare design

-

Video Bringing a safe, reliable drinking water system back to Jackson, Mississippi

-

Blog Post Stream restoration requires working the bugs into your project

-

Blog Post Shrinking space: Post-pandemic law firm offices are smaller and more communal

-

Blog Post How green stormwater infrastructure can help cities manage intense rainfall events

-

Blog Post Building decarbonization strategy: It starts before electrification

-

Published Article Is your smart building an easy target for hackers?

-

Published Article Pumped storage in the USA: A story of IPPs, PPAs, and regulated utilities

-

Published Article The devastation of debris flows and the difficulty of predicting them

-

Published Article Optimizing complex HDD design and overcoming subsurface challenges

-

Blog Post Stantec’s Top 10 Ideas from 2023

-

Published Article Public agencies test digital twin tool for improved asset monitoring

-

Blog Post 3 steps to achieve One Water in the real world

-

Blog Post Does your building need a life cycle assessment?

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The Rail Episode

-

Report Showcasing success with Nature-based Solutions at COP28

-

Published Article The high stakes game

-

Published Article Stantec on mining’s quest for healthy closure

-

Blog Post Pumped storage hydropower and the Inflation Reduction Act are a renewable powerhouse

-

Published Article Sounding off on open office plans and workplace acoustics

-

Blog Post Low-carbon building materials: Designers discuss alternative options

-

Video How investing in downtowns fosters community and economic growth

-

Published Article Pumped storage hydropower: Helping to drive the energy transition

-

Published Article Turquoise hydrogen producers could capture flourishing graphite market

-

Blog Post Dam removal: An engineer returns to restore a Connecticut river of his childhood

-

White Paper Adapting flood prediction for the climate crisis era

-

Publication Design Quarterly Issue 20 | RETHINK

-

Blog Post 5 questions to ask before you write a decarbonization RFP

-

Published Article Applying the 3Rs to mine ventilation

-

Report Catalyzing Calgary’s Downtown West

-

Published Article Protecting cultural artifacts: Archaeology’s role in building projects

-

Webinar Recording Design and development of large diameter water tunnels

-

Blog Post Mining decarbonization is key to creating clean energy

-

Blog Post New ASHRAE standards tip the balance toward net zero buildings

-

Webinar Recording Run your models faster and get results

-

Published Article Got yourself a deal? M&A lessons from Stantec

-

Video Restoring the coastal resilience of a unique Great Lakes ecosystem

-

Published Article Financing boom supercharges Superfund

-

Published Article Designing for school safety through CPTED and biophilic concepts

-

Video Miami design team sets the table for success

-

Webinar Recording Mall of the Future Webinar Series

-

Blog Post How to create a lead service line inventory through data

-

Video Helping meet tomorrow’s water needs in Colorado

-

Published Article Hydraulic modeling approaches in drainage design and water resources engineering

-

Published Article Don’t 'debug' the selenium treatment system

-

Blog Post How does the 2020 National Building Code impact seismic design in Canada?

-

Podcast Talking Transit-Oriented Development with Sisto Martello

-

Video The Meaning of Design

-

Blog Post 4 questions a wastewater utility should ask before expanding

-

Blog Post Mobility hubs are the key to unlocking corridor development potential

-

Blog Post Dam safety: How technology can help dam owners and operators overcome 3 challenges

-

Blog Post What role do we play in decarbonization?

-

Blog Post Carbon capture methods: How can we capture and remove carbon from our atmosphere?

-

Blog Post 100% renewable energy: Making that commitment count

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The Dam Episode

-

Published Article Sustainably and quickly getting critical minerals to market

-

Blog Post So, you’ve captured carbon effectively. Now what?

-

Blog Post Embodied carbon: Mining to decarbonize buildings

-

Blog Post Reusing water while capturing carbon

-

Published Article Confidence in conveyance

-

Published Article Precast, prestressed concrete I-beams for the Red-Purple Modernization Program

-

Video What is Stantec.io?

-

Podcast Scientists discover dinosaur ‘coliseum’ in Alaska’s Denali National Park

-

Technical Paper Post-wildfire debris flow and large woody debris transport modeling

-

Technical Paper Advancing debris flow hazard and risk assessments with modeling and rainfall intensity data

-

Published Article Communicating the difference between hazard and risk

-

Technical Paper What does landslide triggering rainfall mean?

-

Webinar Recording Mineral processing through a sustainability lens

-

Technical Paper Debris flow hazard mapping along linear infrastructure: An agent based mode and GIS approach

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: Extreme Weather and Digital Solutions

-

Published Article Floating offshore wind power could be the key to reaching decarbonization targets

-

Blog Post ESG programs that focus on health help build climate resilience, create financial benefits

-

Webinar Recording New US federal incentives will drive wastewater renewables

-

Video Helping create the most sustainable tree nursery business park in Europe

-

Blog Post How do you create thriving, connected places? 5 ways to expand transit-oriented planning

-

Video The costs behind PFAS treatment for drinking water

-

Blog Post The future of design and AI in architecture

-

Video Workplace Reboot: A workspace that reflects a commitment to sustainability, health, and well-being

-

Blog Post Robots in the workplace: This one scans for indoor air quality and more

-

Webinar Recording Optimizing blended water sources to prevent metal corrosion

-

Published Article Nature-based solutions: Crucial innovations for a resilient, sustainable future

-

Blog Post Solving for H: 4 challenges hydrogen experts are working to resolve

-

Design Quarterly Issue 19 | Decarbonization

-

Published Article Destination Maintenance

-

Published Article Developments in custody transfer metering of natural gas

-

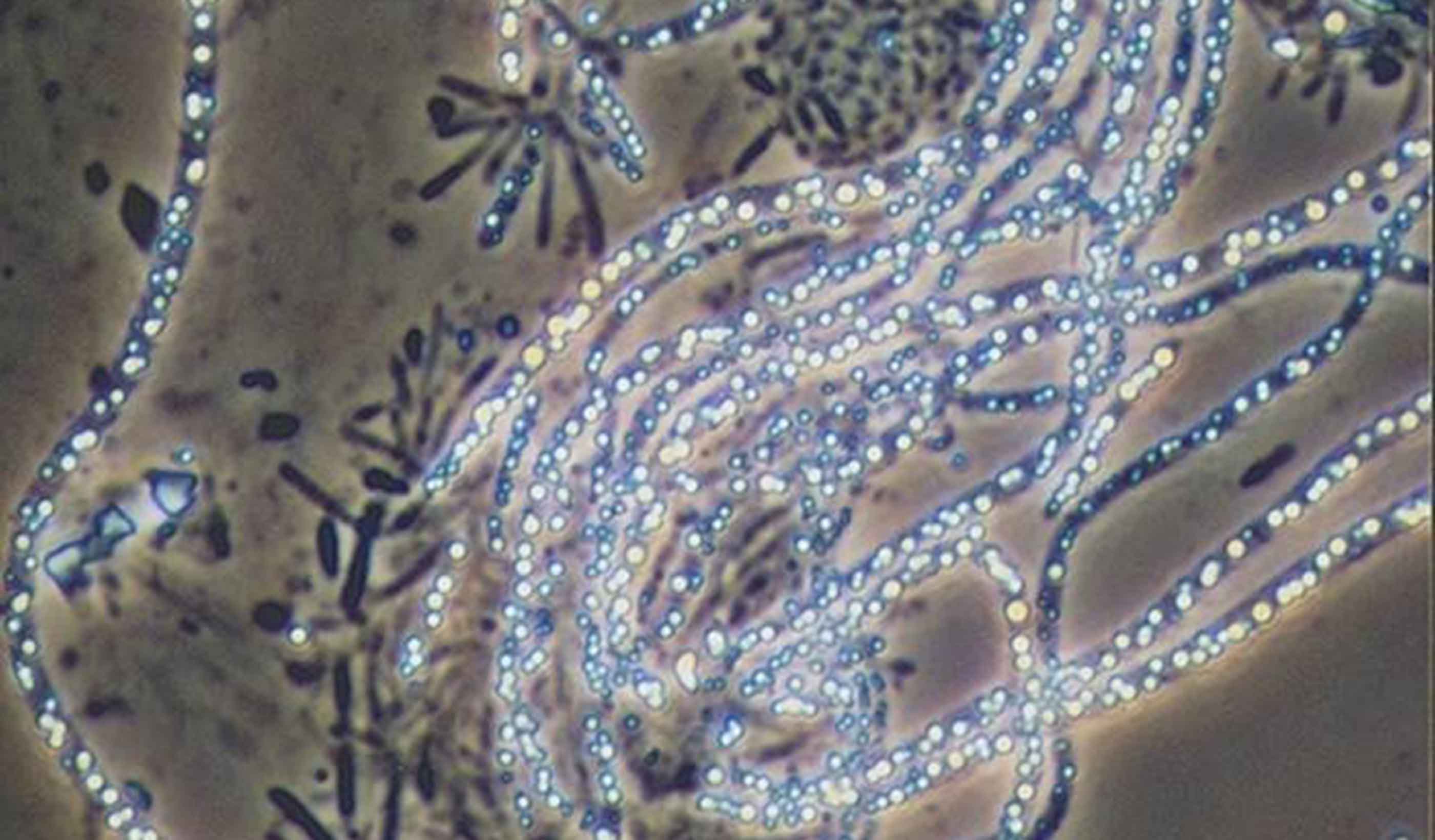

Technical Paper Blind spots in CyanoHAB monitoring

-

Video Mitigating flooding impacts through stream restoration

-

Video A better way to move people and goods at airports? Autonomous vehicles

-

Video How can design better prepare future healthcare professionals?

-

Blog Post Advanced manufacturing facilities are key to a sustainable future

-

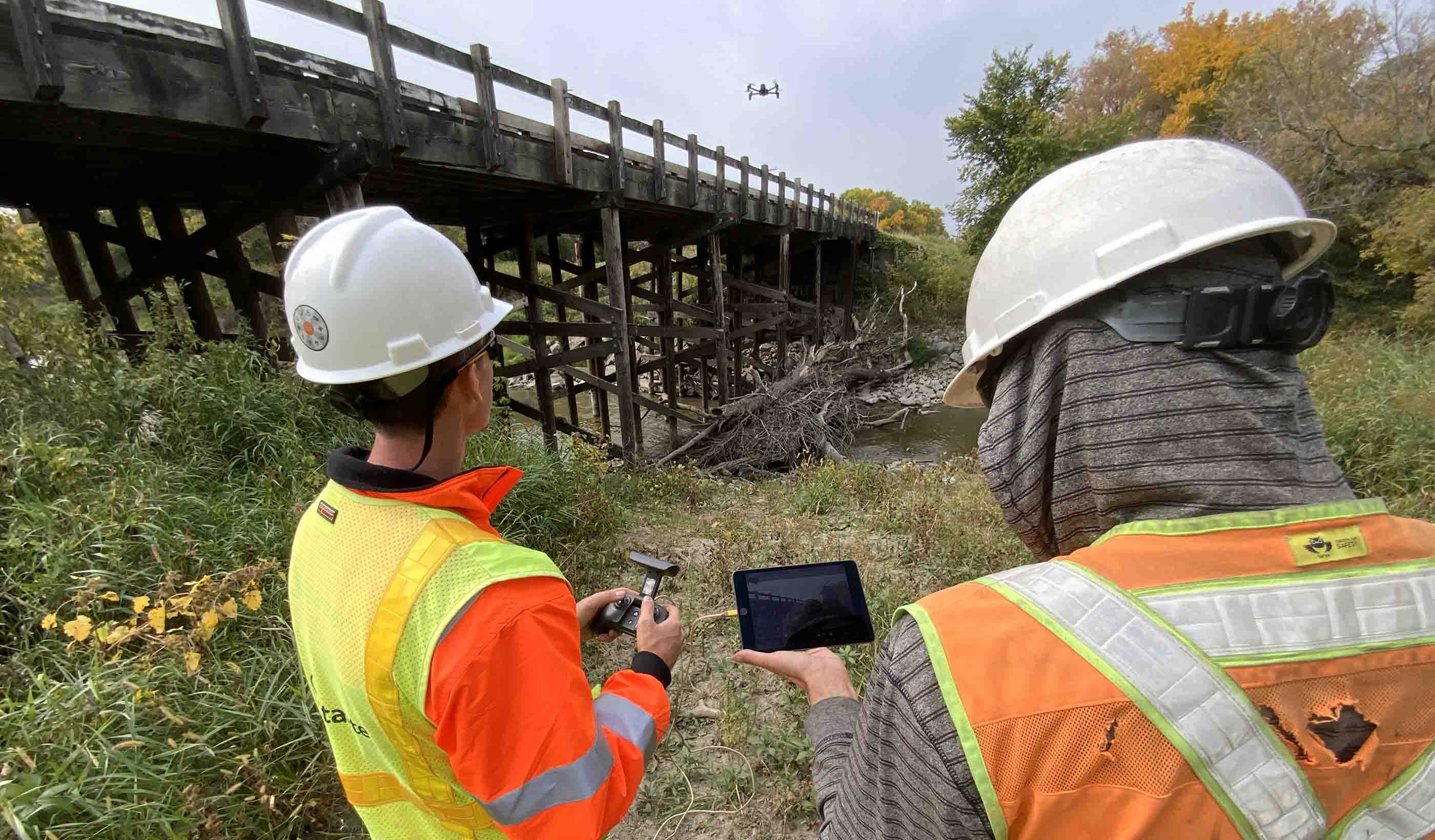

Video How drones are making bridge inspections safer and more efficient

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: Stantec Beacon™

-

Published Article Canadian funding to advance mining’s ESG projects

-

Blog Post Stream restoration is critical for mine reclamation

-

Technical Paper Supporting healthier and more resilient communities through investments in mobility

-

Webinar Recording Potable reuse: Achieving water sustainability in a changing climate

-

Webinar Recording Be prepared for the unexpected

-

Published Article Turning tailings waste into value

-

Blog Post Trauma-informed care: Indigenous healthcare designed for empathy, wellness, and safety

-

Published Article Integrated digital approach to managing geohazard risk

-

Published Article Analysis: Complexity and controversy cloud US permitting reform

-

Published Article Detecting leaks using remote sensing pipeline monitoring

-

Published Article Master planning in an age of turbulent change

-

Blog Post Bats in buildings: How airborne eDNA can help you identify bat species at risk

-

Video Stantec Beacon™ and Travers (the largest solar facility in Canada)

-

Published Article Multi-pronged trenchless rehab approach

-

Blog Post Zero emissions buses and the energy transition: How do transit agencies adjust facilities?

-

Video Implementing AV Applications at Airports

-

Webinar Recording Get ahead of FEMA’s Future of Flood Risk Data Initiative

-

Blog Post How water utilities can develop a digital twin and use GIS mapping to meet future needs

-

Published Article Time for transformative thinking in western water

-

Video How to repeatedly save your client time and money with Stantec Beacon

-

Published Article Elevating community mental health

-

Published Article From A to Gen Z: Designing better workspaces for everyone

-

Report Real-world Examples of Biological Monitoring with Environmental DNA (eDNA)

-

Published Article Consultant Q&A: Stantec's Firas Al-Tahan on Evolution of Mobility, Design-Build

-

Blog Post 8 challenges holding back vertical farming facilities

-

Published Article Net zero potash mining

-

Webinar Recording The 2023 proposed revisions to the steam electric ELGs are out – now what?

-

Published Article Crews cut and roughen Colorado dam for $531M raise project

-

Video Improving transit safety and efficiency with the innovative Yard Control System

-

Video Retrofitting Hammond, IN’s downtown core from car-centric to a walkable neighborhood

-

Blog Post Don’t let construction ground your airport: 5 ways to manage traffic disruptions

-

Blog Post From microchips to canola oil, manufacturers want to build factories in North America

-

Blog Post A modular construction solution to the mental healthcare crisis

-

Blog Post Can emerging alternative delivery processes result in better hospital design?

-

Published Article Assessing, remediating and performance monitoring abandoned mine sites

-

Blog Post 3 steps to fully accessible and barrier-free transit

-

Blog Post 3 ways municipalities can use agile financial planning to prepare for unexpected events

-

Blog Post How is California tackling water sustainability with data? What does it mean elsewhere?

-

Blog Post Healthy roots: How to create educational spaces for early developmental success

-

Video Workplace Reboot: 4 ways buildings and property owners can decrease potential legislation penalties

-

Webinar Recording Impacts of the new PFAS Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCL) and what you can do

-

Video Keeping communities connected through a modern bridge replacement

-

Published Article Drought management lessons from around the globe

-

Video Our underwater archaeology team explores Canada’s past

-

Published Article Wareham Dam interim spillway repairs

-

Published Article Paging all future veterinarians

-

Blog Post Fish passage: Fixing culverts is key to better stream habitat for salmon, other species

-

Published Article Emerging trend: Wind turbines paired with energy storage

-

Webinar Recording Design and operation of chloraminated water systems

-

Design Quarterly Issue 18 | The Future of Design

-

Video What’s so great about integrated design?

-

Published Article How the latest technology makes better buildings

-

Blog Post Proton therapy design (Part 2): Tracing the patient journey

-

Blog Post Water affordability with WARi®: How can utilities help their most vulnerable customers?

-

Published Article Evolving roles of the workplace designer

-

Blog Post How design can support mental health through crisis stabilization centers

-

Blog Post VR and community outreach programs: Building social acceptance with immersive technology

-

Published Article How does innovation in mining accelerate ESG goals?

-

Blog Post New York City’s Local Law 97 is fighting climate change, focusing on sustainable buildings

-

Blog Post PFAS in Canadian provinces: Where are the regulations?

-

Published Article Required: Clean Mine Power Solutions

-

Blog Post 6 design approaches that humanize cancer care amid technology advances

-

Published Article How to curb skepticism around Nature-based Solutions

-

Blog Post Across ever-changing landscapes, technology keeps our pipelines safe from geohazards

-

Published Article The right ingredients for tailings management

-

Blog Post Designing for neurodiversity: Creating spaces that are inclusive of all

-

Blog Post How can machine learning help water utilities find lead service lines?

-

Blog Post Finding funding: New opportunities abound for the mining industry

-

Webinar Learn strategies to guide our communities in unlocking new urban opportunities

-

Blog Post Successful Indigenous school design: Listening, understanding, and acting

-

Video Growing native plants for better ecosystem restoration projects

-

Video Workplace Reboot: Understand the penalties for not complying with emissions legislation

-

Blog Post How can schools build strong career and technical education programs? Partnerships

-

Video Collaborating with communities to create stormwater solutions

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The Soil Risk Map Episode

-

Blog Post What is an innovation center? A collaborative workspace that’s essential in today’s office

-

Published Article Is your healthcare facility resilient enough?

-

Blog Post How prioritizing environmental justice in project planning can reduce discrimination

-

Blog Post Desalination: Leveraging the potential of seawater

-

Electrifying ferries can help us leverage crucial waterways while reducing emissions

-

Blog Post How does a mine site in the desert find water?

-

Blog Post Water and energy: A symbiotic relationship

-

Blog Post Water supply in the West

-

Blog Post Harnessing water to meet Canada’s renewable energy goals

-

Publication Research + Benchmarking Issue 03 | Planting Seeds

-

Blog Post Consider environmental due diligence as part of project planning—it can save time, money

-

Published Article Development, Environment, Community: A Q&A with Stantec President and CEO Gord Johnston

-

Published Article Navigating the Complexity of the Hybrid Workplace Design Process

-

Blog Post Savings without sacrifice: Value engineering can counter inflation on projects

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The Smart Cities Episode

-

Published Article Net Positive Energy for People

-

Published Article Creating Better Spaces

-

Blog Post 5 trends from CES that will majorly impact the built environment

-

Report One Water, One Future: A promising water pricing model for equity and financial resilience

-

![[With Video] New city regulations are driving building retrofits](/content/dam/stantec/images/projects/0127/the-westory-181249.jpg)

Blog Post [With Video] New city regulations are driving building retrofits

-

Published Article The Mighty Bus: Transit Hero of Our Growing Community

-

Blog Post Debunking 7 myths and embracing a universal design mindset

-

Podcast Design Hive: Robyn Whitwham on designing for mental health

-

Published Article Thinking Water: Challenges and opportunities of water management

-

Published Article A toilet in the middle of nowhere – with Derek Chinn

-

Expanding reservoirs to provide water security for communities

-

Published Article Net Zero: At the turning point

-

Published Article Tailings Management: A global concern

-

Published Article Challenges for the modernization of the Baygorria plant, Uruguay

-

Publication Design Quarterly Issue 17 | New Design Essentials

-

Published Article Mining EPCM Terms of Engagement

-

Blog Post Better than ever: 5 things becoming a parent taught me about pediatric design

-

Report Economic trends examined in Stantec Water’s new financial benchmarking report

-

Blog Post 7 ways we can design more resilient healthcare projects today

-

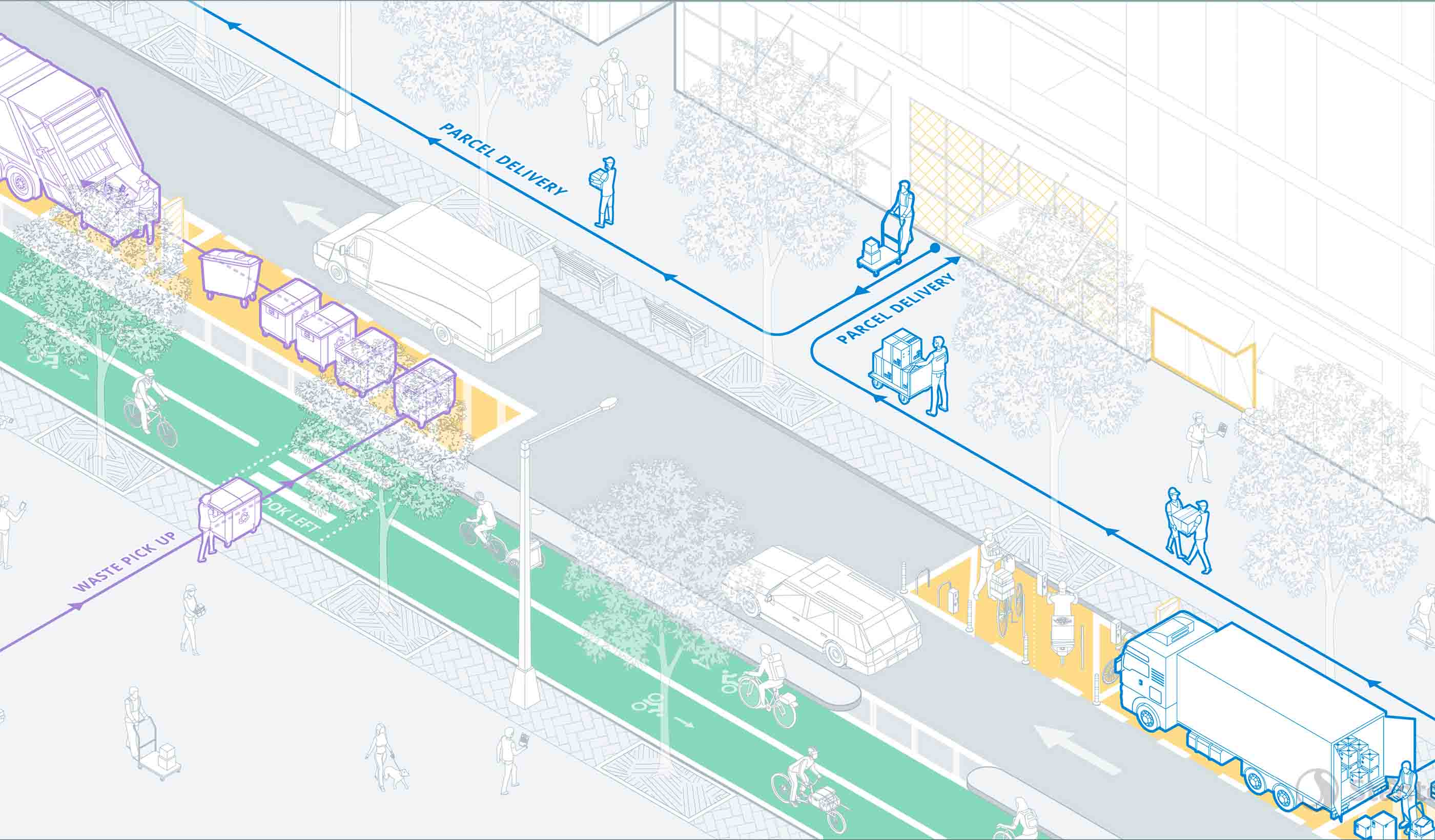

Report Delivering the Goods: Urban freight in the age of e-commerce

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The Digital Twin Episode

-

Published Article The challenges and opportunities of nature-based solutions

-

Blog Post Small modular reactors: How the next wave of nuclear power can fuel the energy transition

-

Video Workplace Reboot: How carbon impact legislation will affect building owners

-

Publication Inside SCOPE Issue 2: Week 2 at COP27

-

Blog Post When freshwater mussel surveys are needed, eDNA can show the way

-

Published Article Should interconnection participant funding be reformed or replaced?

-

Blog Post Bond programs 101: My school district needs money. Where do we start?

-

Blog Post Do you want functional lighting or fantastic lighting? The difference is commissioning

-

Publication Inside SCOPE Issue 1: Week 1 at COP27

-

Video Climate finance—leading change on an international scale

-

Report How data-informed mobility solutions create more equitable communities

-

Blog Post One module at a time: The future of affordable housing

-

Published Article Why healthcare masterplanning needs engineering masterminds

-

Blog Post 3 reasons why dam owners should prioritize adequate instrumentation and data

-

Published Article Water in a Warming World

-

Blog Post Envisioning the future of your healthcare network: How to develop a campus master plan

-

Blog Post Adapting our green spaces for a changing climate

-

Blog Post Using well-being, student input, and stewardship to design a WELL school

-

Published Article Pumped storage advocates see bright future due to new tax credits, reliability needs

-

Published Article Why mine operators should conduct energy audits

-

Webinar Recording Sustainable mine closure and rehabilitation, responsibly caring for land

-

Published Article Small scale hydroelectric power plants used to possibly solve California's energy crisis

-

Blog Post Family’s cancer journey helps designer turn fragile moments into better projects

-

Published Article The Kenaitze Indian Tribe welcomes a new education center in Alaska

-

Podcast Digital frontiers, reimagining science, engineering, and design

-

Published Article Up for the Challenge

-

Video Long Island Rail Road Third Track: expanding the busiest commuter line in the US

-

Published Article Pumped storage hydropower acts as a “water battery” that can sustainably power communities

-

Published Article US Offshore Wind Outlook

-

Video Cascading Climate Events and Predictions: Virtual Weather and Debris Flows

-

Video Building Decarbonization: The Urgency and Value

-

Video Cleaning Up the Mess: Quantifying Carbon Offsets with NbCS

-

Video It’s a Numbers Game: Using New Sensor Data to Achieve Climate Change Goals

-

Video Chasing Butterflies with our Eyes in the Sky

-

Video A Clear Lifesaver: Safeguarding water resources with Stantec’s WaterWatch

-

Video Managing our Largest and Most Valuable Public Asset: Our Roadways

-

Video Measurements With Merit: Evolving Data Collection to Enable Integrated Decision-making

-

Video Optimizing a Zero Cost Energy Future for the Water Industry

-

Video Operations of the Future: Using Artificial Intelligence to Run a Water Treatment Facility

-

Video The Benefits of Getting Your Head in the Cloud with FAMS

-

Video How We’re Using Machine Learning to Deliver Rapid Probabilistic Flood Predictions

-

Video Mapping the Route for a Zero-Emission Future

-

Video Buildings that Evolve: Design for Future-readiness

-

Video Digital Cities - Fire Flow

-

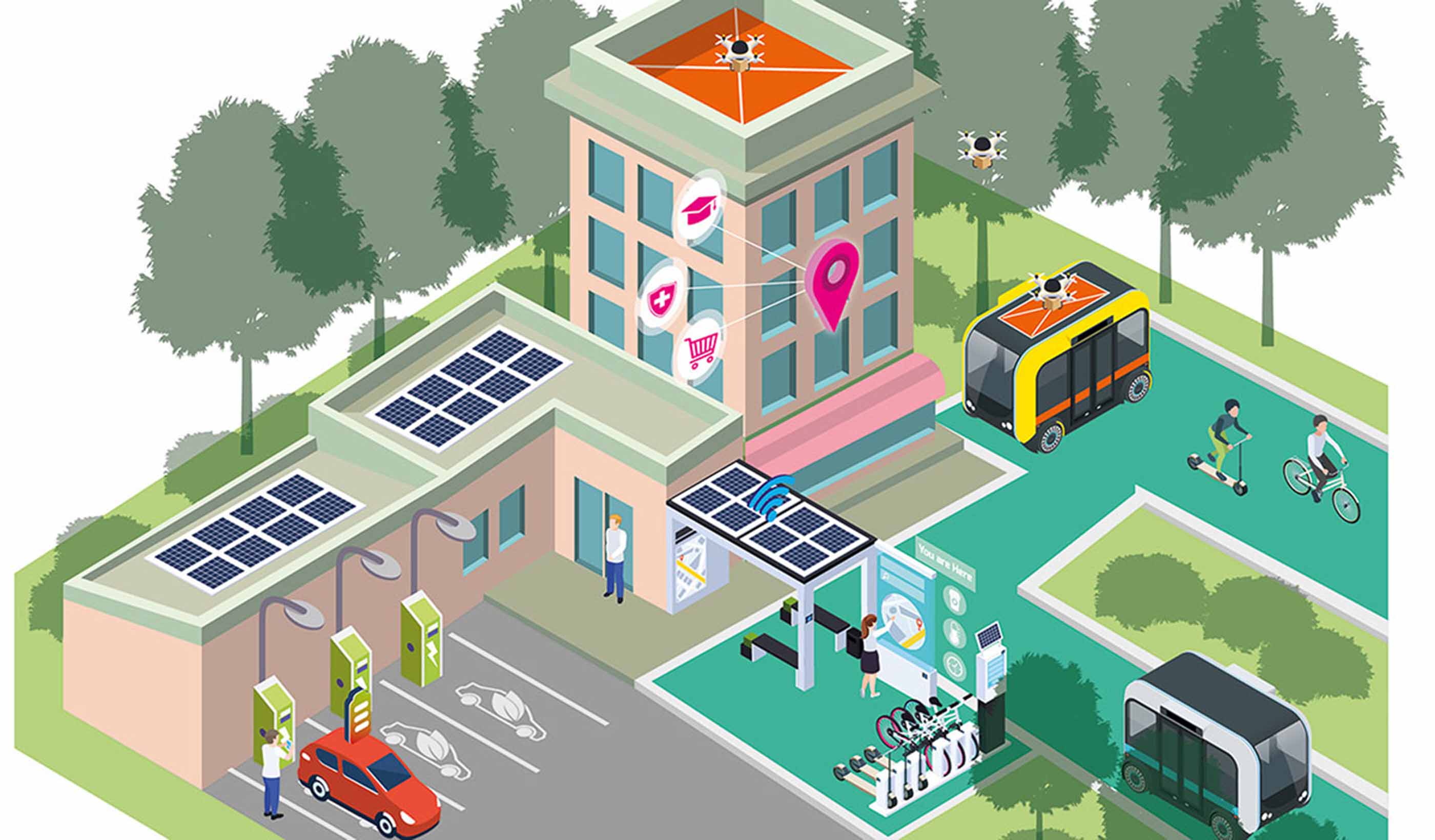

Video Planning a Smart City or Infrastructure? Don’t Start with Technology

-

Article Our guide to COP27

-

Blog Post Designing for a client’s nature-driven mission

-

Report Equity in Stormwater Investments

-

Published Article Regulation Roundup: How to manage excess soil through “the pause” in Ontario

-

Blog Post 6 things wastewater treatment plant owners need to know about PFAS

-

Blog Post It takes a village: Managing water in a time of climate change

-

Blog Post How can utilities prepare for the next big storm?

-

Blog Post All about energy resiliency: How different countries are adapting to extreme weather

-

Blog Post Supply and demand: Energy security in the UK

-

Published Article Mitigating the social impacts of mining projects

-

Blog Post 7 big ideas for revitalizing the urban realm

-

Podcast Design Hive: Daryl Fonslow on adaptive reuse to net zero

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The FAMS Episode

-

Blog Post How can technology protect against extreme weather events?

-

Video Coming together to restore a Colorado treasure – the Alamosa River

-

Published Article Plugging offshore wind power into our energy grid

-

Blog Post Eastern promise: The compelling case for green hydrogen in Atlantic Canada

-

Video Workplace Reboot: Building consensus - a key (and fun!) aspect of workplace strategy

-

Blog Post Measuring trees and tracking carbon sequestration from the sky

-

Video Stantec’s Buildings Team celebrates 10 years of being at the forefront of design

-

Published Article From necessity to amenity: changing the perception of storm water management

-

Blog Post Energy efficiency: The first step in decarbonizing a mine

-

Cleaner energy from waste

-

Blog Post Putting the people back in operations and maintenance facilities

-

Publication Design Quarterly Issue 16 | Climate Risk

-

Published Article UT Dallas Sciences Building Uses Zinc to Put Science on Display

-

Blog Post Gen Z water engineer: Climate change is the space race of my generation

-

Blog Post 5 steps companies can follow to change unused spaces into eye-popping pollinator habitat

-

Podcast Sustainability, Innovation and Failure to Launch

-

Webinar Recording Funding a resilient and carbon neutral water future

-

Published Article Woodlawn Cemetery could help solve mystery of Tampa’s erased Black cemeteries

-

Blog Post Rethinking air pressure in operating rooms could save lives

-

Technical Paper Simulation of some debris flows in Klanawa watershed in Vancouver, British Columbia

-

Video Workplace Reboot: A glass concourse transformed creates an urban, big city vibe

-

Published Article Brick-and-Mortar Retail Design: Reimagining the Way We Shop

-

Technical Paper A comparison of two runout programs for debris flow assessment at the Solalex-Anzeindaz region of Switzerland

-

Published Article Air Control

-

Blog Post Even popular retail malls are reevaluating and refocusing to amplify experiences

-

Published Article Increasing capacity and funding for rural communities

-

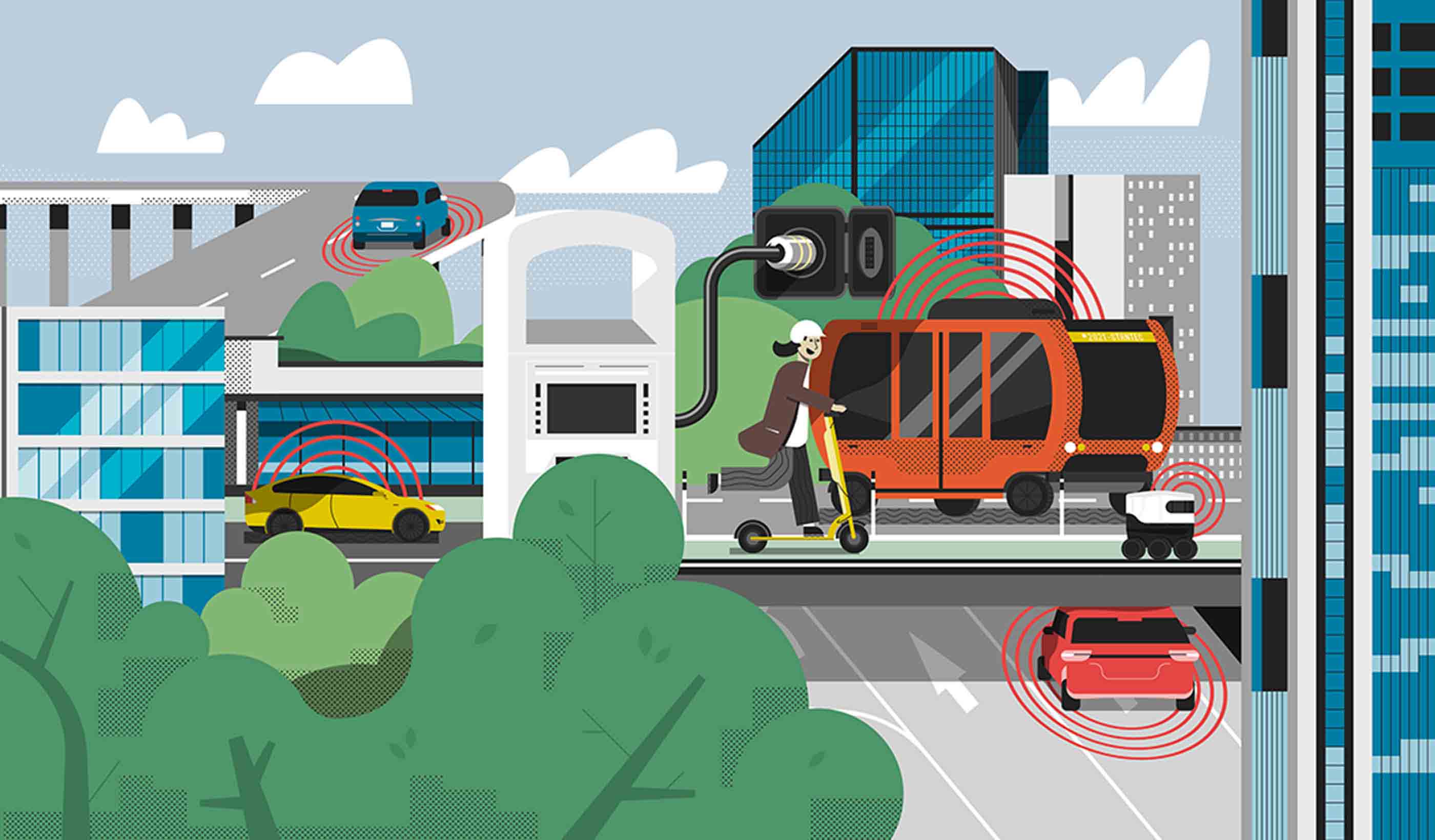

Published Article Building an electric vehicle program: Where should cities start?

-

Our approach: The Climate Solutions Wheel

-

![[With Video] 7 approaches to creating affordable housing for artists](/content/dam/stantec/images/projects/0111/pullman-artspace-lofts-185195.jpg)

Blog Post [With Video] 7 approaches to creating affordable housing for artists

-

Published Article How high-performance buildings attract high-performing people

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The CommunityHQ Episode

-

Technical Paper Improving Environmental DNA Sensitivity for Dreissenid Mussels

-

Technical Paper Detecting bat environmental DNA from water-filled road-ruts in upland forests

-

Published Article Texas Stages Development of Statewide Flood Plan

-

Blog Post Designing for gender inclusivity in industrial facilities

-

Technical Paper Evaluating environmental DNA metabarcoding as a survey tool for unionid mussel assessments

-

Video Constructing a new park and transportation corridor on Manhattan’s shore

-

Published Article Riding the Risks and Opportunities of ESG in Mining

-

Presentation Saltair study guides development in areas that may be subjected to natural hazards

-

Blog Post Artificial intelligence and machine learning can diffuse water’s ticking time bomb

-

Blog Post Rethinking resuscitation rooms: A new approach for a vital healthcare space

-

Technical Paper Lessons learned from the local calibration of a debris flow model and importance to a geohazard assessment

-

Technical Paper Informing zoning ordinance decision-making with the aid of probabilistic debris flow modeling

-

Blog Post How can businesses and policy makers achieve climate justice?

-

Design Hive: Dr. Rick Huijbregts on smart cities

-

Video A new spin on an old bridge type for safer travel across Kentucky’s Green River

-

Blog Post 4 challenges to overcome when transmitting offshore wind power

-

Published Article Sustainability by design

-

Published Article Stronger Together: Indigenous Peoples and Mining

-

Blog Post Freshwater mussels 101: Explaining the “aquatic archaeology” behind mussel relocation

-

Blog Post 5 reasons why your company should address greenhouse gas emissions

-

Blog Post 7 approaches to building reuse to help existing properties reach net zero

-

Video Workplace Reboot: The challenge – modernize, relocate, expand, sustain

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The EnviroExplore Episode

-

Video Home is Where the Art is

-

Published Article A new era of downtown opportunity

-

Blog Post Proton therapy design (Part 1): Putting the patient experience first

-

Blog Post 4 ways to make sure your connected-infrastructure technology program is … well, connected

-

Published Article Modeling Post-Wildfire Debris Flow Erosion for Hazard Assessment

-

Published Article Retail, Restaurant Industries Embrace Post-Pandemic Design Shifts

-

Technical Paper Environmental genomics applications for environmental management activities

-

Published Article Using Environmental DNA (eDNA) to Improve Biological Assessments

-

Blog Post Buildings that care: 6 things to know about WELL certification in hospitals

-

Published Article A trip through British Columbia in the life of a shipping container

-

Data + Design = Decision

-

Blog Post Are we finally about to achieve sustainable fusion energy?

-

Hydro batteries: Making renewables dispatchable

-

Blog Post What if simply restoring a closed mine site isn’t the best option?

-

Blog Post Can data improve dam safety?

-

How can solar canopies help us electrify our industry?

-

Blog Post What if the energy industry and environmentalists worked better together?

-

Blog Post For your next urban playground or revitalization, consider nature-based solutions

-

Blog Post Mapping your culture: How to help communities identify their heritage landmarks online

-

Blog Post A different West Side Story: How a boulevard changed Manhattan

-

Blog Post Breathe easier: Mitigating welding hazards with ventilation and exhaust

-

Blog Post Making smart asset choices from imperfect asset data

-

Blog Post Surveying Hawaii’s Kalaupapa Peninsula: Connecting a rich past to an exciting future

-

Blog Post Reflecting on Frederick Law Olmsted’s legacy for World Landscape Architecture Month

-

Blog Post The 4 pillars of ecosystem restoration work together to create better communities

-

![[With Video] 4 reasons we’re excited about our new automated design tool](/content/dam/stantec/images/ideas/blogs/021/audet-design-automation-graphic.jpg)

Blog Post [With Video] 4 reasons we’re excited about our new automated design tool

-

Blog Post How two scientists collaborated to develop a tool for better stream restoration design

-

Blog Post Urban highway removal: 4 ways to reknit a city’s fabric

-

Blog Post A new tool to protect marine environments from wastewater nutrients

-

Design Quarterly Issue 15 | Reuse and Revitalization

-

Blog Post Designing living systems to adapt to a changing climate

-

Video A channel runs through it: How we addressed the challenges of urban creek restoration

-

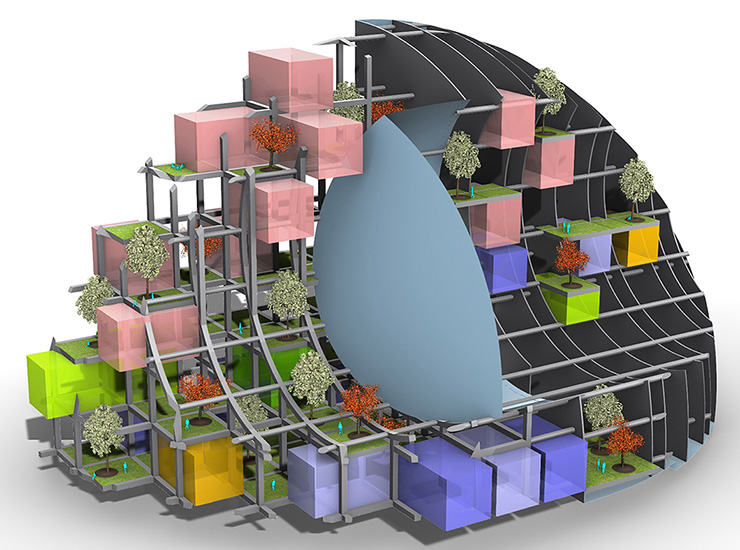

Blog Post Reinventing the Thompson Center: A research project into a modular, mixed-use destination

-

Published Article Deeper mines are tantalizing but costly

-

Blog Post Arc flash hazards: How engineering and standards can make for safer electricity use

-

Blog Post 3 design solutions to sort out the carbon impact of logistics

-

Blog Post Groundwater plays a critical role in climate change adaptation

-

Video Workplace Reboot: A reimagined office building becomes a magnet for both employers and employees

-

Blog Post Creating memories in a supportive home away from home

-

Blog Post Why we all need to care about mining

-

Blog Post Is your infrastructure facing climate risks? Here’s a tool to assess that

-

Podcast Stantec.io Podcast: The Fire Flow Episode

-

What does the future hold for autonomous vehicle policy and funding?

-

Blog Post Museum lighting case study: How a single exhibit embodies an impactful mission

-

Blog Post Smart resilience planning and design includes triple bottom line benefits

-

Published Article The future is now

-

Published Article Urban highway removal projects are on the rise across America

-

Published Article Santiago Airport becomes the most modern in South America

-

Blog Post Breaking the bias: How two women are making spaces and places more inclusive

-

Published Article How to Plan Office Space When Temporary Becomes Permanent

-

Published Article 4 HVAC Strategies to Still Protect Against COVID-19

-

Published Article A Guide to Workplace Metrics, Data, and Research

-

Blog Post Water reuse and river flows: What can we learn from the LA River?

-

Video Planning for the future of healthcare in Ontario

-

Blog Post The (remote) doctor is in: 5 ways telehealth is changing design

-

Blog Post Design through stories: Experience-based design in pediatric healthcare

-

Video Workplace Reboot: There's more to lighting design than meets the eye

-

Published Article Combining Generic/Flexible Labs with Highly Specialized Research Space

-

Article Stantec’s letter to the US Department of Transportation on its 2022-26 strategic plan

-

Blog Post Resilience checklist: 10 steps to improving your community’s resilience

-

Publication Research + Benchmarking Issue 02 | Connected

-

Webinar Recording Climate Solutions Webinar Series: Climate solutions that work

-

Published Article Water analytics data helping the rise of smart utilities

-

Blog Post The new low-carbon suburb: Retrofitting communities for success in the post-COVID era

-

Published Article It takes two: How architects and engineers blend their talents

-

Blog Post What is design automation, and how can you optimize it for your next project?

-

Webinar Recording Climate Solutions Webinar Series: Navigating climate change terminology

-

Video Workplace Reboot: Law firm takes the hybrid approach

-

Blog Post Railroad crossings: Involving locomotive engineers to better understand crash risks

-

Published Article 2021 Trenchless Q&A: A Look at Trenchless Engineering in Canada

-

Published Article Smarter care at Vaughan’s first hospital

-

Published Article St. Petersburg, Florida: Coastal Resiliency and Community Sustainability

-

Technical Paper Assessing the use of a SWA for treating oil spills in Canada’s freshwater environments

-

Report Quick and creative street projects

-

Video From airside to landside: Diversifying the airport program

-

Published Article The importance of the author-verifier relationship in project management

-

Podcast Design Hive: Brenda Bush-Moline on health equity

-

Technical Paper New research quantifies risk to bats at commercial wind facilities

-

Tailings Management, Meet Science Fiction

-

Published Article Screening and Framework Considerations for a PEL Approach

-

Webinar Recording Lateral structure jacking - how to install a railroad tunnel in a weekend

-

Report The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act: How Agencies Can Position for Funding

-

Blog Post We can build healthier streets by prioritizing the human experience

-

Webinar Recording What’s blowing your way? Proposed new odor guideline and monetary environmental penalties.

-

Blog Post 4 keys to keeping mechanical systems running during a hospital renovation

-

Published Article UV-C Radiation to combat healthcare associated infections

-

Blog Post 4 ways smart utilities improve water infrastructure

-

Video GlobeWatch: World Leading Remote Sensing Technology

-

Webinar Recording Ontario’s New Soil Regulation - Panel Discussion

-

Published Article Model builders

-

Blog Post Children’s play area design: How landscape architects set the stage for fun and games

-

Published Article Community-minded Design

-

Video For our US Audience: If We Built it Today – The Hoover Dam

-

Blog Post First Nations school design case study: Listen, learn, then design

-

Published Article Delivering pumped hydro storage in the UK after a three-decade interlude

-

Publication Inside SCOPE Issue 2: Week 2 at COP26

-

Blog Post EV is the bridge to transit’s AV revolution—and now is the time to start building it

-

Blog Post Managing the future: Why you should consider climate change risks on your next project

-

Publication Inside SCOPE Issue 1: Week 1 at COP26

-

Published Article No aspect of a mine will remain untouched

-

Blog Post A Smart(ER) approach to mobility: Prioritizing equity and resilience

-

Publication Design Quarterly Issue 14 | Tools and Data

-

Blog Post Student housing success: How P3 helped UC Davis meet its goals

-

Blog Post Brownfields, synchronized: Pros and cons of aligning development goals with remediation

-

Blog Post How is transit responding to reopening?

-

Published Article Hydropower: A Cost-Effective Source of Energy for Hydrogen Production

-

Blog Post Certainty in uncertainty: Machine learning can improve engineering decisions

-

Video Design inspiration for creating spaces to inspire your students, researchers, and staff

-

Published Article Deliver smart buildings using CSI Division 25, commissioning

-

Blog Post Does your company understand the risks of not transitioning to a low-carbon economy?

-

Blog Post Best places to produce hydrogen? Look at a topographic map

-

Blog Post Clean transport: Reducing carbon emissions on our roads

-

How do we power rural communities? By providing off-grid solutions

-

Blog Post Combating climate change across Australia

-

Blog Post Climate emergency: How governments around the globe are tackling the crisis

-

Published Article Vent tech shortage hits amid automation push

-

Webinar Recording Asset Integrity: Key considerations for blending hydrogen in your pipeline

-

Blog Post Mechanical engineering and industrial buildings: Why we need to go above and beyond

-

Blog Post Microtunneling 101: Good things come in small packages

-

Webinar Recording Demystifying Hydrogen Fueling for Transit Fleets

-

Blog Post Microtunneling: The next big thing

-

Video For our US Audience: Deadly Engineering - Power Plant Catastrophes

-

Blog Post What will the future campus look like?

-

Blog Post 3 emerging trends that put the “community” in community rec center design

-

Published Article Water Power

-

Blog Post Holistic heroes: How lighting designers use efficiency and modeling to boost performance

-

Blog Post Capturing carbon: How nature-based solutions help achieve net zero goals

-

Blog Post Tackling climate change: Identifying global opportunities in response to the IPCC AR6

-

Webinar Recording ESG, Net Zero Emissions and Climate Change Resilience for Manufacturing

-

Blog Post Protecting Florida homes from invasive plant species

-

Blog Post Continuous, holistic, and equitable health communities

-

Published Article Hydroelectric Dam Conversion with Diaphragm Walls, Retention Systems

-

Published Article Energy storage using conventional hydropower facilities

-

Webinar Recording What to consider when converting office or commercial space to science use

-

Blog Post To incentivise or to tax, or both? How we can reduce carbon in our infrastructure schemes

-

Blog Post Fully aware: How to track air pollutants and GHG emissions with near real-time data

-

Blog Post Elevating mobility infrastructure into a destination of its own

-

Published Article Top 100 Green Design Firms

-

Blog Post 5 things to know before starting an ITS deployment

-

Published Article Red Rock Hydroelectric Project: Successfully Generating New Power from a Pre-Existing Dam

-

All Hands on Deck: Building Strong Public Partnerships for Your Next Water Infrastructure Project

-

Published Article Storage tunnel will improve Narragansett Bay water quality

-

Published Article New bridge inspection techniques increase speed, efficiency, and safety

-

Blog Post 6 factors when planning a school sports facility

-

Published Article Back in Business: Minimizing Spread of Disease Remains Priority

-

Published Article Adapting to climate change in New York City

-

Blog Post Helping mines leverage the “S” in ESG

-

Blog Post The pandemic helped some utilities boost resiliency and delivery—while reducing risk

-

Published Article Everything’s bigger in Texas: How a P3 mega roadway project came to life

-

Published Article Environmental Technologies to Treat Selenium Pollution: Principles and Engineering

-

Blog Post Passports to a net zero carbon future

-

Published Article Life Extension and Savings through Field Testing and Engineering Analysis of a Draft Tube

-

Published Article Waste-to-energy tech could slash carbon emissions, but its promise remains underdeveloped

-

Published Article UAE Plans to Burn Mountains of Trash After China Stops Importing Waste

-

Published Article How to step into the net zero zone

-

Blog Post How New Orleans’ response to Hurricane Katrina improved public safety and economic growth

-

Blog Post Listening to the land to design an urban Indigenous healthcare facility

-

Blog Post Saving bats and generating more power: Acoustic data is the key

-

Report COVID-19 Recovery Strategies for Downtowns

-

Blog Post Following the flames: Preparing for landslides in wildfire country

-

Published Article Clean Slate

-

Blog Post Highlighting the hidden: Integrating operational infrastructure into the community

-

Published Article Graeme Masterton talks commuter systems, working from home

-

Blog Post What to consider when converting commercial or office space to life-science use

-

Published Article How Creative Designs Can Further a Vision of Sustainability and Resilience

-

Published Article Chimney Hollow Reservoir Construction Risk Management

-

Improving Dam Safety with Risk Informed Decision Making

-

Published Article Wellness in the Workplace: Burnout from the blurred lines of work and home

-

Published Article Airborne Electromagnetic Surveys: One More Tool in California’s Journey to Sustainable Groundwater Management

-

Published Article Can alternative tailings disposal become the norm in mining?

-

Publication Design Quarterly Issue 13 | After the Reset

-

Adapting to 21st Century Water Resource Challenges

-

Webinar Recording Sustainable mining: The future is now

-

Blog Post Harmonizing the seen and unseen when designing for neurodiversity

-

Published Article Building a new paradigm: commissioning in the 21st century

-

Blog Post The port of the future: Secure, sustainable, and welcoming

-

Blog Post Recycle your building: 8 reasons to consider adaptive reuse and retrofitting

-

Webinar Recording Designing with equity in mind: Rethinking how we approach projects

-

Blog Post Charged up: Key considerations around electric vehicle use on mine sites

-

Blog Post The potential of biogas in the energy transition

-

How can offshore wind power a more sustainable energy infrastructure?

-

What role should the energy industry play in a sustainable future?

-

Blog Post How can we reduce the carbon footprint of our oil and gas infrastructure?

-

Building partnerships for sustainable and resilient communities

-

Webinar Recording PFAS Investigations at Bulk Fuel Terminals and Refineries

-

Presentation Designing for Impact: Hubs and Corridors

-

Published Article Top Trends in Tailings Closure

-

The State of the Art in Selenium Management and Regulation

-

Published Article 3,300-foot lifelines: Remote runway construction takes grit, group effort

-

Webinar Recording How to spend COVID relief funding to improve K12 environments

-

Blog Post Wastewater case study: 10 years. 4 procurement methods. 1 cutting-edge treatment project.

-

Video Providing Transportation Lifelines for Central Hawke’s Bay

-

Blog Post Community spirit can strengthen collective resilience—and you can design for it

-

Video Creating a memorable passenger experience through art

-

Report What you need to know about the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds

-

Blog Post Plan B: Reasons to change your mining method from the obvious choice

-

Blog Post As we return to the workplace, it’s important to ask: How safe is your building’s water?

-

Report Planning a resilient future for defense communities

-

Published Article The rise of water risk

-

Blog Post Can we learn to share? How the sharing economy can help launch the mobility revolution

-

A New Way – Applying Asset Management to a Stormwater Program

-

Webinar Recording Climate Change & Resiliency Planning

-

Blog Post Stantec Institute for Applied Science, Technology: Fueling innovation for utility systems

-

Webinar Recording Integrating Affordability Into Capital and Financial Planning with WARi®

-

Blog Post Establishing clean water delivery is just the start: How to maintain investments long-term

-

Lead in Drinking Water. Is Plumbosolvency an issue in New Zealand?

-

Published Article Emerging Trends in Sports Facility Design

-

Blog Post From zero to hero: Kick-starting the rebirth of North America’s malls

-

Blog Post We can think differently to create more equitable outcomes in city building

-

Blog Post Supporting equity with an inclusive neighborhood—it’s urban planning for all

-

Published Article Elevators and Fire Sprinklers: Fire Safety Moves On Up

-

Video Ottawa CSST: A life on the water and a personal project

-

Blog Post Early education case study: Using design to nurture diverse learners

-

Report What do employees want in the office of the future? See what they told us.

-

Presentation Producing Hydrogen using Hydropower in the US

-

Webinar Recording Net Zero Emissions and Climate Change Resilience for Mining

-

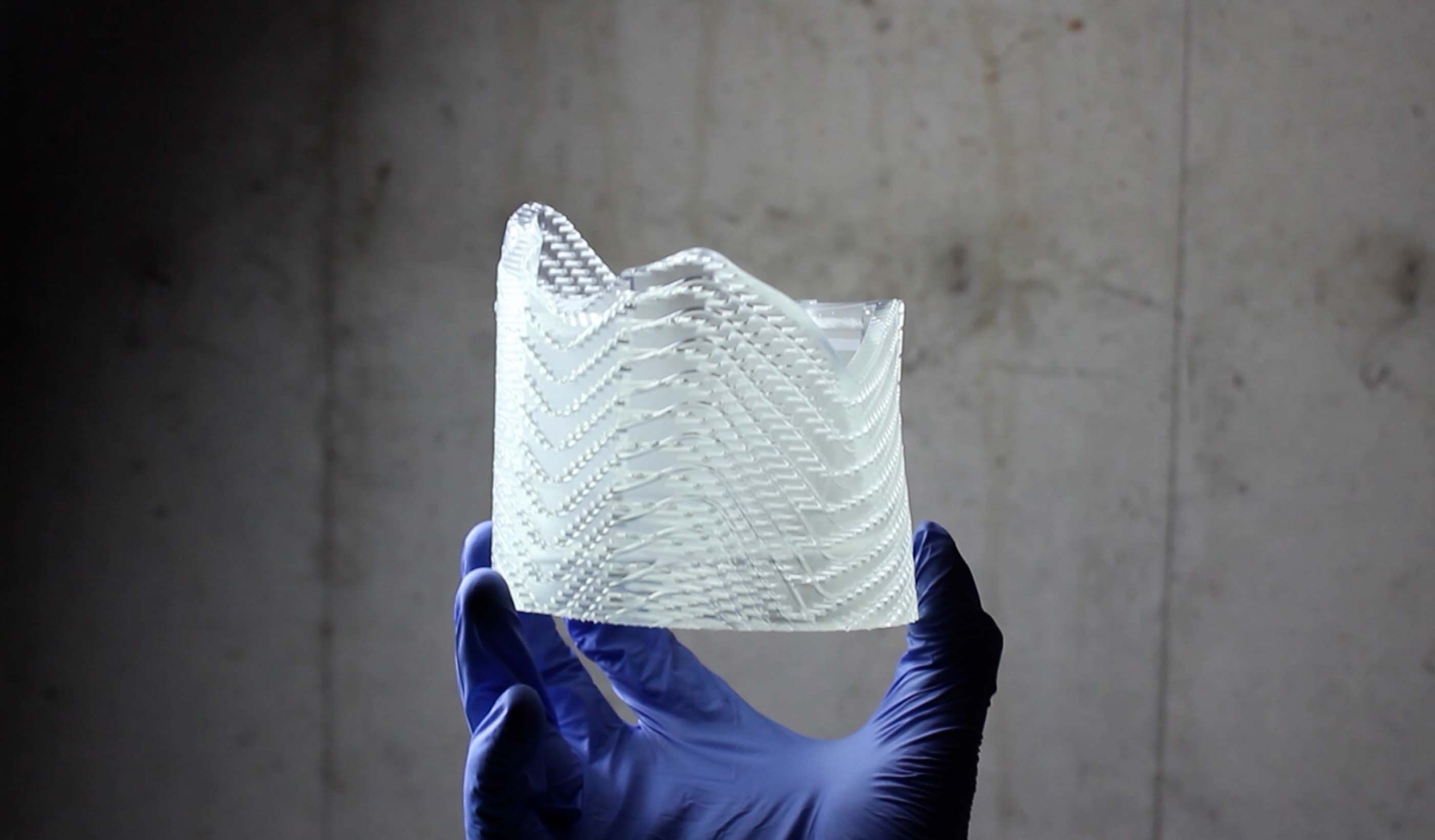

Video Exploring the possibilities with 3D printing

-

Blog Post 6 steps for effective modularization and preassembly planning

-

Blog Post How satellite image fusion and machine-learning can help us monitor large water bodies

-

Technical Paper A probabilistic model for assessing debris flow propagation at regional scale: a case study in Campania region, Italy

-

Publication Design Quarterly Issue 12 | Equity and Inclusion

-

White Paper What business are airports really in?

-

Published Article Living with Water in New Orleans

-

Blog Post COVID-19 has accelerated the need for flexible labs and research environments

-

Article Taking design to new heights through market insights and innovation

-

Technical Paper DebrisFlow Predictor: an agent-based runout program for shallow landslides

-

Published Article Office Design in a Post-Covid World

-

Blog Post 8 design strategies to enhance access to urban mental healthcare

-

Video Rolling out new mobility pilots

-

Video Making mobility work for people

-

Video Planning for the future of mobility

-

Blog Post The American Rescue Plan Act: 4 questions to get thinking about infrastructure projects

-

Webinar Recording PFAS and the Energy Industry

-

Blog Post A new digital tool can help predict landslides, protecting people and infrastructure

-

World Water Day: Valuing a finite, irreplaceable resource

-

Blog Post Beyond the terminals: How airports are helping strengthen communities and promote culture

-

Published Article Examining alternative project delivery

-

Don’t damn ageing dams

-

Published Article Iowa Dam Adds Hydroelectric Power Generation

-

Published Article Double-edged sword for industrial sector

-

Podcast We need an EV charging renaissance

-